Designing with the Mind in Mind

引言

用户界面设计规则 :从何而来?如何有效使用?

自从人们开始设计交互式计算机系统以来,有些人就试图通过发布用户界面设计指南(也称为设计规则)来推广良好的设计,包括这些早期的指南:

• Cheriton(1976 年)为早期的交互式(分时)计算机系统提出了用户界面设计指南。

• Norman(1983a,b)基于人类认知(包括认知错误),提出了软件用户界面的设计规则。

• Smith 和 Mosier(1986 年)撰写了最全面的一套用户界面设计指南。

•Shneiderman(1987年)在他的书《用户界面设计》的第一版以及所有后续版本中,都包含了“界面设计的八项黄金法则”。

•Brown (1988) 写了一本名为《Human–Computer Interface Design Guidelines》的设计指南书籍。

• Nielsen 和 Molich (1990) 提供了一套用于用户界面启发式评估的设计规则,Nielsen 和 Mack (1994) 对其进行了更新。

•Marcus (1992) 提出了在线文档和用户界面图形设计的指南。

近年来,在 21 世纪,发布了更多用户界面设计指南:

• 多位作者已撰写包含 UI/UX 设计指南的书籍:Stone 等人 (2005),Koyani 等人 (2006),Johnson (2007),Shneiderman 和 Plaisant (2009),以及 Rosenberg (2020)。

•一些组织已发布针对网络的可用性指南:W3C (2016),Yale 大学 (2020)。

•计算机公司已在其平台上发布桌面应用程序设计指南:Microsoft 公司 (2018),Apple 公司 (2020a)。

• 移动应用程序平台提供者也已发布指南,以帮助开发者创建更适用于移动设备的可用应用程序:Oracle 公司 (2017),Google (2019),Apple 公司 (2020b)。

用户界面设计准则的价值有多大?这就取决于将它们应用在设计问题上的人了。

用户界面设计与评估需要理解和经验

遵循用户界面设计准则不像遵循烹饪食谱那么按部就班。设计准则经常描述的是目标而不是操作。它们特意极其概括从而具有更广泛的适用性,但这也意味着,人们对它们准确的意义和在具体设计情境上的适用性经常会做出不同的诠释。

更进一步地,。在这种情况下,适用的设计规则经常冲突:它们建议不同的设计。这要求设计师确定哪个竞争的设计规则更适用于给定的情况并应优先考虑。

更复杂的是,往往会有多个规则似乎都适用于给定的设计情况。这时,这些设计准则经常会相互冲突,即指向不同的设计。这要求设计师确定哪个设计准则更适用于给定的环境,从而优先应用。

即使没有冲突的设计准则,设计问题也常常有多个冲突的目标——例如:

屏幕要明亮,且电池寿命长;

轻便且坚固;

功能多且容易学;

功能强大且系统简单;

分辨率高且加载快;

所见即所得(WYSIWYG),且盲人可用。

要满足这些计算机产品或服务的所有设计目标,通常需要权衡——大量的权衡。在相互冲突的设计准则间找到合适的平衡点需要进一步的权衡。

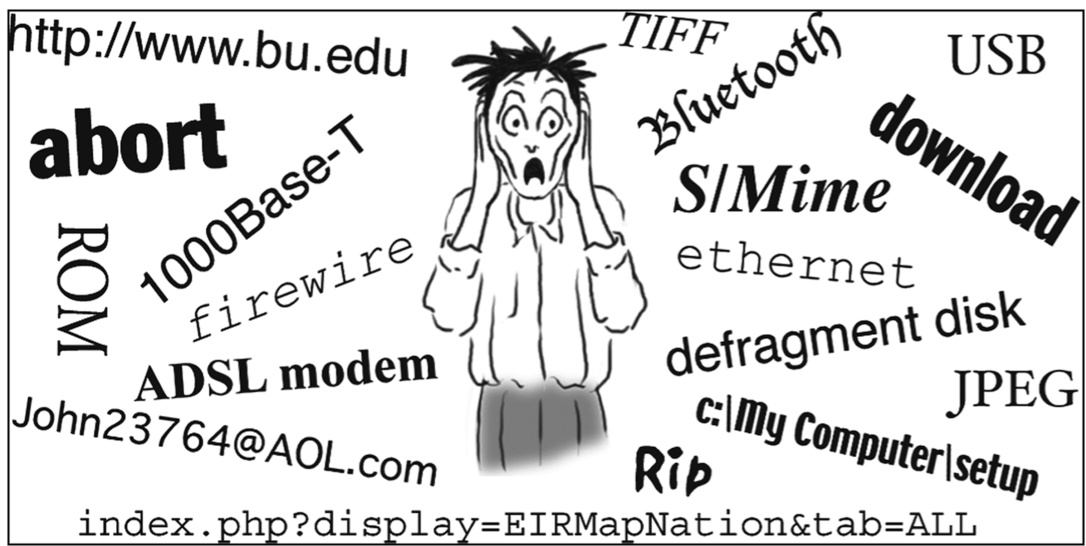

面对这些复杂情况,技艺娴熟的 UI 设计者或评估者必须更深思熟虑,而不是盲目地应用用户界面设计规则和准则。用户界面设计规则和准则更像法律,而不是生搬硬套的食谱。就像一套法律必须由精通法律的律师和法官来使用和诠释一样,一套用户界面设计准则最好由理解其基本原则并有过应用经验的人来使用和诠释。

遗憾的是,用户界面设计准则通常都是以设计布告的简单列表形式提供的,几乎没有提供任何理论依据或背景。当然有少数例外,比如 Norman(1983 a)。

再者,虽然很多早期用户界面设计和可用性的从业人员拥有认知心理学的知识背景,但大部分新参与的人并没有。这让他们很难理性地应用用户界面设计准则。提供这样的理论依据和背景正是本书的着眼点。

用户界面设计准则的比较

Comparing User-Interface Design Guidelines

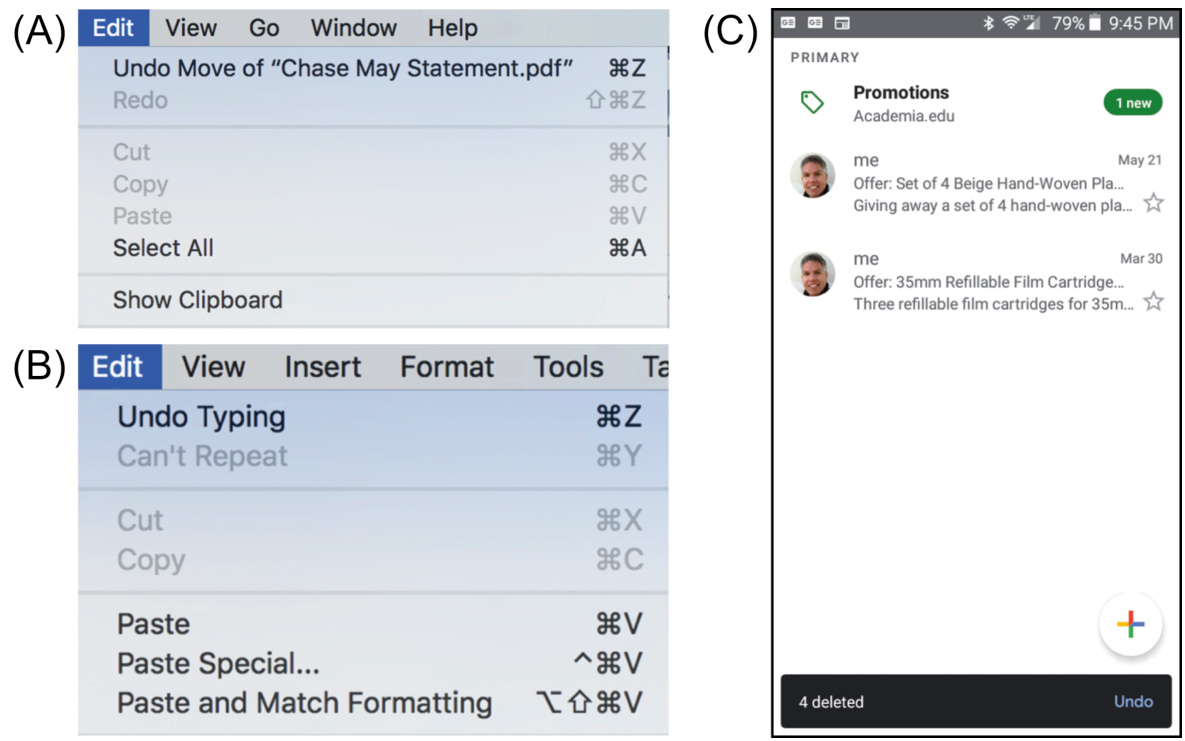

表 1.1 并排列出了两大最著名的用户界面设计准则,展示了它们包含的规则类型和相互间的比较(更多的准则可参考附录)。比如,二者的第一条规则都提倡设计的一致性,它们也都包含错误预防的规则。Nielsen-Molich 的规则“帮助用户识别、诊断错误,并从错误中恢复”接近于 Shneiderman-Plaisant 的规则“允许容易的操作反转”,而“用户的控制与自由”则对应“让用户觉得他们在掌控”。这种相似有其原因,而并不是因为后者受到了前者的影响。

表 1.1 两大最著名的用户界面设计准则

| 施耐德曼(1987 年);施耐德曼和普拉尚特(2009 年) | 尼尔森和莫利奇(1990 年) |

| 力求一致性 | 一致性和标准 |

| 服务于普遍可用性 | 系统状态的可见性 |

| 提供信息反馈 | 系统与现实世界的匹配 |

| 设计任务流程以获得完成感 | 用户控制和自由 |

| 防止错误 | 预防错误 |

| 允许轻松撤销操作 | 识别而非记忆 |

| 让用户感觉他们掌控着局面 | 使用灵活高效 |

| 减少短期记忆负担 | 美观简洁的设计 |

| 帮助用户识别、诊断和恢复错误 | |

| 提供在线文档和帮助 |

设计准则从何而来

对当前的讨论而言,这些设计准则的共性—它们的基础和起源,比每套设计准则的具体规则更重要。这些设计准则从何而来?它们的作者只是像时装设计师一样,试图将个人的设计品味强加在计算机和软件业上吗?

如果是这样,这些设计准则会因各自作者追求与众不同而变得非常不一样。实际上,忽略在措辞、强调点以及撰写时计算机技术状态的不同之后,所有这些用户界面设计准则是很相似的。这是为什么呢?

答案在于,所有设计准则都基于人类心理学:人们如何感知、学习、推理、记忆,以及把意图转换为行动。许多设计准则的作者至少有一些心理学背景,应用于计算机系统设计上。

例如,DonNorman 远在开始从事人机交互方面的写作之前,就已经是认知心理学领域的一名教授、研究者和多产作家了。Norman 早期的人机设计准则就基于他本人和其他人在人类认知方面的研究。他特别关注的是人们经常犯的认知性错误,以及计算机系统如何减少或消除这些错误造成的影响。

类似地,其他设计准则的作者,比如 Brown、Shneiderman、Nielsen 和 Molich,也都在应用感知和认知心理学的知识,尝试改进交互系统的设计,使其更具可用性和实用性。

说到底,用户界面设计准则是以人类心理学为基础的。

阅读本书,你将学到用户界面和可用性设计准则背后重要的心理学知识。

读者对象

这本书主要面向需要应用用户界面和交互设计指南的软件设计和开发专业人士。这包括交互设计师、用户界面设计师、用户体验设计师、平面设计师和硬件产品设计师。它还包括可用性测试员和评估员,他们在审查软件或分析观察到的使用问题时经常参考设计启发式方法。

第二个重要的受众是交互设计和人机交互专业的学生。事实上,这本书的第二版已成为大学水平 UI/UX 设计课程的流行教科书。因此,我在更新和完善这本书以制作第三版时,一个目标就是使其成为更好的教科书。

第三个预期的受众是希望了解用户界面设计规则的心理基础的软件开发经理,以便理解和评估他们所管理的人员的工作。

第一章:感知偏差

Chapter 1: Our Perception is Biased

摘要

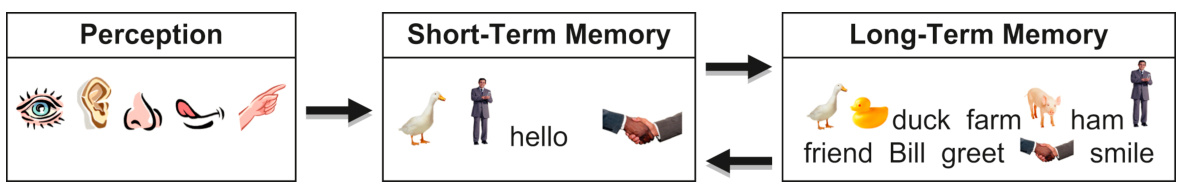

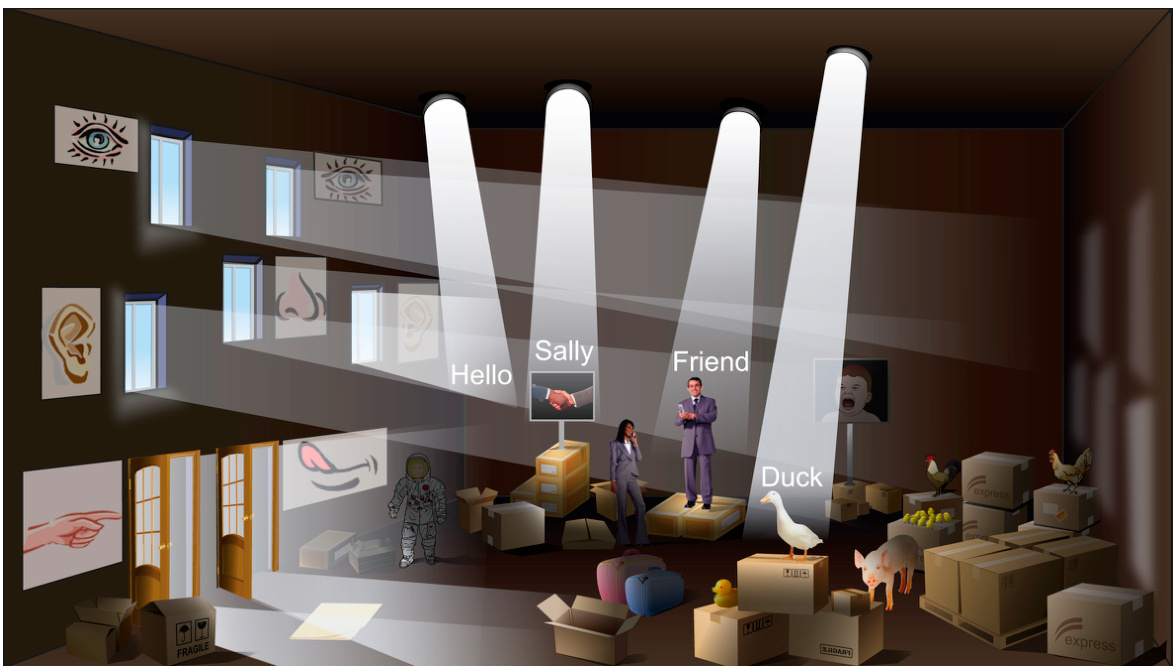

我们感知到的并非我们环境的准确反映。它至少受到三个因素的影响:过去的经验、当前的环境以及未来的目标。本章将详细讨论这些因素,举例说明它们如何影响感知,并解释它们对设计交互式系统的意义。

关键词

含糊不清;注意力瞬失;偏见;鸡尾酒会效应;环境;框架;目标;习惯化;麦克格鲁效应;缪勒-莱尔错觉;光学错觉;感知;启动效应

我们对周围世界的感知并非对实际情况的真实描绘。我们的感知受到至少三个因素的影响:

• 过去:我们的经验

• 现在:当前环境

• 未来:我们的目标

经验导致感知偏见

经验,即你过去的感知——可以在几种不同的方式上影响你当前的感知。

感知的启动

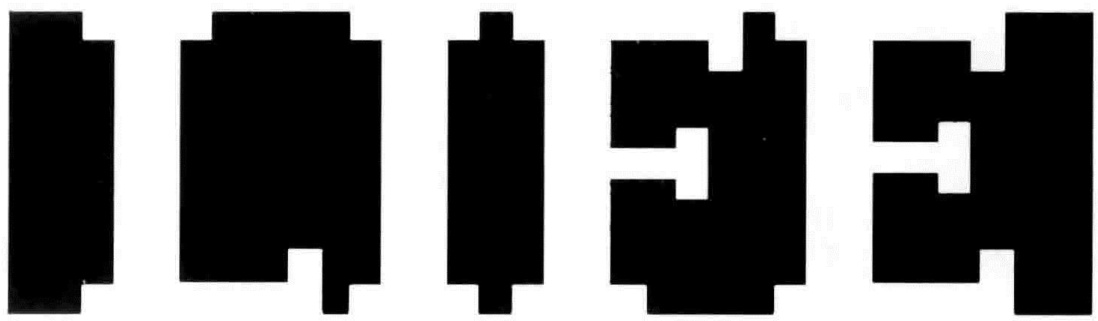

想象一下,你拥有一家大型保险公司,并将与一位房地产经理开会讨论公司新园区的建设方案。园区有五座建筑排成一排,后两座有给自助餐厅和健身中心采光的 T 字形庭院。如果房地产经理向你展示如图 1-1 所示的地图,你就会看到代表这些建筑物的五个图块。

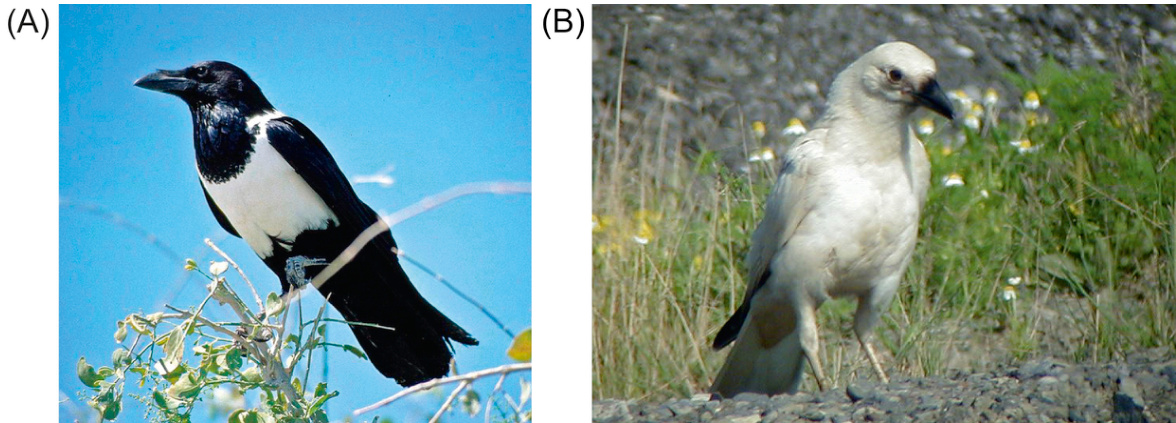

图 1-1 这是建筑地图还是单词?你看到的取决于别人告诉你看什么

现在想象一下与你见面的不是房地产经理,而是一位广告经理,讨论的是一个将在全国某些市场悬挂的广告牌。广告经理给你看的是同样的图像,但这次是广告牌的略图,由一个单词构成。这次,你清晰无误地看到了一个单词“LIFE”。

当感知系统预先准备看的是建筑物的形状时,你就看到了建筑物的形状,几乎察觉不到建筑物之间的白色区域。当感知系统预先准备去看文字时,你就看到了文字,也几乎注意不到字母间的黑色区域。

先入为主能够影响感知,有个著名的例子是一张素描。这张素描据传由R.C.James 所绘,大部分人对它的第一印象就是随手泼出的墨点。在继续阅读之前,先看看这张素描(见图 1-2)。

图 1.2 展示了先入为主在视觉上的效果。你看到了什么?

只有在告诉你这是一只在树附近嗅着地面的斑点狗之后,你的视觉系统才会把影像组织成一幅完整的画面。不仅如此,一旦你“看到了”这只狗,就很难再回头把这张素描看成随机无序的点。

以上是视觉的例子。经验也会影响其他类型的感知,如对语句的理解。例如,在不久前听说过疫苗污染事故的人与最近听说过利用疫苗成功对抗疾病的人,他们对“新疫苗含有狂犬病毒”这个标题或许就有不同的理解。

熟悉的感知模式或框架

我们生活中大部分时间都在熟悉的环境里度过:家中的房间、花园、上学放学上班下班经过的路线、我们的办公室、小区附近的公园、商店、餐馆等。不断置身的各种环境在我们心智中建立起模式,让我们对不同地方的东西有不同期待。研究者们把这些感知模式称为框架,包括在各个环境下通常遇到的对象和事件。

举个例子,你不需要时常详细检查每一个细节,因为对家里的房间足够熟悉。你知道它们的布局,也知道大多数东西放在什么地方。你或许都能够在全黑的情况下在家中行走。但你对家的经验要比自己的住宅更广泛。除了对自己住宅的了解,你的大脑对家也有一个广泛的模式认知。这个模式影响了你对所有家的认知,不论熟悉的还是陌生的。在厨房,你期待看到灶具和水槽。在浴室,你期待看到马桶、洗手池、淋浴器或者浴缸。

不同场合的心智框架影响人们在各个场合下对期待见到的事物的感知。因为不必不断地详细检视身边环境的每一个细节,这是心智的捷径,能帮助人们应付所处的世界。然而,心智框架也让人们看到其实并不存在的东西。

比如,如果你拜访一个厨房里没有灶具的房子,你事后可能会回忆看到过一个灶具,因为在你对厨房的心智框架里,灶具是厨房的一个重要部分。类似地,去餐馆吃饭的心智框架中一部分是付账单,所以你可能记得自己已经付过钱了而心不在焉直接就走出餐馆。你的大脑对后院、学校、城市街道、办公室、超市、牙医诊所、的士、空中交通等熟悉场合都有各自的心智框架。

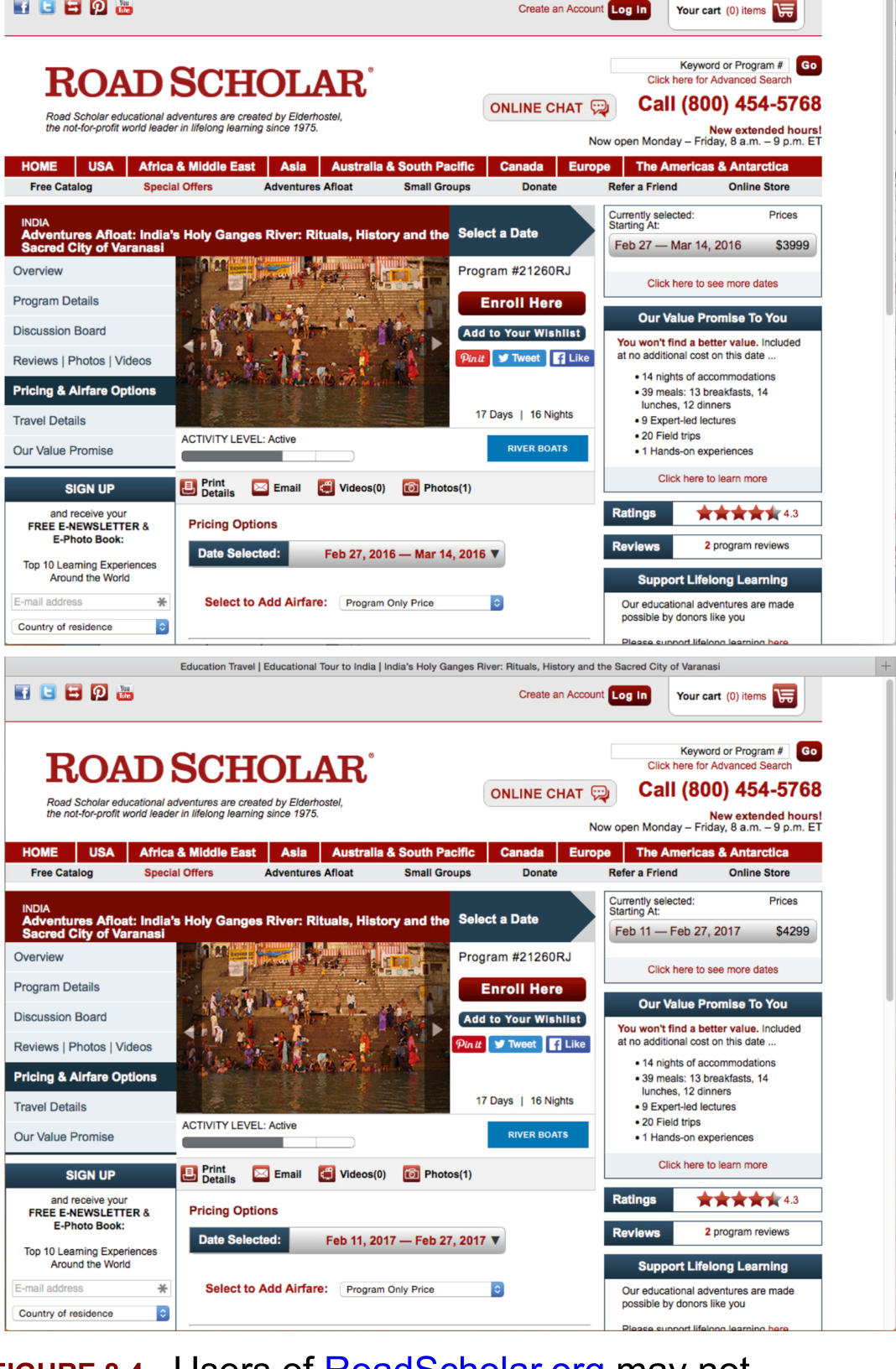

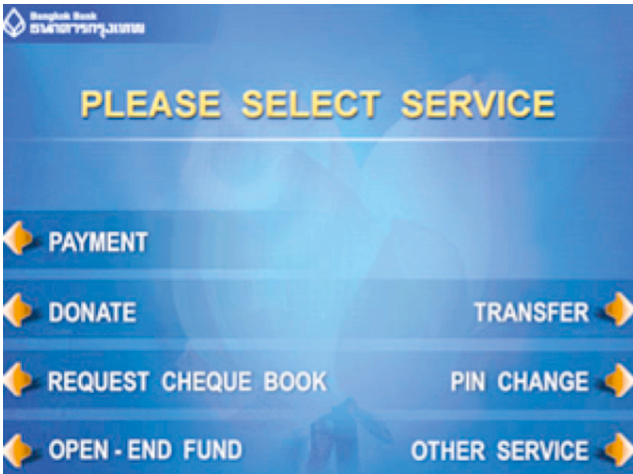

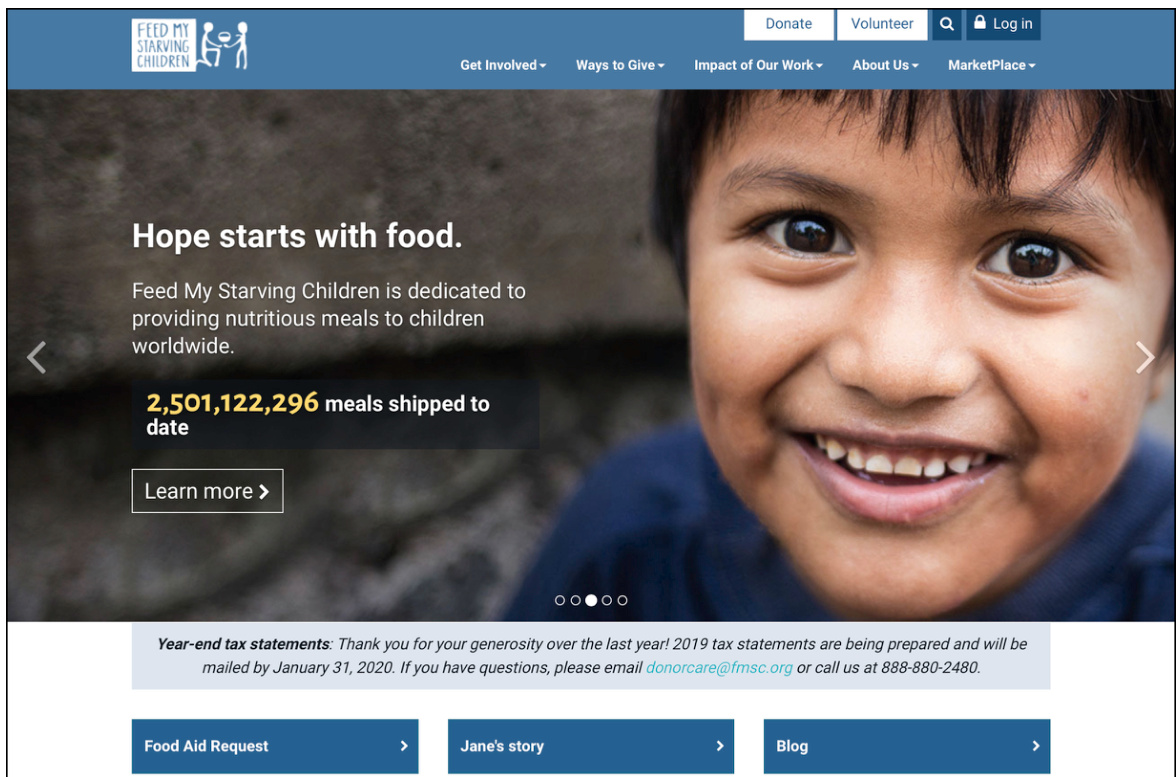

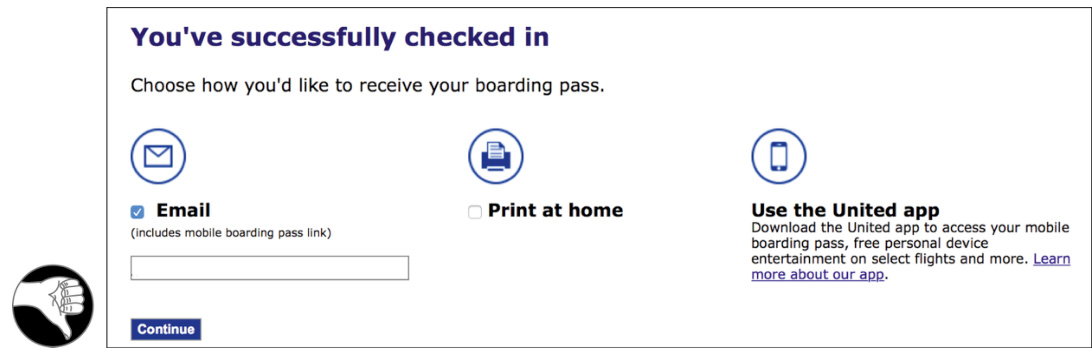

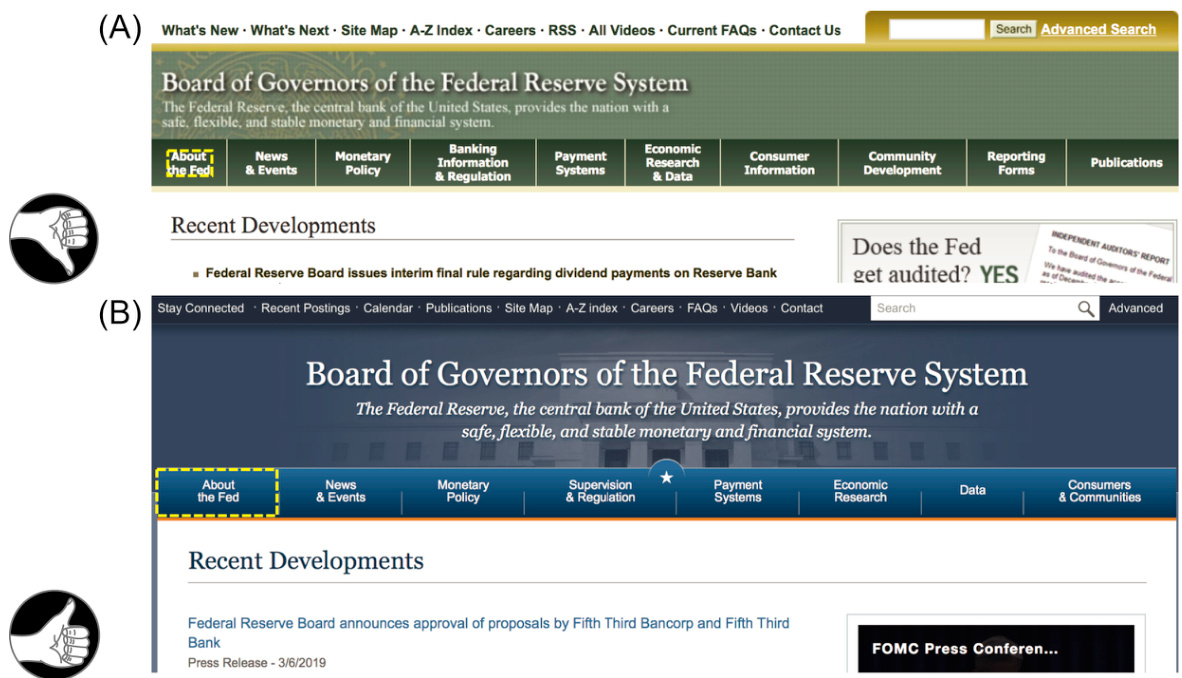

任何使用电脑、网站或者智能手机的人对桌面和文件、网页浏览器、网站和各种类型的软件应用和在线服务都有对应的心智框架。比如,当他们访问一个新网站时,有经验的网络用户期待看到网站名字和标志、导航条、一些链接,也许还有一个搜索框。当在线订购机票时,他们期待能够指定行程详细信息,查看搜索结果,选择决定的航班,并且购买机票。

由于软件用户和网站用户感知模式的存在,他们经常不仔细看就点击按钮或链接。他们对控件位置的期望更多来自在当前情况下,他们自己的框架期望他们在屏幕上看见什么。这点有时会让软件设计者觉得挫败,因为设计者期望用户看见屏幕上确实有的东西,但人类的视觉系统却不是这样工作的。

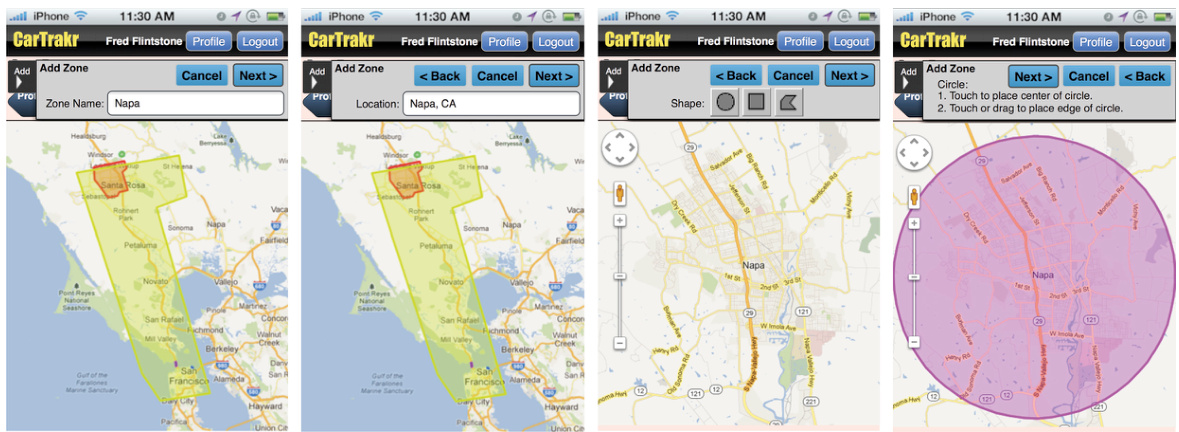

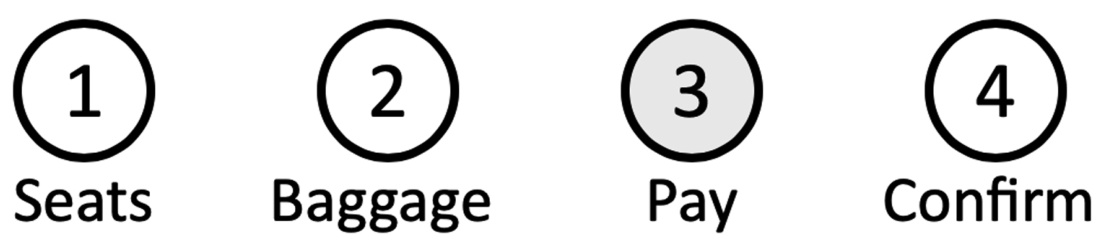

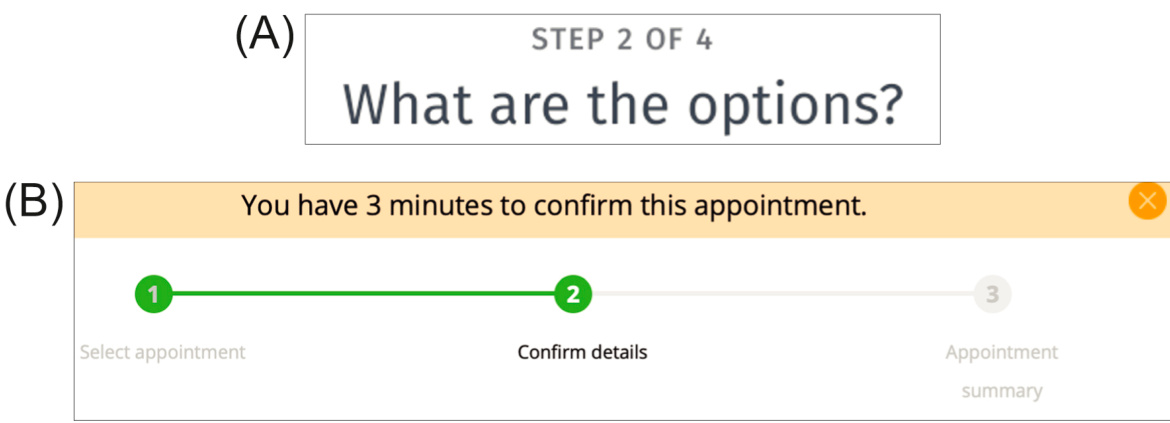

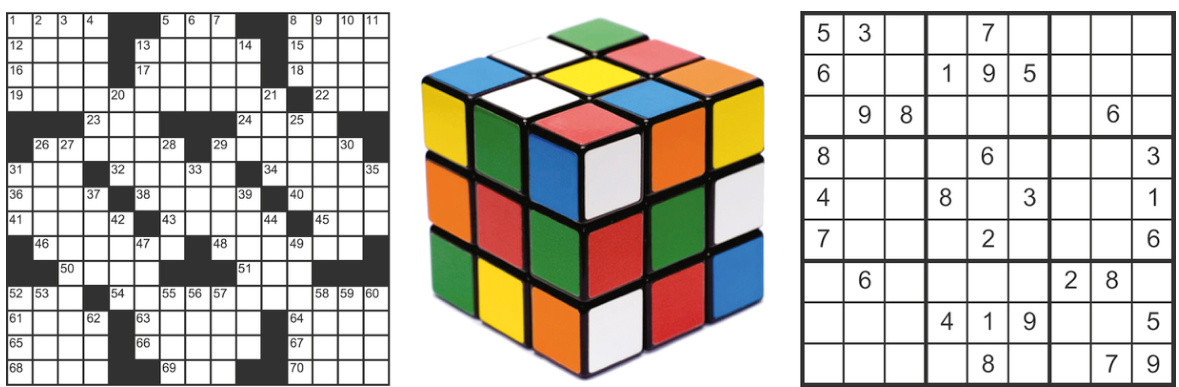

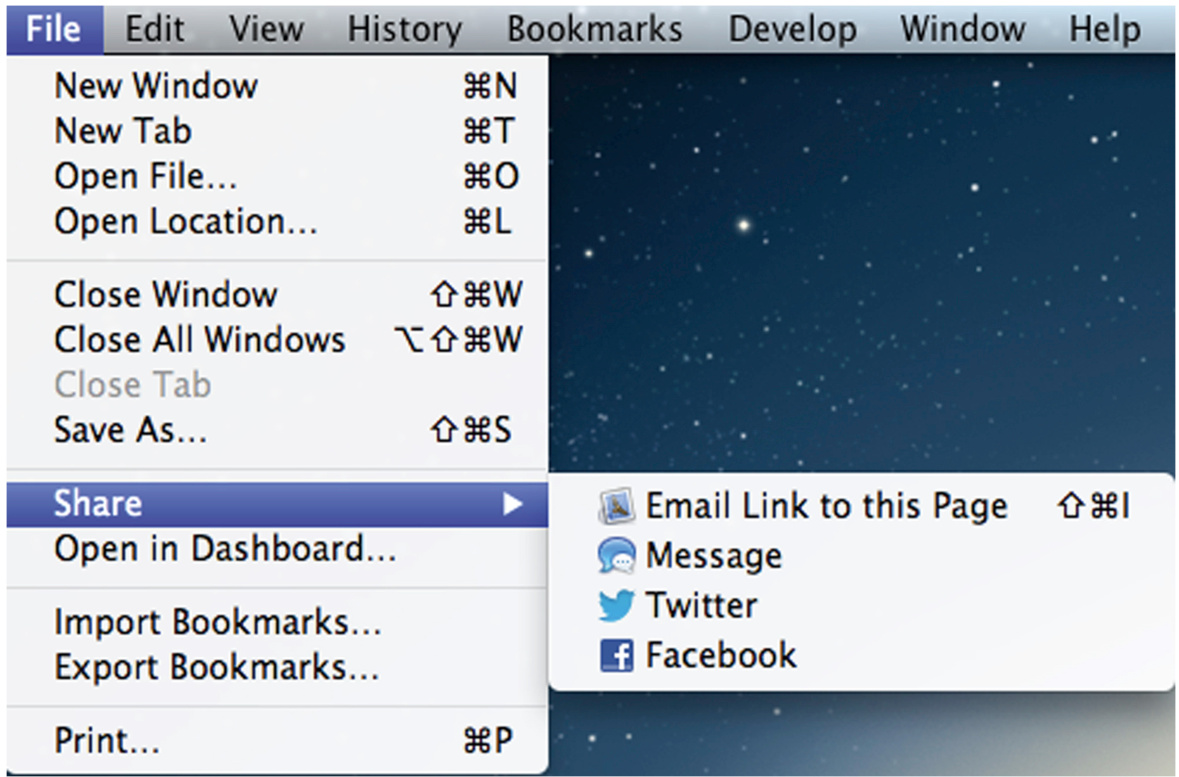

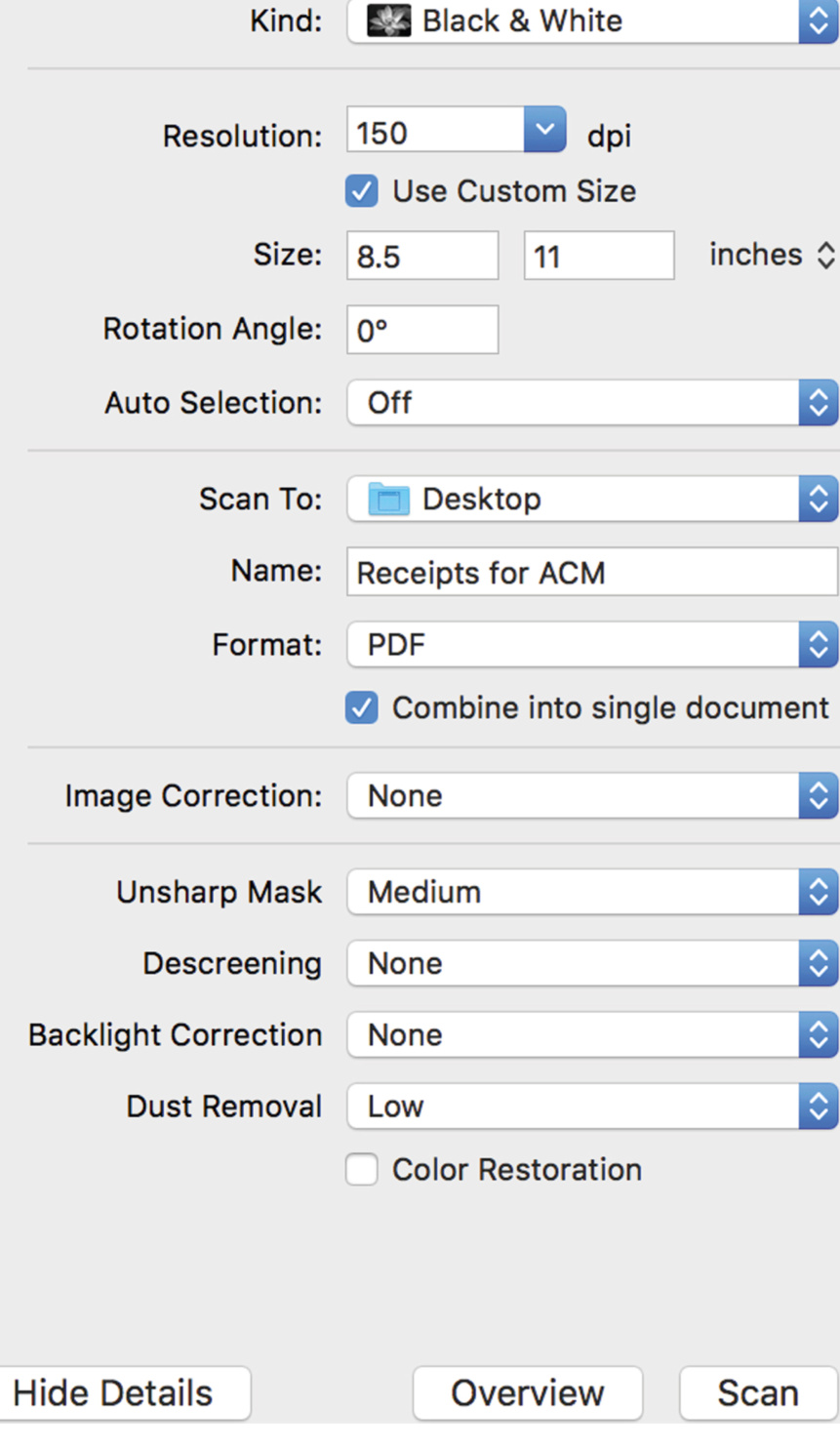

例如,如果在一个多页对话框的最后一页上的“下一步(Next)”和“返回(Back)”按钮交换了位置,许多人就不会立刻注意到(见图 1.3)。前几页上布置一致的按钮麻痹了他们的视觉系统。甚至在无心地返回了几次之后,他们可能仍然觉察不到按钮不在标准位置上。这就是为什么“控件的摆放要一致”是一个常见的用户界面设计准则。

图 1.3 用户可能始终认为下一步按钮在右侧,即使它不在那里。

类似地,在寻找某件东西时,如果它不在老地方或者看起来与往常不同,即使就在眼皮底下我们也可能视而不见。这是因为经验调整我们到期望的地方依据期望的特征去寻找。例如,如果一个网站某个表单上“提交”按钮的形状或者颜色与其他表单上的按钮不同,用户就可能找不到它。本章在关于目标如何影响感知的一节中,会深入讨论这种由预期导致的盲目性。

习惯性

经验影响感知的第三种方式被称为习惯性。重复置身于同样(或者非常类似)的感觉会让感觉系统的敏感度降低。习惯性是人们神经系统在非常低层的一个现象,它发生在神经级别。即使是非常原始的、只具有非常简单神经系统的动物,比如扁形虫和阿米巴虫,也会对重复的刺激(比如轻微的电击或者闪光)产生习惯性。具有复杂神经系统的人类,对一系列事件也会产生习惯性,从低层次(如连续的蜂鸣声)、到中间层次(如网站上闪烁的广告条)再到高层次(比如某人在每次派对上重复说同一个笑话或者某政客的长单调的演讲),都是如此。

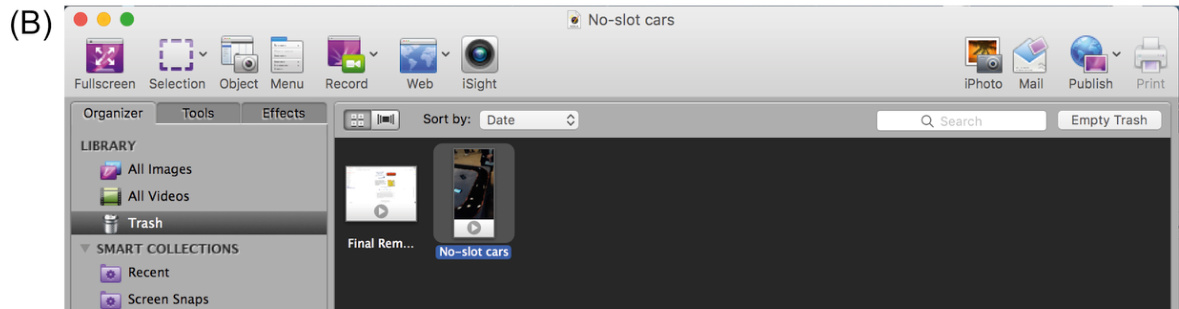

在使用电脑时,当“你是否确定”的确认框一次又一次出现,人们也能体验到习惯性。人们最开始会注意到并且或许会做出反应,但最终则会反射般直接忽视并关闭确认框。

在最近被标以“社交媒体倦怠”(Nichols,2013)、“社交媒体疲劳”或者“Facebook 假期”(Rainie 等,2013)的现象中,习惯性也是一个因素。社交网站的新用户一开始对用微博来分享体验的创新感到兴奋,但迟早会感到疲惫不堪,不愿再耗费时间阅读“朋友们”分享的各种琐事,比如,“看!我午饭吃的这份三文鱼沙拉太赞了!”

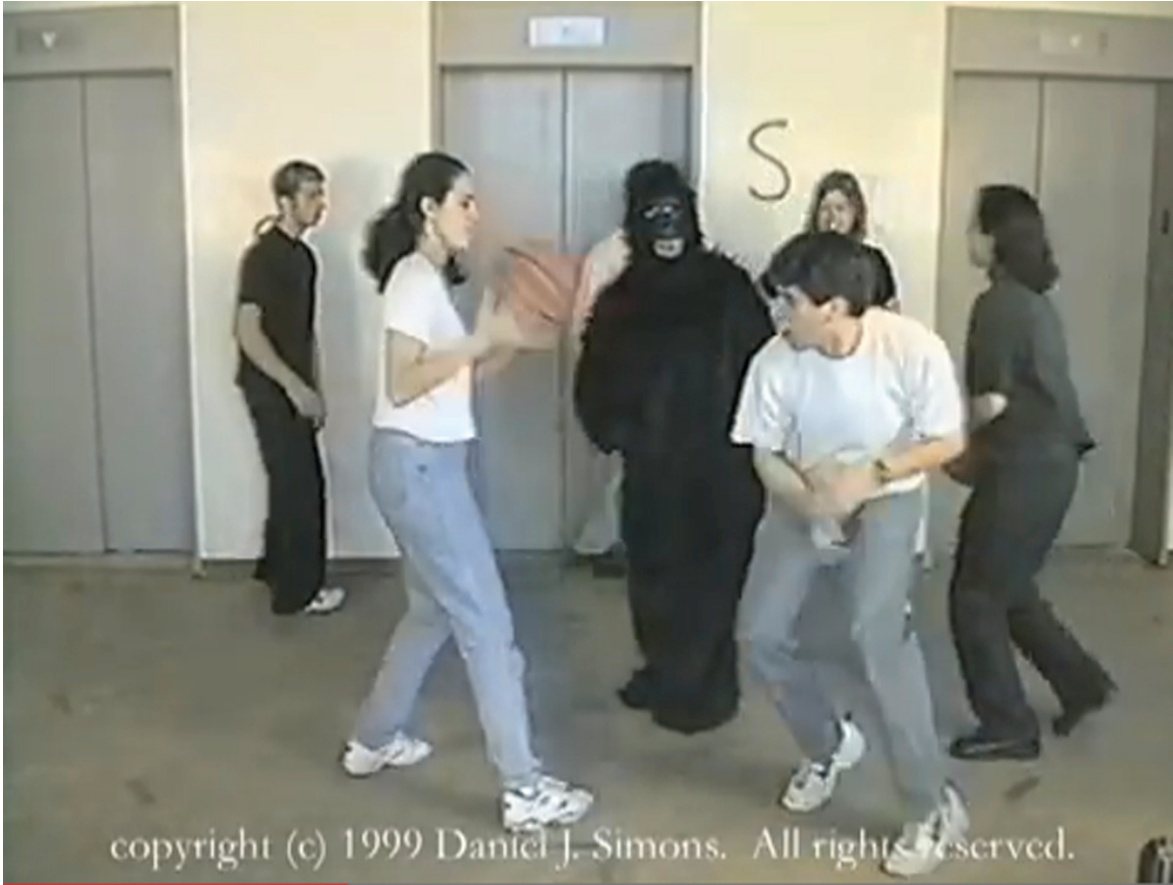

注意瞬脱

过往经验对低层感知的另一个影响,发生在人们刚刚发现或者听到某件重要的事情之后。在识别之后短暂的 0.15 秒到 0.45 秒之间,即使耳朵和眼睛正常工作,人们也接近于失聪而且无视其他视觉刺激。研究者们把这个现象称为注意瞬脱(Raymond 等,1992,Stafford 和 Webb,2005),认为这是由于大脑的感觉与注意力机制在短时间内完全用于处理第一个识别而产生的。

一个经典的例子:你在一节正在进站的地铁车厢内,计划与两位朋友在地铁站见面。当地铁到达时,你的车厢经过了一位朋友,你透过车窗短暂地看到了他。在下一秒钟,又经过了另一位朋友,但你却没注意到她。这是因为,当她的影像抵达你的视网膜时,你正好因为认出了第一位朋友而处于注意瞬脱中。

当人们使用基于电脑的系统和在线服务时,如果事情连续发生得太快,他们会因为注意瞬脱而错过一些信息或者事件。当下制作纪录影片有一个流行的手段,就是连续快速展示一系列静态照片。这个方式是非常容易产生注意瞬脱的:如果一个图片真的吸引了你的注意力(比如对你有特别的意义),你可能就会错过紧接其后的一两张图片。相比之下,自动播放的幻灯片(比如在网站或者信息资讯机上)中的一张引人注目的图片是不大可能造成注意瞬脱的(即错过下一张图),因为每张图片都一般有几秒钟显示时间。

环境影响感知

Perception Biased by Current Context

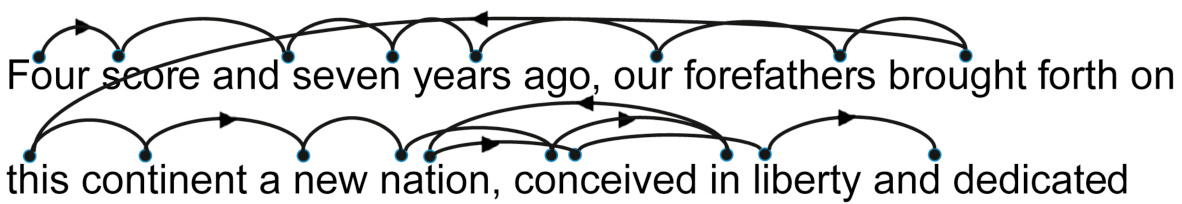

当我们试图去理解视觉如何工作时,很容易认为它是一个自下而上的过程,将边、线条、角度、弧线和纹路等基本要素组成图案并最后形成有意义的事物。以阅读为例,你可能假设我们的视觉系统首先识别字母,把它们组合成单词,再将单词组合成句子,如此继续。

但视觉感知,尤其是阅读,不完全是一个自下而上的过程,其中也有自上而下的作用。例如,包含某个字母的单词能够影响我们对这个字母的判断(见图 1-4)。

图 1-4 同样的字符受其附近的字母影响而被感觉成 H 或 A

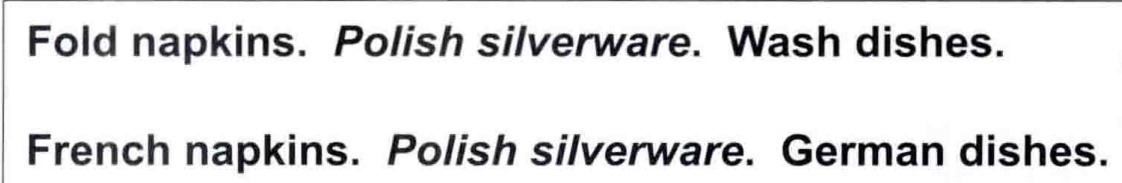

类似地,对一句话或者一段话完整的理解甚至能够影响我们所看到的单词。例如,同样的字母序列可以因前后段落含义的不同而被理解成不同的单词(见图 1-5)。

图 1-5 同样的短语因其所在的短语组不同而有不同的解读

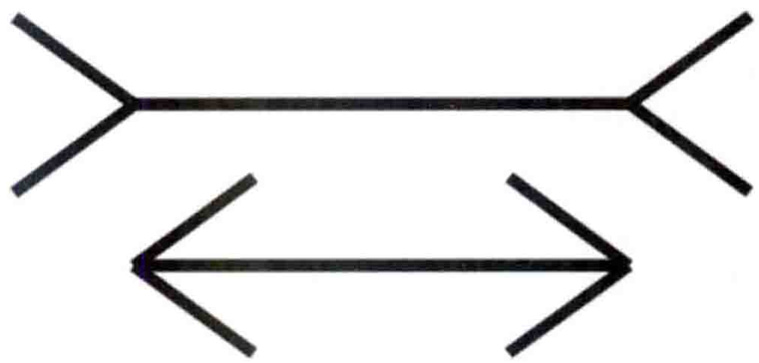

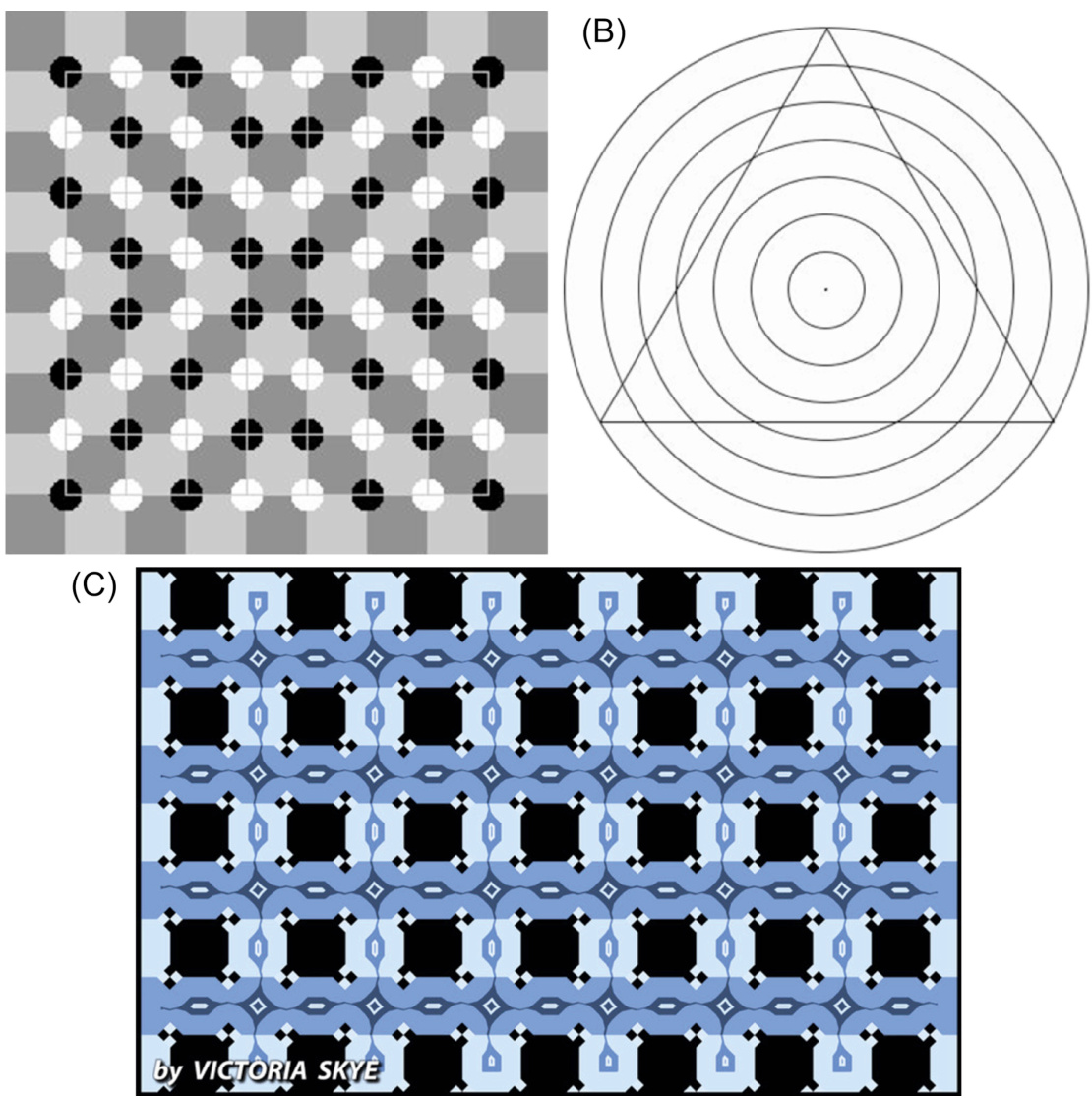

视觉受环境因素影响的偏差在不仅仅在阅读中出现。Muller-Lyer 错觉就是一个著名的例子(见图 1-6):两条水平线,一条有朝外指向的“翅”,另一条有着朝内指向的“翅”,尽管它们相同长度,但不同的“翅”使得我们的视觉系统觉得上方的线比下方的线更长。这类视错觉(见图 1-7)欺骗了我们,因为我们的视觉系统并不使用精确的、最佳的处理方式来感知世界。视觉系统在进化中发展,这是一个半随机的过程,不断叠加各种应急的,通常非完备且不精确的方案。它在大部分时间里运转正常,但包含许多粗略估计、拼凑、修补和一些在某些情况下彻底导致问题的 bug。

图 1-6 Muller-Lyer 错觉:同样长度的水平线看起来不一样长

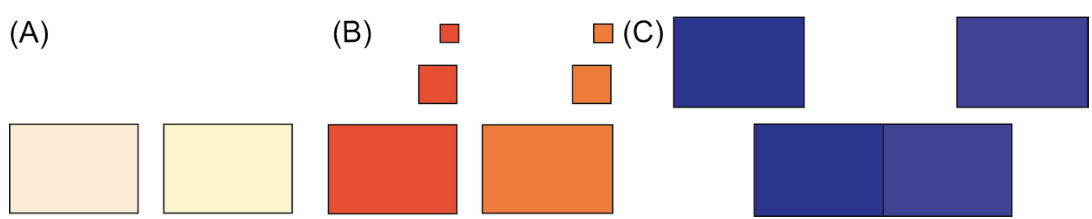

图 1-7(A)棋盘中间并未凸起:(B)三角形的边没有弯曲 (C)红色的竖线是平行的

图 1-6 和图 1-7 中的例子显示,视觉被视觉环境所影响。然而,在当前环境下不同感官之间也会有感知的偏差。五官的感觉会同时相互影响。我们的触觉感受可能会被听到的、看到的或者闻到的所影响,视觉会被听觉影响,听觉也会被视觉影响。以下是我们的视觉影响听觉的两个例子。

McGurk 效应

如果你观看一个视频,其中有人说着“吧、吧、吧”,接着“嗒、嗒、嗒”,然后“哇、哇、哇”,但音频一直是“吧、吧、吧”。你将会通过观看说话者的嘴唇运动而不是实际听到的来辨认他说的音节。只有当闭上眼睛或者转移目光,你才能真正听到实际语音发出的音节。我打赌你们不知道自己可以读唇,但事实上人们一天里这么做的次数相当多。

腹语

腹语表演者并不转移自己的声音,他们仅仅是学会了不动嘴说话。观众的大脑感觉是与声音最近的那个动着的嘴在说话,就是腹语者表演用的玩偶的嘴(Eagleman,2012)。

反过来,听觉影响视觉的一个例子是幻觉闪光效果。当屏幕上的某一点短暂地闪了一下,但伴随着两个快速的蜂鸣声,就会看起来像闪了两下。类似地,感觉到的闪光频率也可以随点击鼠标的频率变化(Eagleman,2012)。

后续章节将解释人脑中的视觉感知、阅读和认知功能。现在就简单地表述为:识别一个字母、一个单词、一张脸或者其他任何物体的神经活动,都包含了环境刺激产生的神经信号的输入。这个环境包括感知到的其他邻近对象和事件,甚至由环境激活的、对以往感知到的对象和事件的记忆。

环境不仅影响人的感知,也影响低级动物的感知。一位朋友经常带着她的狗开车出门办事。一天当她开进自家车道时,有一只猫在前院。她的狗看见了就开始叫。我的朋友一打开车门,狗就蹄出去追那只猫,猫立刻转身跳进灌木丛中逃跑了。狗也扎进灌木丛,但没逮到猫。那之后的一段时间里,这条狗就一直很烦躁不安。

之后,在我的朋友住在那里的那段时间,每次她开车带着狗回到家,它就兴奋地叫起来,并在车门打开那一刻跳出去,冲过院子,跃人灌木丛。没有猫在那里,但那并不重要。乘着车回到家对这狗来说已经足够让它看见甚至可能闻到一只猫。然而,如果是走回家,比如每天遛完它后,“猫幻影”就不会发生。

目标导向的感知偏差

Perception Biased by Goals

除了受过去经验和当前情境的影响外,我们的感知还受到我们对未来目标和计划的 影响。具体来说,我们的目标:

• 引导我们的感知器官,让我们从周围的世界中采样我们所需要的信息;

• 过滤我们的感知——与我们的目标无关的事物往往会预先无意识地被过滤掉,也就不会被我们的主观意识注意到。

例如,当人们在软件里或者网站上寻找信息或者某个功能时,他们并不会认真阅读,只是快速而粗略地扫描屏幕上与目标相关的东西。他们不是仅仅忽略掉与目标无关的东西,而是经常根本注意不到它们。

现在就来体会一下。请在图 1-8 中的工具箱里找到剪刀,然后立刻回到这里。

图 1-8 工具箱:这里有剪刀吗

你发现剪刀了吗?现在不去看工具箱,你能说出来那里面有没有螺丝刀吗?

除了视觉,我们的目标还过滤其他感官的感知。一个熟悉的例子是“鸡尾酒会”效应。如果你在一个拥挤的酒会上与某人谈话,你能把大部分注意力放在他说的话上,即使身边还有许多人在对话。你对谈话的兴趣越大就越能过滤掉周围的对话。如果你对谈话内容感到乏味了,多半就会越来越多地听到周围的谈话。

这个效应首次记录于对空中交通管制员的研究中。即使控制室的同一个扩音器传出在同一个频道上同时进行的许多不同对话,空中交通管制员们仍然能够与被指派飞机上的飞行员进行对话(Arons,1992)。研究表明,在多个同时进行的对话中,专注于一个对话的能力不仅取决于对谈话内容感兴趣的程度,也取决于客观因素,如在杂音中熟悉的语音、常见“噪声”的量(如碗碟的碰撞声或者喧闹的音乐)以及能否预见谈话对象要说什么(Arons,1992)。

目标对感知的过滤在成人身上特别可靠,成人比儿童对目标更专注。儿童更容易被刺激驱使,目标较少地过滤他们的感知。这种特点使得他们比成人更容易分心,但也使得他们观察时更不容易产生偏差。

一个客厅游戏展示了年龄差异在感知过滤上的差别。它类似刚才的“工具箱”练习。大多数人的家里都有一个专门放厨房器具或者工具的抽屉。请一个人从客厅到那个抽屉所在的房间,要求他拿来某个工具,比如量勺或者水管扳手。当他带着工具回来时,问他在抽屉里是否有另外某个工具。大部分成人不记得抽屉里还有什么其他东西。但孩子们通常能够告诉你那里面还有什么其他东西,前提是他们完成了任务,而没有被抽屉里其他很酷的玩意彻底吸引。

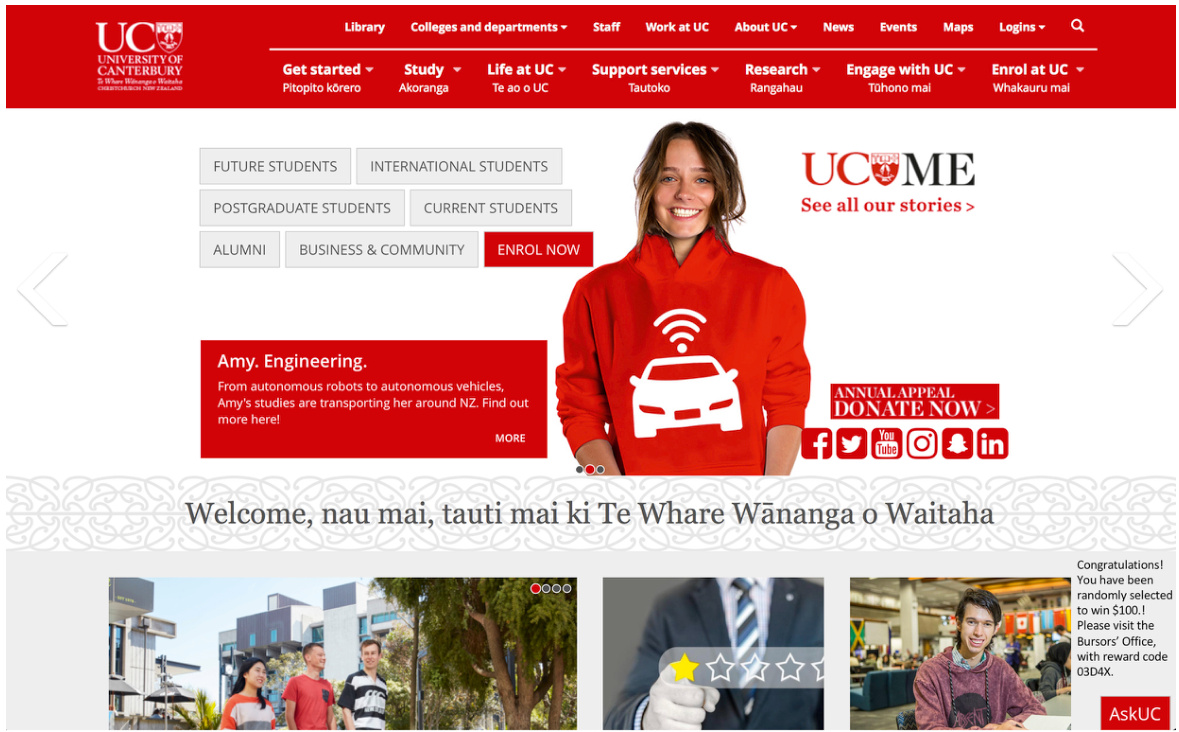

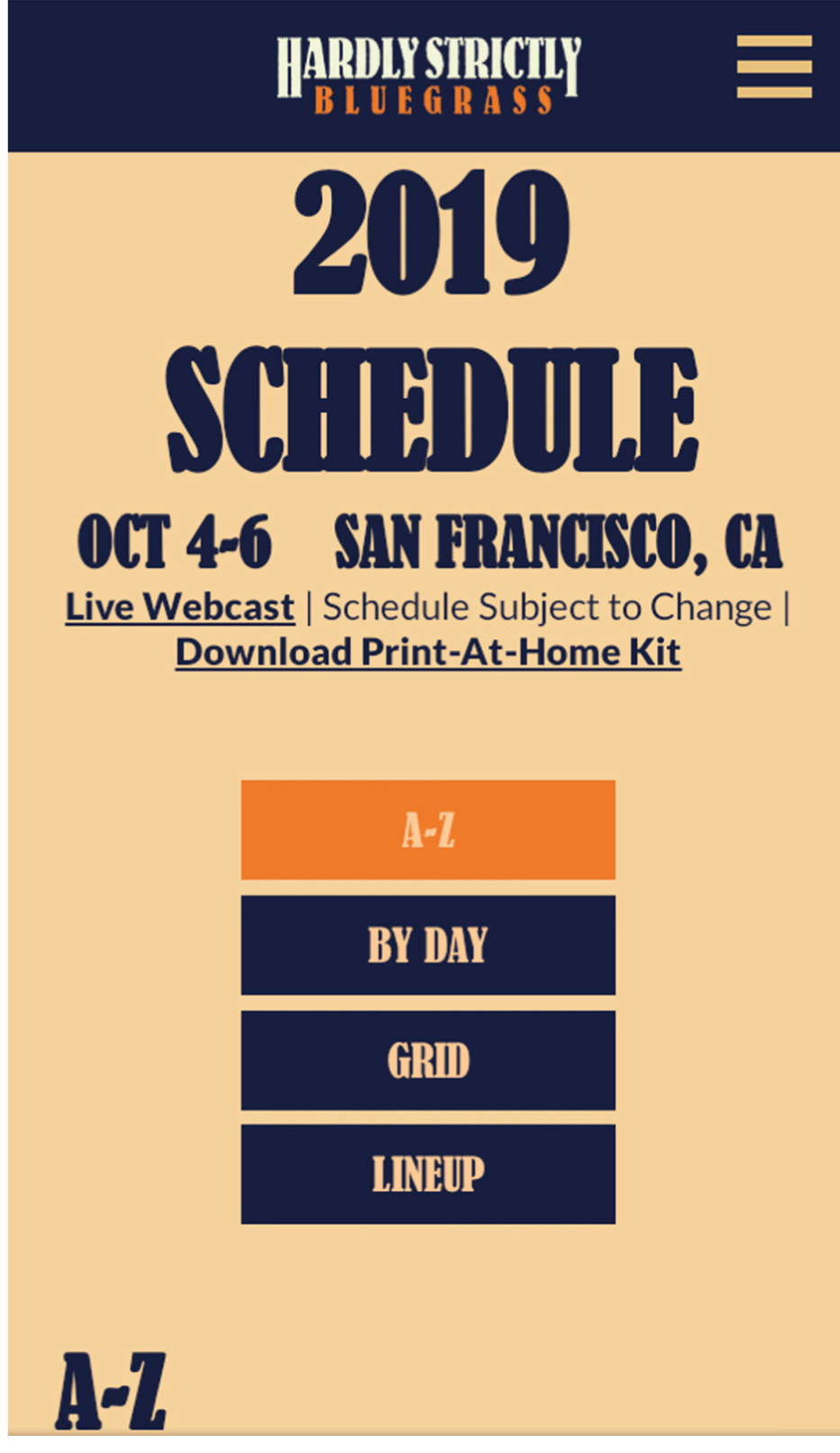

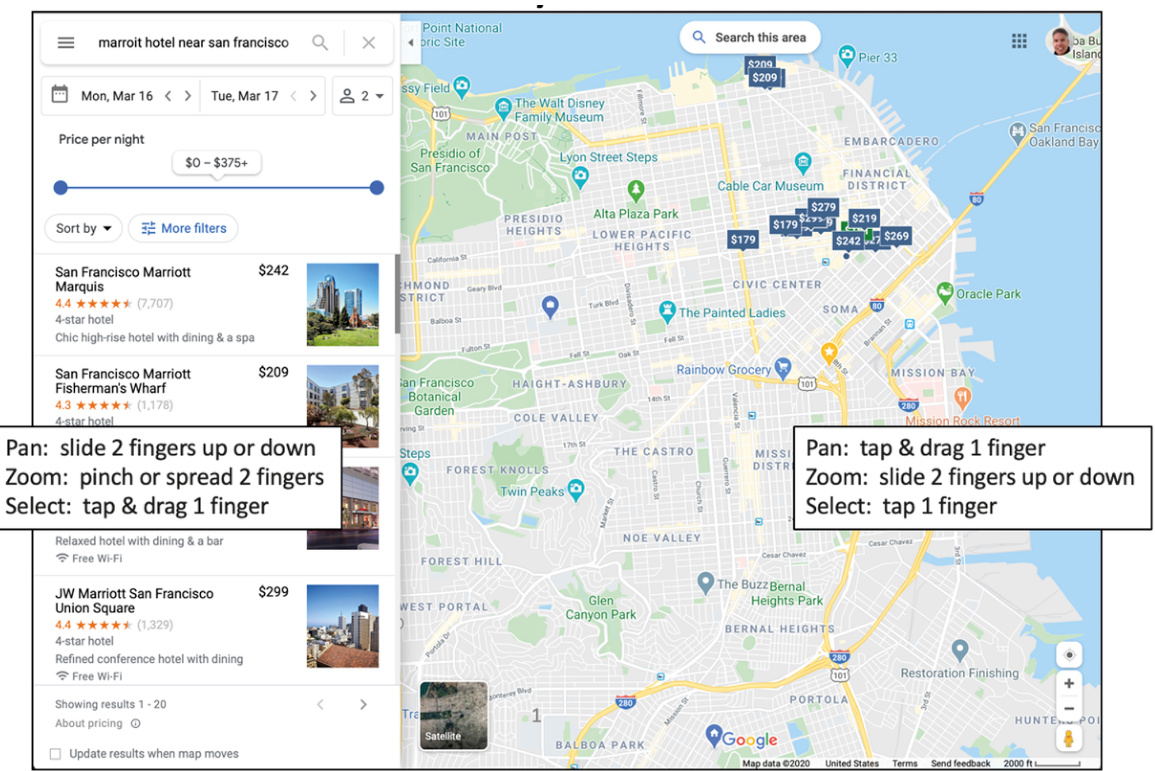

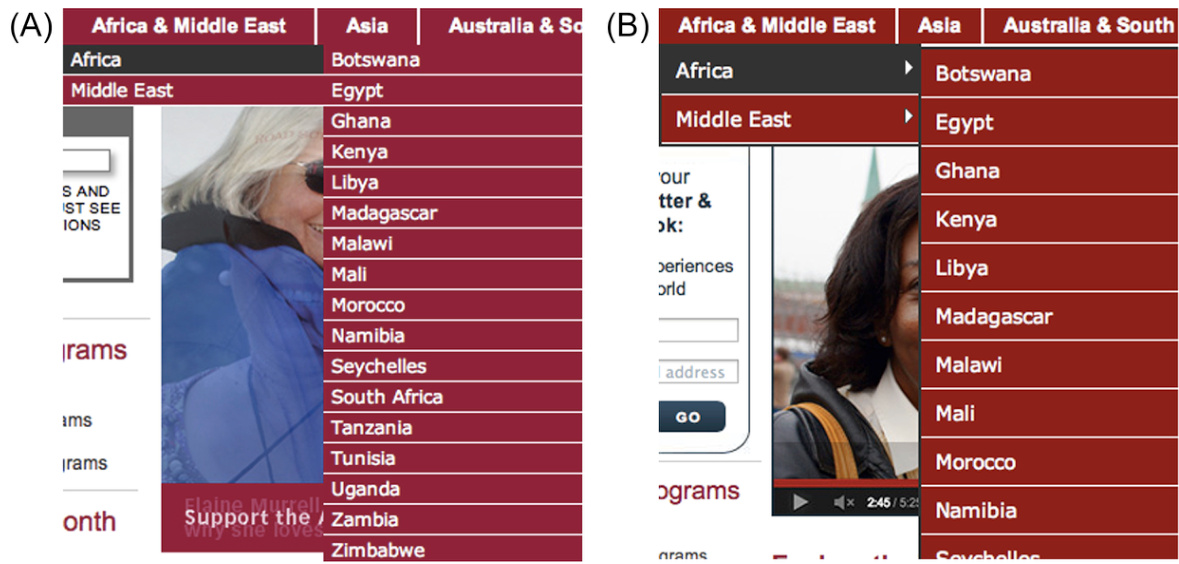

感知过滤在网站导航中也能观察到。假设我要你去新西兰的坎特伯雷大学(见图 1-9)的主页并找出对计算机科学系研究生提供资助的信息。你会扫视网页并可能很快地点击那些含有与目标相关单词的链接:Departments(“院系”,左上)、Scholarships(“奖学金”,中间),还有 PostgraduateStudents(“研究生”,左下)。如果你是个“搜索型”的人,也许就直接到搜索框(右上)输人与目标相关的单词,然后点击“Go”。

图 1-9 坎特伯雷大学主页:网页导航过程包含感知过滤

不论你是浏览还是搜索,都很可能没注意到自己被随机地挑中赢得 100 美元(右下)而直接离开了主页。为什么?因为那与你的目标无关。

What is the mechanism by which our current goals bias our perception? There are two:

我们当前的目标如何影响我们的感知?机制有两种:

影响我们注意什么

感知是主动的,不是被动的。感知不是对周围事物的简单过滤,而是对世界的体验以及对需要理解的东西的获取。我们始终移动眼睛、耳朵、手、脚、身体和注意力去寻找周围与我们正在做或者正要做的事最相关的东西(Ware,2008)。如果在一个网站上找园区地图,那些能够引导我们去完成目标的对象就会吸引我们的眼睛和控制鼠标的手。我们会或多或少地忽略掉与目标无关的东西。

使我们的感知系统对某些特性敏感

在寻找某件物品时,大脑能预先启动感官,使得它们对要寻找的东西变得非常敏感(Ware,2008)。例如,要在一个大型停车场找一辆红色轿车时,红颜色的车会在我们扫视场地时跃然而出,而其他颜色的车就几乎不会被注意到,即使我们的确“看到”了它们。类似地,当我们试图在一个黑暗拥挤的房间里寻找自己的伴侣时,大脑会对我们的听觉系统进行“编程”,从而对她或他的声音的频率组合非常敏感。

设计时将感知的影响因素考虑在内

这些对感知的影响因素对于用户界面设计有以下三点启发。

避免歧义

避免显示有歧义的信息,并通过测试确认所有用户对信息的理解是一致的。当无法消除歧义时,要么依靠标准或者惯例,要么告知用户用你期望的方式去理解歧义之处。

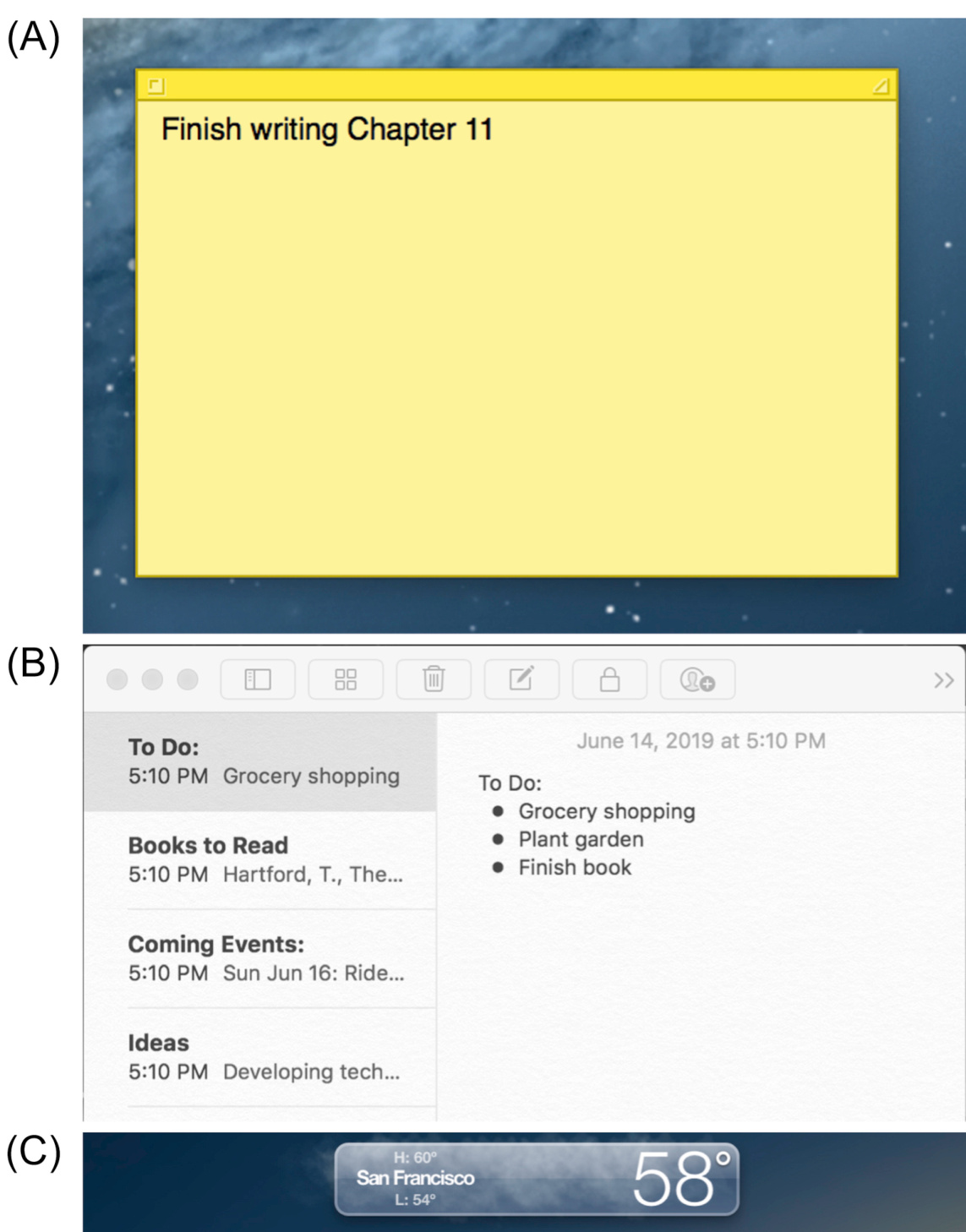

例如,数字设备上的显示常常给用户界面组件添加阴影,使其看起来相对于背景表面更突出(见图 1.10)。这种显示方式依赖一个大多数有经验的电脑用户都熟悉的惯例一光源在屏幕的左上角。如果一个物体是以光源在不同的位置来渲染的话,用户则无法看出它是凸起还是凹陷。

图 1-10 数字设备屏幕上的组件会添加阴影,使其看起来像是在背景上方漂浮,但这种感知只有在假设模拟光源在左上角时才有用。

保持一致

将信息和控件放置在一致的位置。不同页面上提供的相同功能的控件和数据显示应该摆放在每一页上相同的位置,而且它们还应该有相同的颜色、字体和阴影等。这样的一致性能让用户很快地找到和识别它们。

理解目标

用户去用一个系统是有目标的。设计者应该了解这些目标,要认识到不同用户的目标可能不同,而且他们的目标强烈左右他们能感知到什么。在一次交互的每个点上,确保提供了用户需要的信息,并非常清晰地对应到一个可能的用户目标,使用户能够注意到并使用这些信息。

重要要点

• 人类的感知并不是对“世界”中事物的准确反映。它受到我们的经验、当前环境和我们的目标的影响。

• Past experience can bias our perception by “priming” our perceptual systems to detect certain objects and events as well as “priming” them not to detect other objects and events. Repeated perception of an event over a short interval can cause habituation, increasing the chances that we will miss later occurrences of the event. With long-term experience, we develop frames for familiar situations that make us perceive things that aren’t there or miss things that are.

• 过去的经验可以通过“启动”我们的感知系统来偏置我们的感知,使我们更容易检测到某些物体和事件,同时“启动”它们不去检测其他物体和事件。在短时间内重复感知一个事件会导致习惯化,增加我们错过后来发生的该事件的可能性。长期的经验使我们熟悉的情况形成框架,使我们感知到不存在的事物或错过存在的事物。

• Because our attention has limited capacity, when it is overloaded we can miss other objects and events. This is called attentional blink.

• 由于我们的注意力有限,当注意力超负荷时,我们会错过其他物体和事件。这被称为注意力盲点。

• 感知以两种方式同时运作:• 我们对整体物体和事件的感知基于对部分的感知。• 对部分的感知基于对整体的感知。

• 我们对物体和事件的感知可能受到我们情绪状态的影响。

• 我们的感知系统——尤其是我们的视觉系统——包括进化上的捷径和缺陷,这些会导致我们对某些刺激产生错误的感知。

• 我们的目标和计划强烈影响我们注意什么,因此也影响我们感知什么。

• 通过遵循基于人类感知方式的设计指南,设计师可以创建与将要使用它们的人相匹配的应用程序、网站和设备。

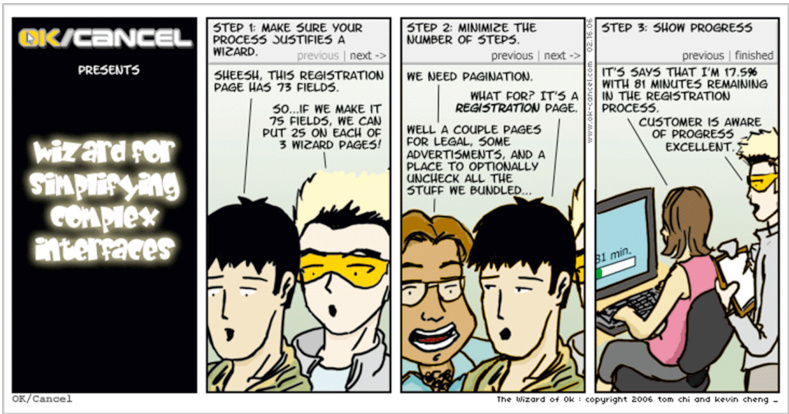

2Multistep screen sequences are called wizards in user-interface design jargon.

2在用户界面设计行话中,多步骤屏幕序列称为向导。

3 Chapter 14 discusses the attentional blink interval along with other perceptual intervals.

3 第 14 章讨论了注意力闪烁间隔以及其他感知间隔。

4For an example, search YouTube for “history of the world in 2 minutes.”

4例如,在 YouTube 上搜索“2 分钟的世界历史”。

5See youtube.com/watch?v

5 查看 youtube.com/watch?v

第二章 :我们的视觉是为了看到结构而优化

Chapter 2: Our Vision is Optimized to See Structure

摘要

本章介绍了描述人类视觉感知的格式塔原则:邻近性、相似性、连续性、闭合性、对称性、图底关系和共同命运,以及每个原则如何影响用户界面设计。例如,邻近性原则是指显示中对象之间的相对距离会影响人们对对象是否以及如何组织成子组的感知;彼此靠近的对象(相对于其他对象)看起来是分组的,而相距较远则不是。

关键词

Ambiguity; Background; Closure; Common fate; Continuity; Displays; Figure-ground; Foreground; Gestalt principles; Grouping; Perception; Proximity; Similarity; Spacing; Symmetry; Vision; Visual; Visual design

两可性;背景;闭合性;共同命运;连续性;显示;图底关系;前景;格式塔原则;分组;感知;邻近性;相似性;间距;对称性;视觉;视觉;视觉设计

20 世纪早期,一个由德国心理学家组成的研究小组试图解释人类视觉的工作原理。他们观察了许多重要的视觉现象并对它们编订了目录。其中最基础的发现是,人类视觉是整体的:我们的视觉系统自动对视觉输入构建结构,并且在神经系统层面上感知形状、图形和物体,而不是只看到互不相连的边、线和区域。“形状”和“图形”在德语中是 Gestalt,因此这些理论也就叫做视觉感知的格式塔(Gestalt)原理。

如今的感知和认知心理学家更多是把格式塔原理视为描述性的框架,而不是解释性和预测性的理论。如今的视觉感知理论更倾向基于眼球、视觉神经和大脑的神经心理学(见第 4 章到第 7 章)。

并不意外,神经心理学家的发现支持了格式塔心理学家的观察结果。我们像其他动物一样,依据整体的对象来感知周围的环境—这是有神经系统基础的(Stafford&Webb,2005;Ware,2008)。因此,格式塔原理虽然不是对视觉感知的基础性解释,但仍然是一个合理的描述框架。格式塔原理也为图形和用户界面设计准则提供了有用的基础(Soegaard,2007)。

对我们当前的讨论,最重要的格式塔原理有:接近性原理、相似性原理、连续性原理、封闭性原理、对称性原理、主体/背景原理和共同命运原理。在后续小节中,我会介绍每个原理,并列举静态图形设计和用户界面设计的例子。

格式塔原理:接近性

接近性原理是指,物体之间的相对距离会影响我们感知它们是否以及如何组织在一起。互相靠近(相对于其他物体)的物体看起来属于一组,而那些距离较远的就不是。

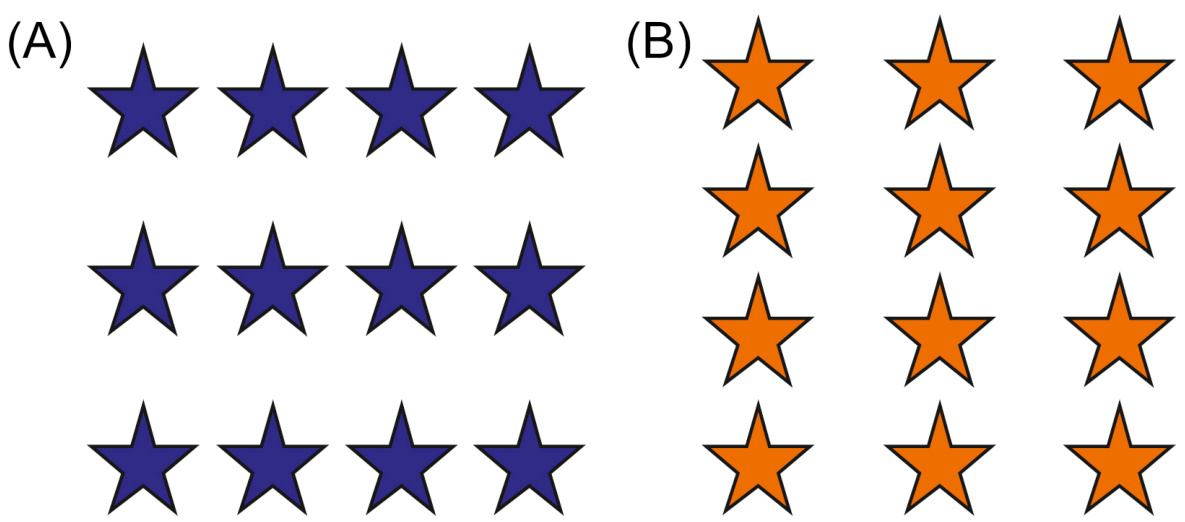

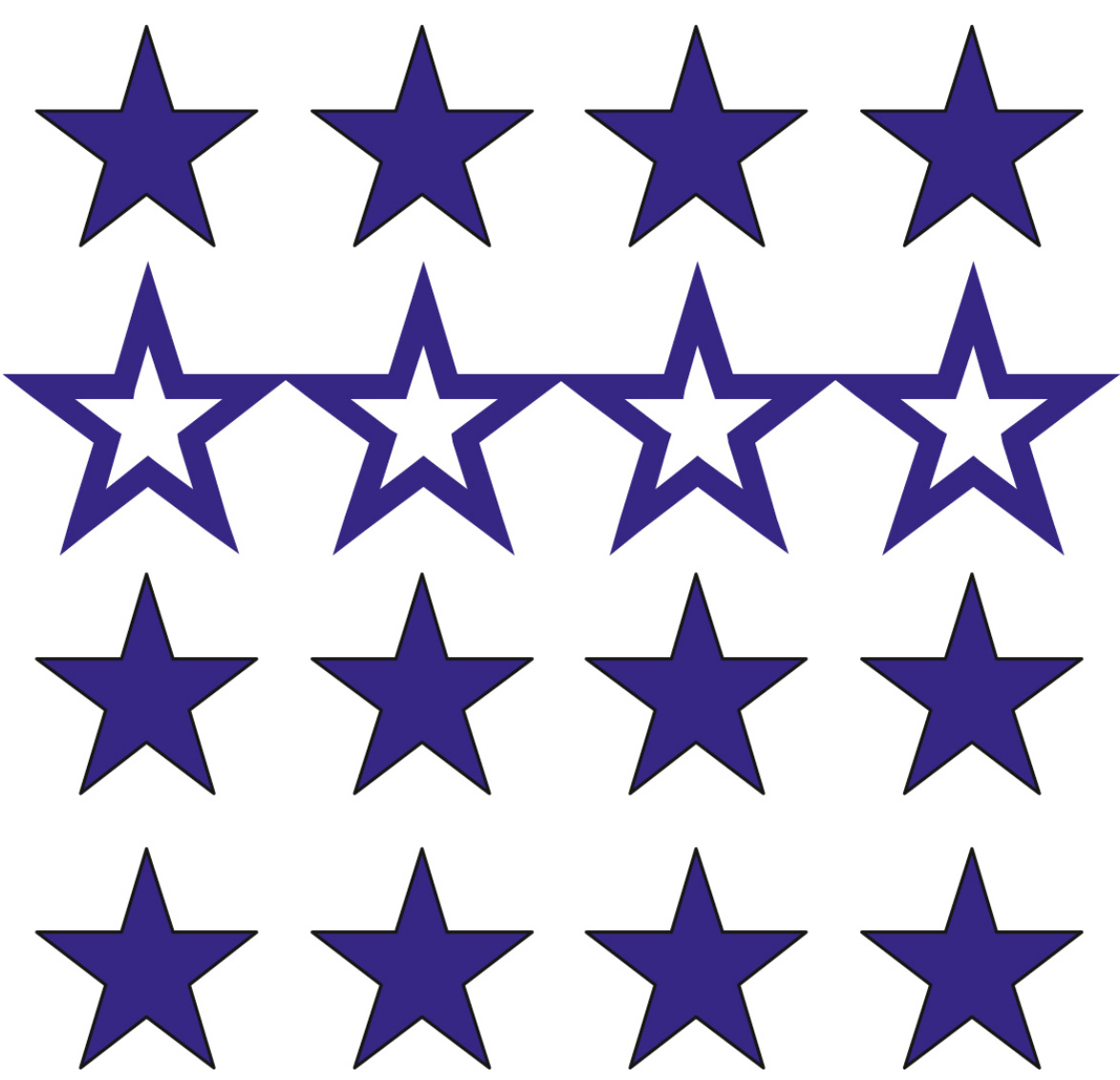

图 2-1 接近性:相互靠近的物体看起来属于一组。A 图为成行的星,B 图为成列的星

在图 2-1 中,左边的星相互之间在水平方向上比在垂直方向上靠得更近,因此我们看到星排成三行;而右边的星在垂直方向上更接近,因此我们看到星排成三列。

虽然图 2.1 中的星星看起来很相似,但当物体彼此靠近时,它们并不一定需要看起来相似才能显得成组。例如,在图 2.2 中,组的定义是由物体之间的距离决定的,而不是它们看起来怎么样。

图 2-2 近似性:即使看起来不相似的物体如果靠得近也会显得成组。

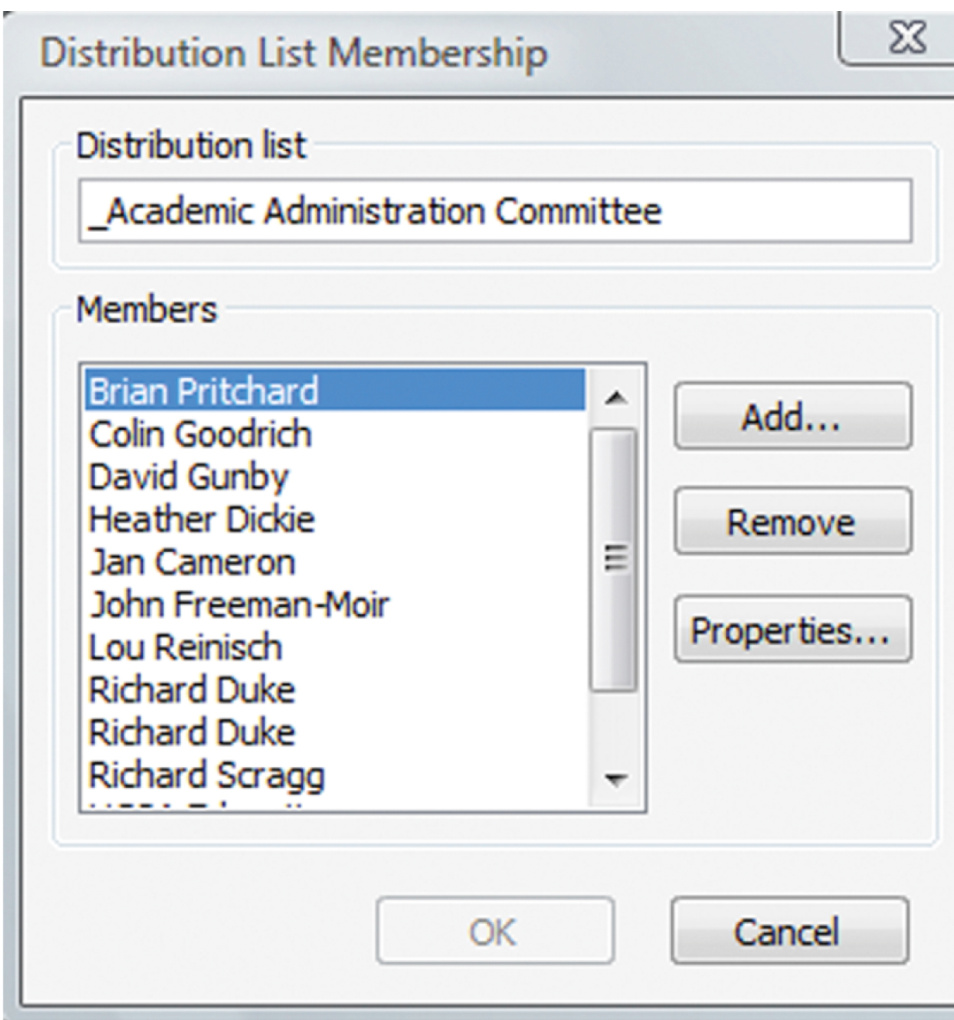

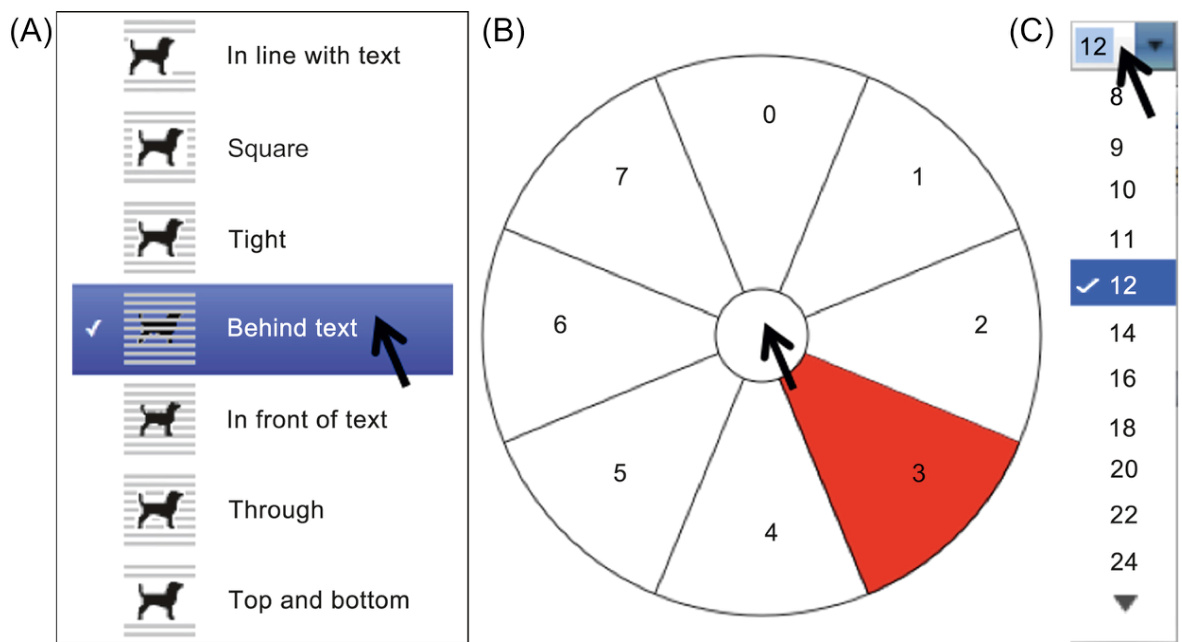

接近性原理在软件、网站和电子设备中布置控制面板或数据表单时非常有用。不知道接近原则的设计师有时会使用分组框和水平或垂直线来分隔控制组和数据显示。

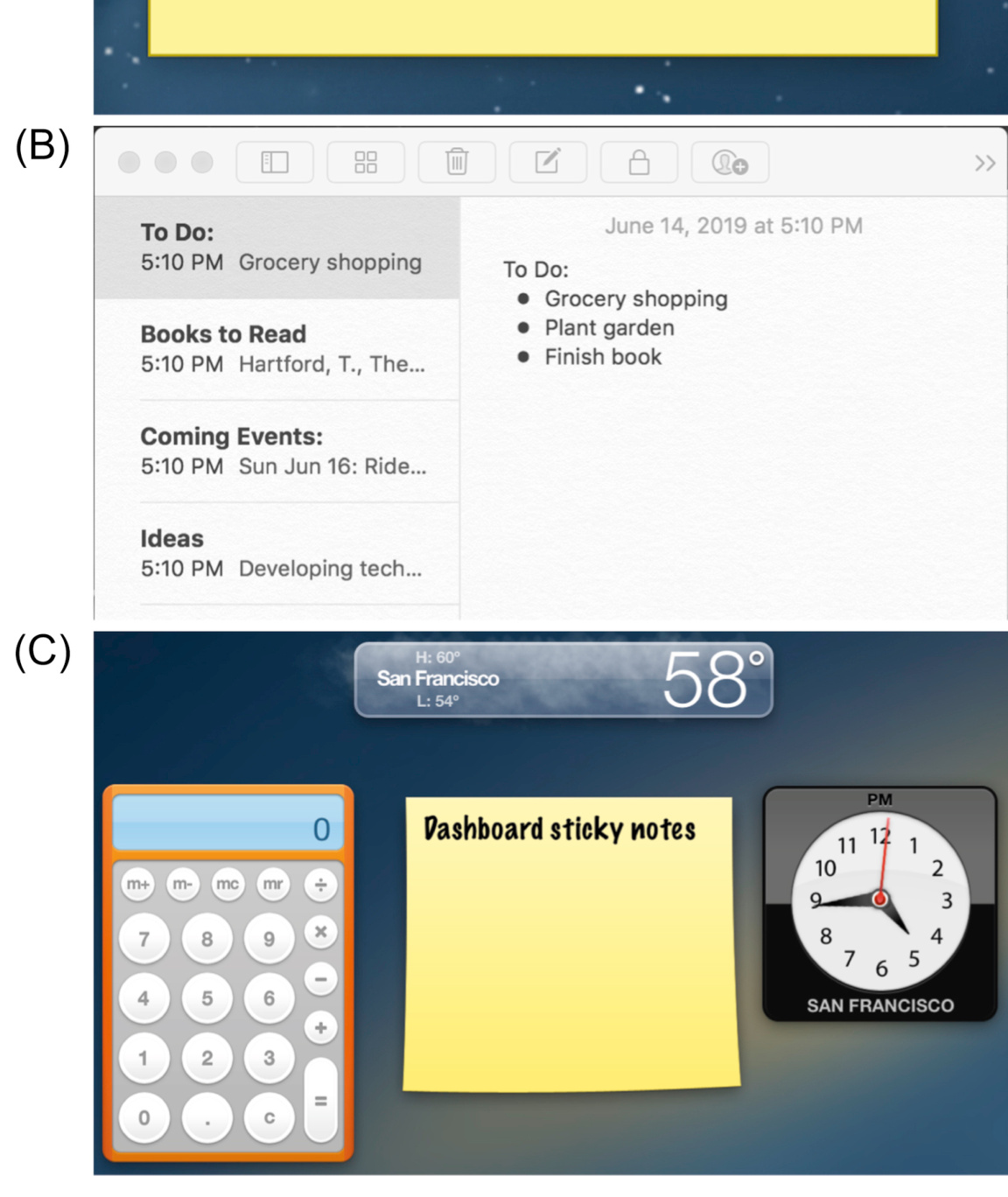

例如,Outlook 的“分发列表成员”对话框使用接近原则将添加…、删除和属性…按钮组合在一起,但随后使用不必要的分组框小部件将其与列表框关联(见图 2.3)。甚至更不必要的是标有“分发列表”的分组框,因为它只包含一个单选框。“围绕单个项目的分组框”是一种常见的 UI 设计错误(Johnson,2007)。

图 2-3 在 Outlook 的分发列表成员的对话框中,操作列表按钮放置在一个分组框里,与窗口控制按钮分开

然而,根据接近性原理,可以通过拉近某些对象之间的距离,拉开与其他对象的距离使它们在视觉上成为一组,而不需要分组框或者可见的边界。此外,邻近性可以分层应用以定义子组的组。

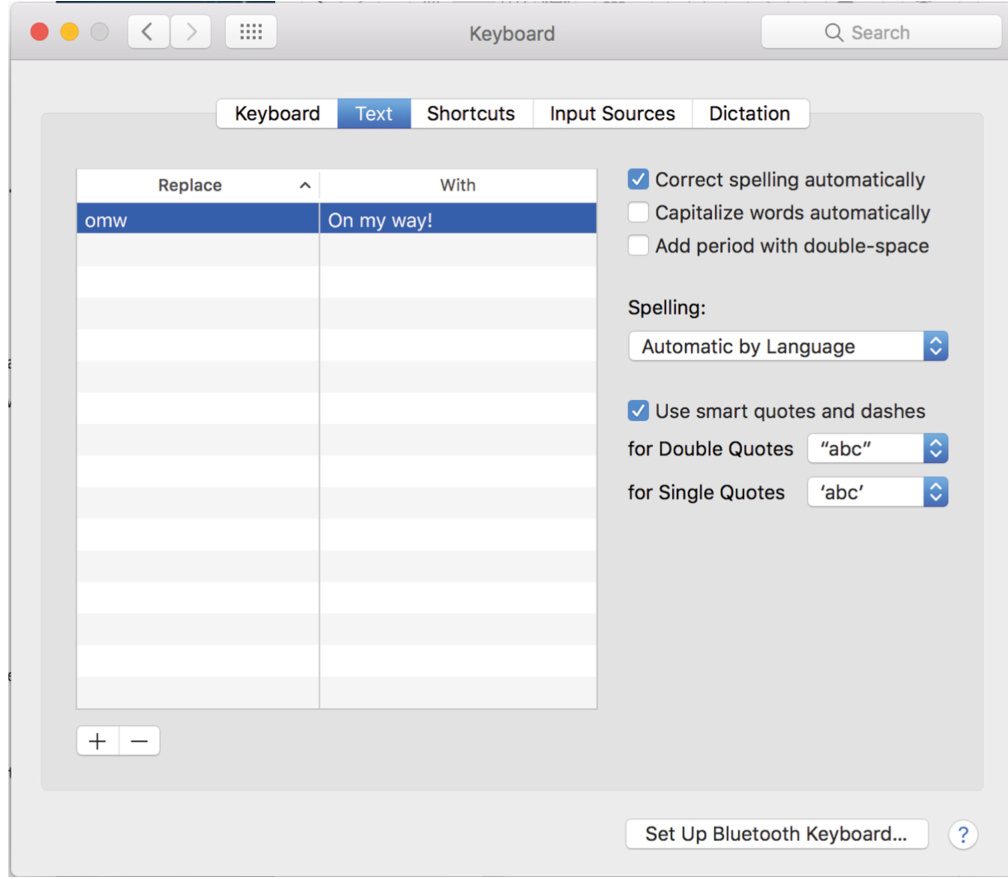

例如,在 Firefox 的键盘文本首选项对话框中,用于控制拼写检查、自动大写和自动添加句号的三个复选框被分组(见图 2.4),并且它们与其他控件以及一个表格控件一起分组。图形设计专家建议使用邻近性来避免视觉杂乱(Mullet 和 Sano,1994),减少添加不用于演示的数据的浪费墨水或像素(Tufte,2001),并减少实现它所需的代码量。

图 2-4 在 Firefox 的键盘文本首选项对话框中,控件使用接近性原则分组,没有使用分组框和边框。

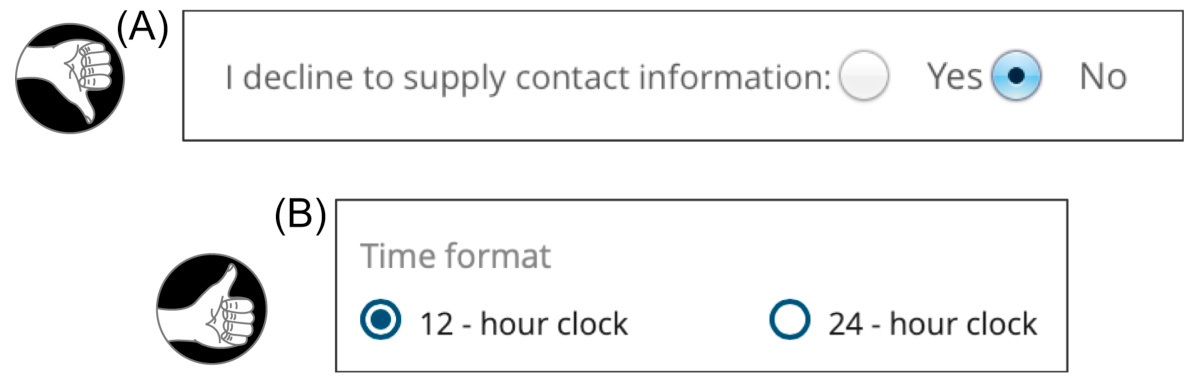

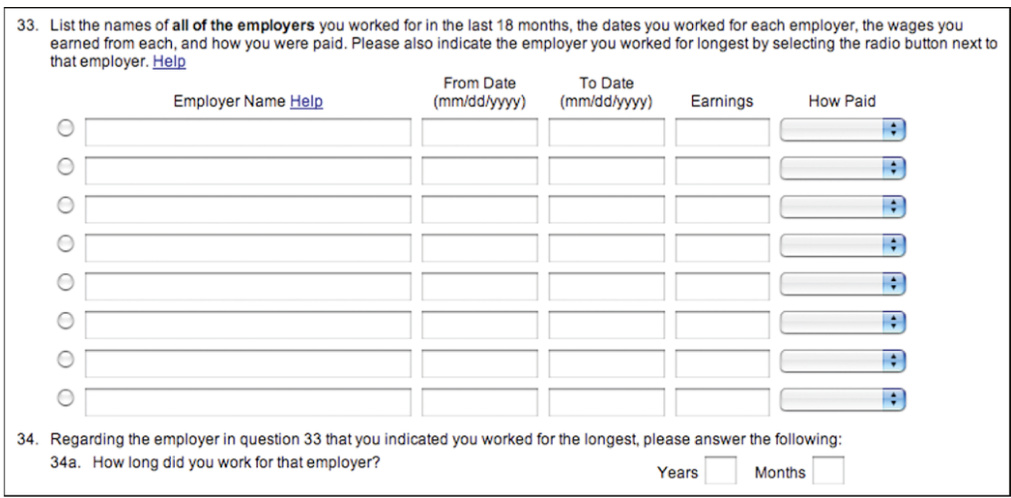

接近性也影响着对控件标签的感知。标签与所标记项目之间的空间过大,人们就不会将标签与项目联系起来。相反,如果标签与另一个项目靠得太近,人们可能会将其与该项目联系起来,而不是预期的项目。例如,Delta.com(2015 年)表单中单选按钮标签的间距不当很容易导致人们选择错误的按钮(见图 2.5A),而 United.com(2020 年)单选按钮标签的间距清楚地显示了哪个标签对应哪个按钮(见图 2.5B)。

图 2-5 单选按钮标签:(A)放置不当;(B)放置良好。

格式塔原理:相似性

格式塔相似性原理指出了影响我们感知分组的另一个因素:如果其他因素相同,那么相似的物体看起来归属于一组。在图 2-6 中,稍微更大、带“空心”的星星被视为一组。

图 2-6 相似性:如果物体看起来相似,就感觉属于一组

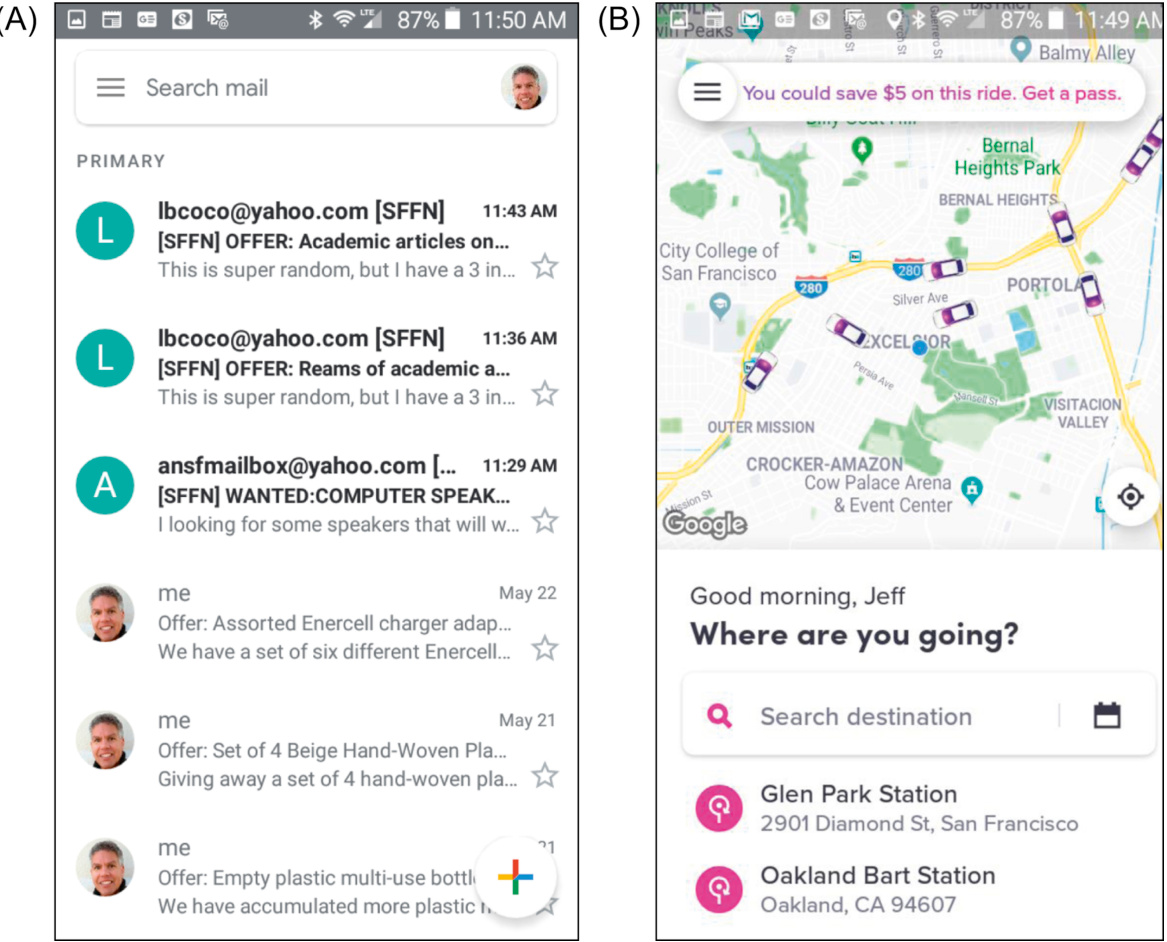

Gmail 使用相似性——粗体与非粗体文本——来帮助用户将未读邮件视为一个与已读邮件不同的独立组(见图 2-7 A)。Lyft 的智能手机应用程序使用相似性——汽车形状——让用户一目了然地看到在其潜在乘客附近的可用司机数量(见图 2-7 B)。

图 2-7 相似性被使用: (A) Gmail 用于使未读邮件与已读邮件区分开来,(B) Lyft 用于提供可用行程的快速概览。

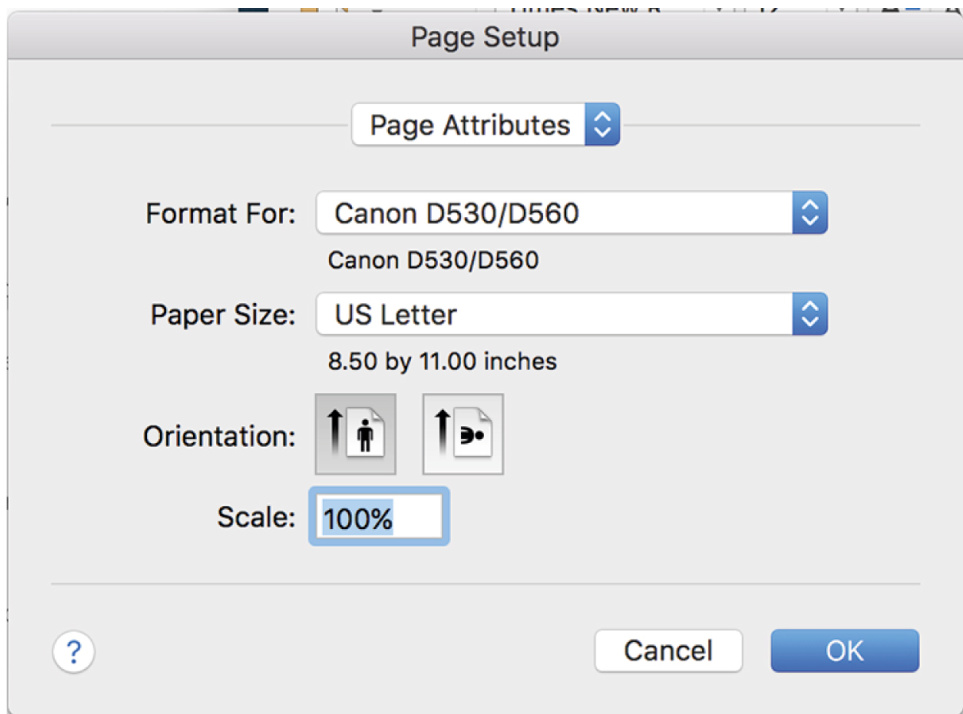

MacOS 应用程序中的页面设置对话框同时使用相似性和邻近性来传达分组(见图 2-8)。两个非常相似且紧密排列的方向设置旨在显得分组。这两个菜单虽然不是那么紧密排列,但看起来足够相似,以至于它们显得分组,即使这可能不是有意为之的。取消和确定按钮被放在一起,远离其他所有东西。即使没有分隔线,它们也会显得是一个组。

图 2-8 Mac OS 页面设置对话框。相似性和邻近性用于对设置和控制进行分组。

格式塔原则:连续性

上述两个格式塔原理都与我们试图给对象分组的倾向相关,另外几个格式塔原理则与我们的视觉系统试图解析模糊或者填补遗漏来感知整个物体的倾向相关。第一个是连续性原理:我们的视觉倾向于感知连续的形式而不是离散的碎片。

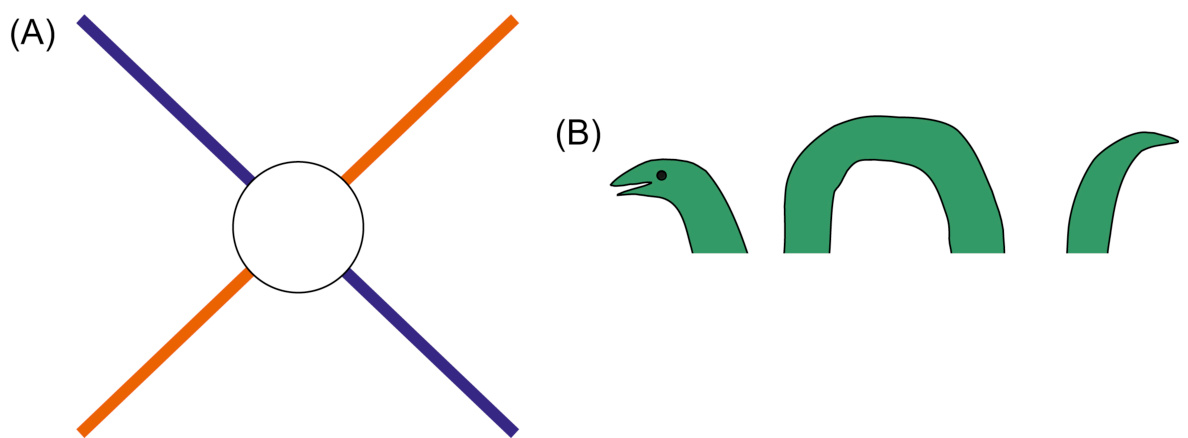

For example, in Fig. 2.9A, we automatically see two crossing lines —one blue and one orange. We don’t see two separate orange segments and two separate blue ones, and we don’t see a blue-andorange V on top of an upside-down orange-and-blue V. In Fig. 2.9B, due to the vertical alignment of the pieces and the fact that they are spaced to match the curvature of the visible pieces, we see a sea monster in water, not three pieces of one. If we misaligned the pieces or spaced the pieces further than the curvature suggests, the illusion of continuity would disappear.

例如,在图 2-9A 中,我们自动看到了一蓝一橙两条交叉的线。我们看到的不是两段橙色线和两段蓝色线,也不是一个左蓝右橙的 V 形位于一个左橙右蓝的倒 V 形之上。在 B 图中,我们看到的是一只水中的海怪,而不是一只海怪的三段身体。如果我们错位部件或使部件间距大于曲线所暗示的,连续性错觉就会消失。

图 2-9 连续性:人类视觉倾向于看到连续的形式,必要时甚至会填补遗漏

在图形设计中,使用了连续性原理的一个广为人知的例子就是 IBM 的标志。它由非连续的蓝色块组成,但一目了然,很容易就能看到三个粗体字母,就像透过百叶窗看到的效果(见图 2-10)。

图 2-10 IBM 公司的标志使用了连续性原理使非连接的色块形成字母

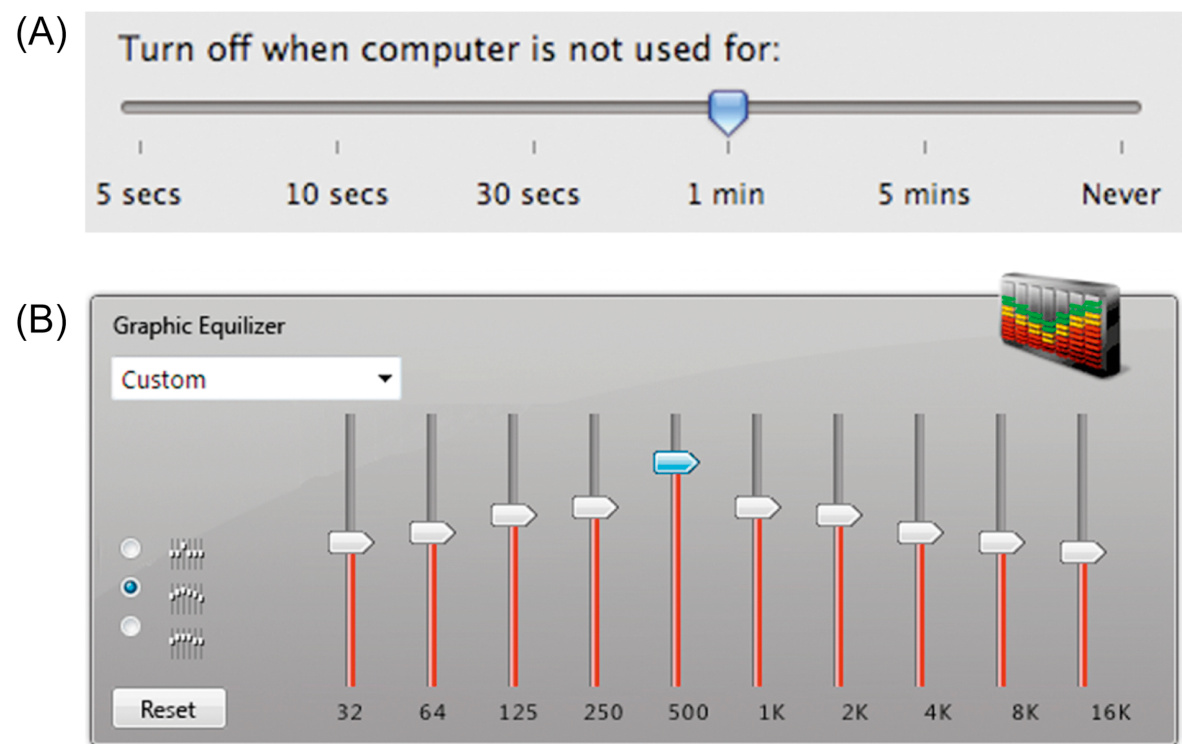

Slider controls are a user-interface example of the Continuity principle. We see a slider as depicting a single range controlled by a handle that appears somewhere on the slider, not as two separate ranges separated by the handle (see Fig. 2.11A). Even displaying different colors on each side of a slider’s handle doesn’t completely “break” our perception of a slider as one continuous object, although ComponentOne’s choice of strongly contrasting colors (gray vs. red) certainly strains that perception a bit (see Fig. 2.11B).

滑动条控件是使用了连续性原理的一个用户界面示例。滑动条表示一个范围,我们看到的是滑动条某个位置上有一个“被控制”的滑块,而不是由滑块分隔成的两个不同区间(见图 2-11A)。即使将滑块的两端的滑动条显示成不同颜色,也不会完全“打破”我们对滑动条是一个连续整体的感知,尽管 ComponentOne 选择使用强烈反差的颜色(灰色与红色)肯定会稍微影响人们连续性的感知(见图 2-11B)。

图 2-11 连续性:我们看到滑块是一个带有手柄的单一插槽,而不是两个由手柄分隔的插槽:(A) Mac OS 和(B) ComponentOne。

格式塔原则:闭合性

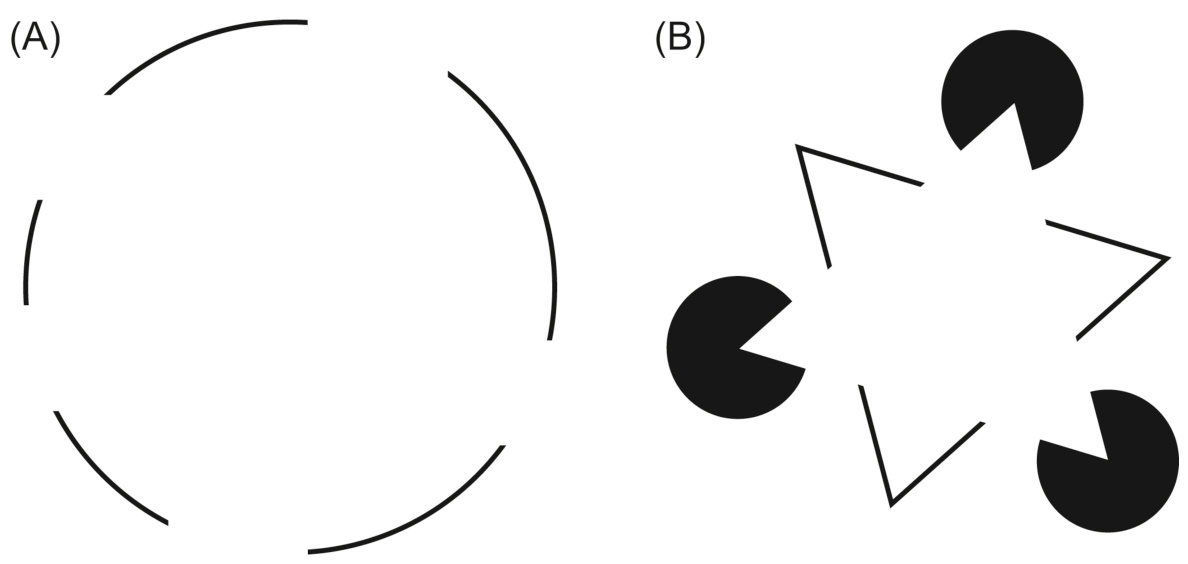

与连续性相关的是格式塔的闭合原则:我们的视觉系统会自动尝试闭合开放的图形,使它们被视为整体对象,而不是单独的碎片。因此,我们感知图 2-12A 中的不连贯的弧线为一个圆。

图 2-12 闭合:人类视觉倾向于看到完整的物体,即使它们是不完整的。

我们的视觉系统强烈倾向于看到物体,以至于它能将一个完全空白的区域解析成一个物体。我们能将图 2-12B 中的形状组合感知为一个白色三角形、另一个三角形和三个黑色圆形叠加在一起,即使画面实际上只有三个 V 形和三个黑色的吃豆人。

封闭性原理经常被应用于图形用户界面(GUI)。例如,GUI 经常用叠起的形式表示对象的集合,例如文档或者消息(见图 2.13)。仅仅显示一个完整的对象和其“背后”对象的一角就足以让用户感知到由一叠对象构成的整体。

图 2.13 展示了桌面图标堆叠物体的闭合原则:部分可见的对象被视为整体。

格式塔原则:对称性

关于我们感知物体的第三个事实是格式塔原则,德语中称为“prägnanz”,字面意思是“良好的图形”,但通常翻译为简单或对称。它指出我们倾向于以减少复杂性的方式解析复杂场景。我们视觉场中的数据通常有多种可能的解释,但我们的视觉会自动组织和解释数据以简化它并赋予对称性,使其更容易理解。

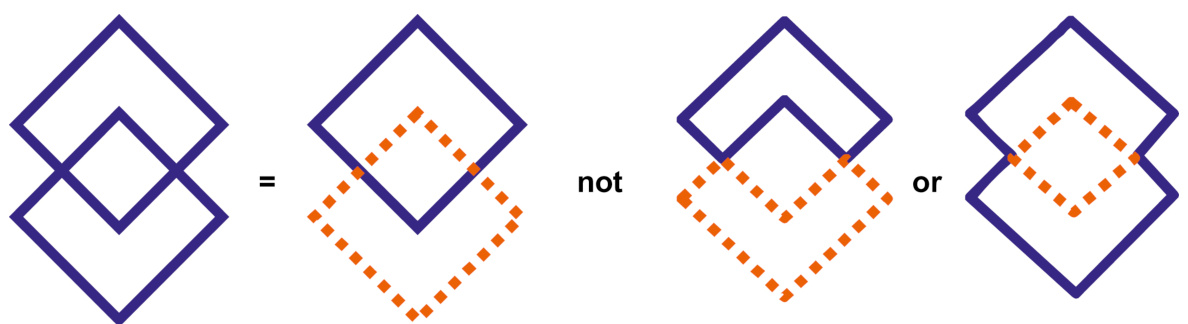

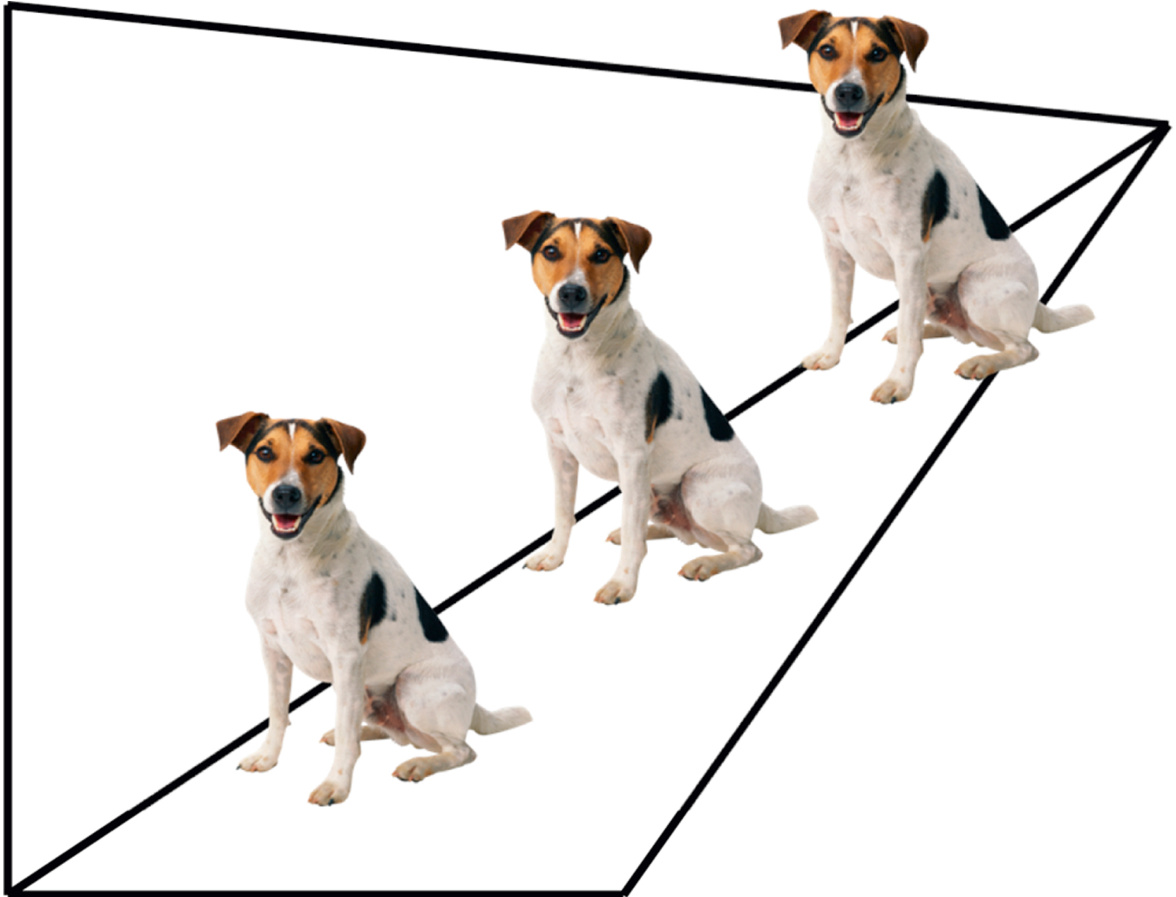

For example, we see the complex shape on the far left of Fig. 2.14 as two overlapping diamonds, not as two touching corner bricks or a pinch-waist octahedron with a square in its center. A pair of overlapping diamonds is simpler than the other two interpretations shown on the right—it has fewer sides and more symmetry than the other two interpretations.

例如,我们将图 2.14 最左侧的复杂形状看作两个重叠的菱形,而不是两块顶部对接的隅砖或者一个中心为小四方形的细腰八边形。一对叠加的菱形比其他两个解释更简单,它的边更少并且比另外两个解析更对称。

图 2.14 对称性:人类视觉系统试图将复杂场景解析为简单对称形状的组合。

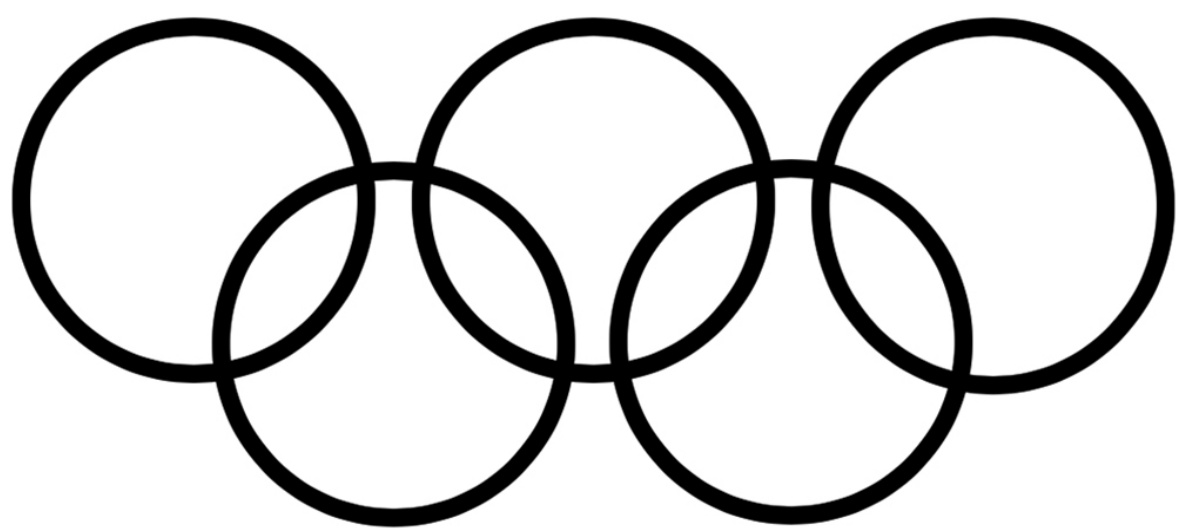

对称原则也预测我们会看到图 2.15 是五个重叠的圆环,而不是一堆相互连接的弧线。

FIGURE 2.15 Symmetry predicts that people will perceive this figure as five overlapping rings.

图 2.15 对称性预测人们会将这个图形感知为五个重叠的圆环。

我们视觉系统对对称性的依赖可以被用来简化复杂信息的扫描和理解。例如,以表格形式——一种对称的数据呈现方式——呈现信息,可以更容易地提取所需信息(参见表 2.1)。

表 2.1

| Student学生 | Quiz2测验 2 | Quiz 4测验 4 | ||

| Fred (B)弗雷德(B) | 95 | 92 | 98 | 90 |

| Susan H.苏珊·H. | 99 | 98 | 97 | 95 |

| Sergei L. | 83 | 91 | 92 | 88 |

| Hannah N. | 75 | 87 | 92 | 83 |

格式塔原理:主体/背景

下一个描述我们的视觉系统如何组织数据的格式塔原理是主体/背景原理,它指出我们的大脑将视觉区域分为主体和背景。主体包括一个场景中占据我们主要注意力的所有元素,其余的则是背景。

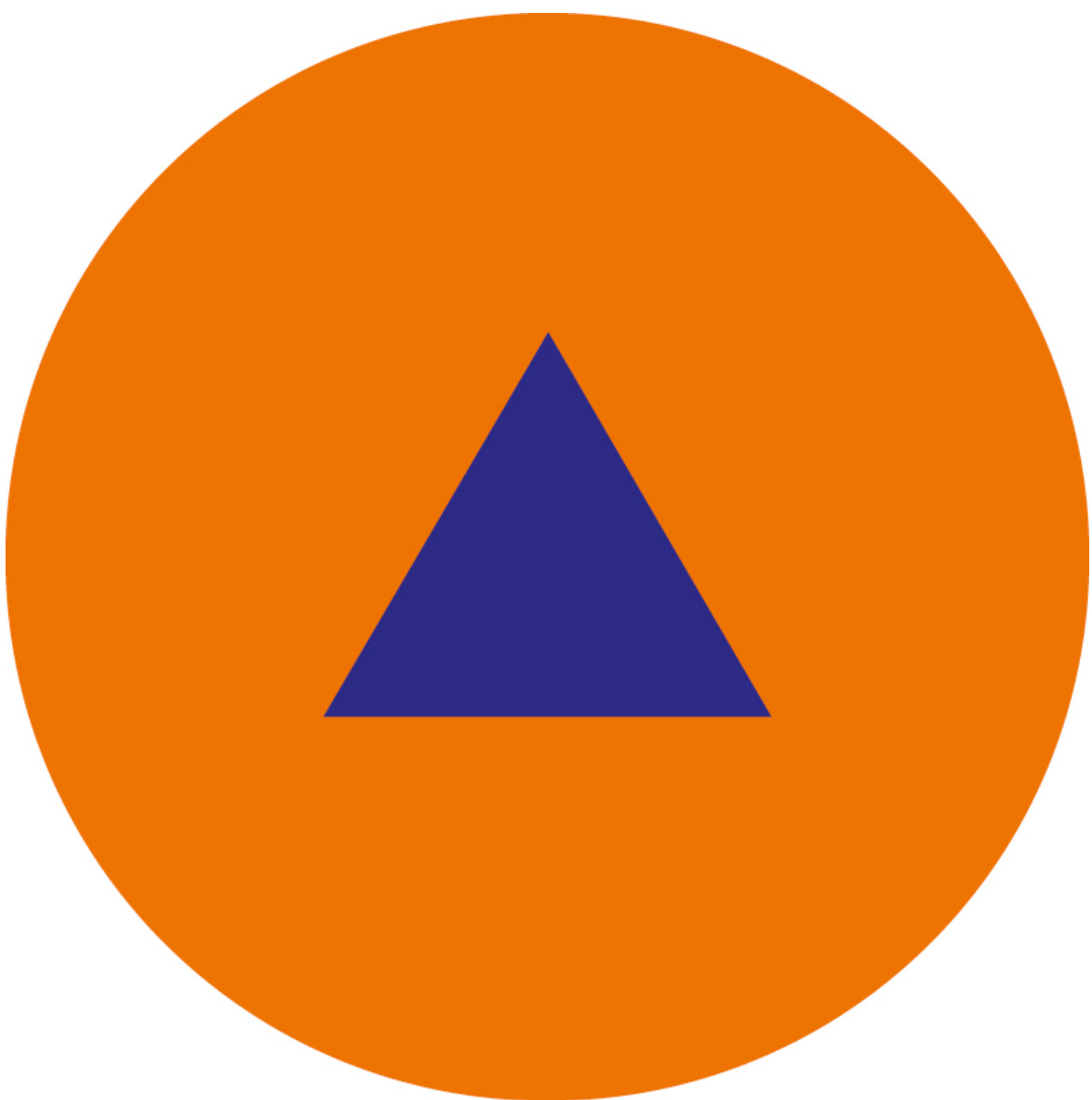

主体/背景原理也说明场景的特点会影响视觉系统对场景中的主体和背景的解析。例如,当一个小物体或者色块与更大的物体或者色块重叠时,我们倾向于认为小的物体是主体而大的物体是背景(见图 2-16)。

图 2-16 主体/背景:当物体重叠时,我们把小的那个看成是背景之上的主体

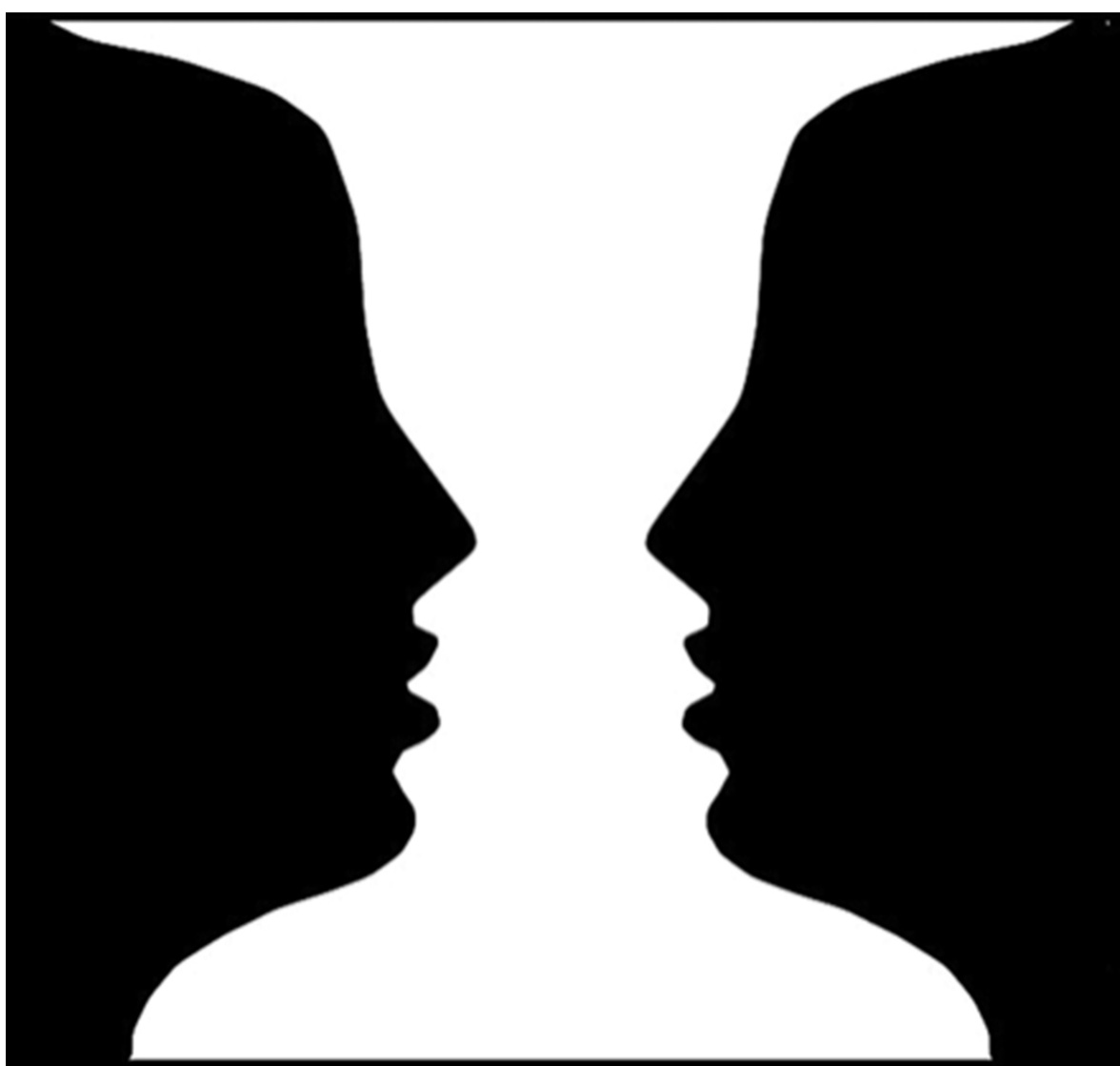

然而,我们对图形与背景的感知并非完全由场景特征决定。它还取决于观察者的注意力焦点,如图 2.17 所示。这是一个花瓶还是两张脸?

FIGURE 2.17 Vase or faces? Perception of figure versus ground depends on a viewer’s focus of attention.

图 2.17 瓶子还是人脸?图形与背景的感知取决于观察者的注意力焦点。

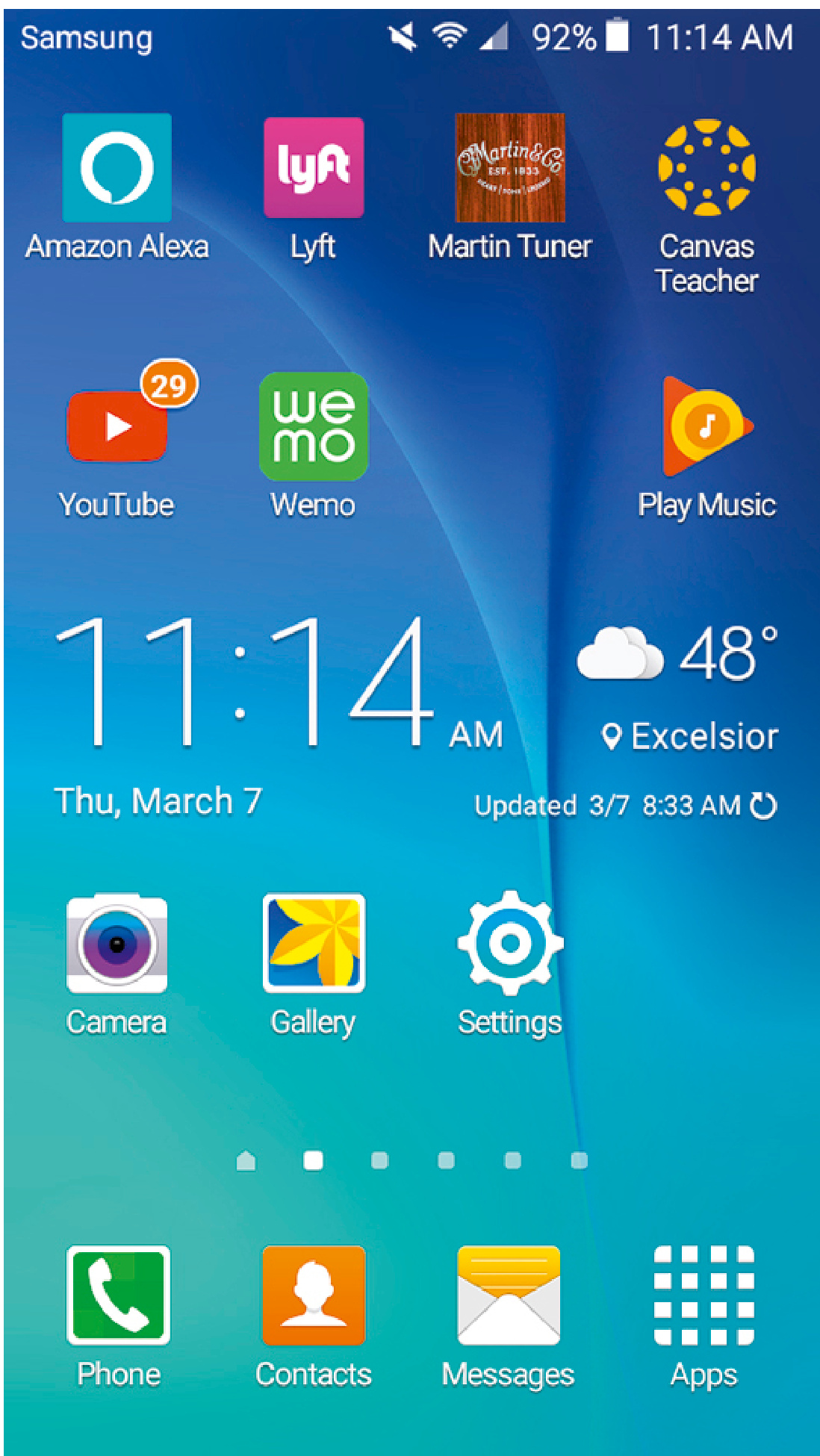

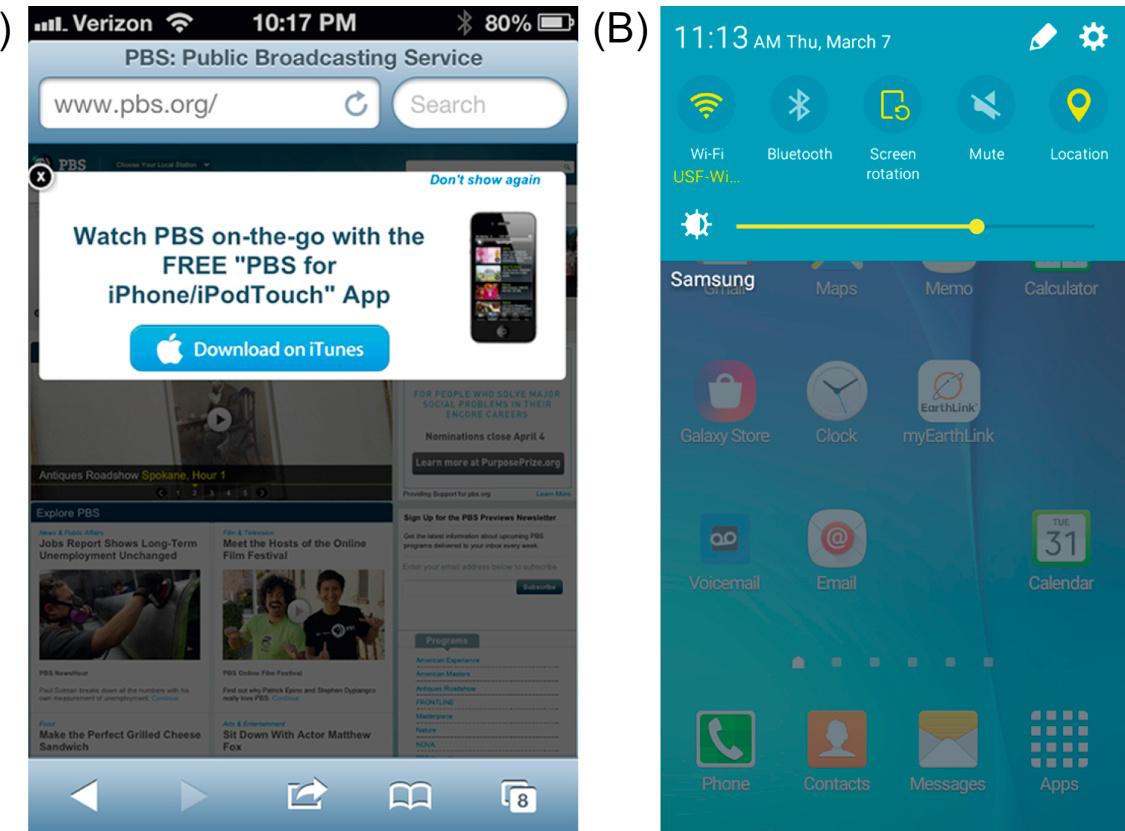

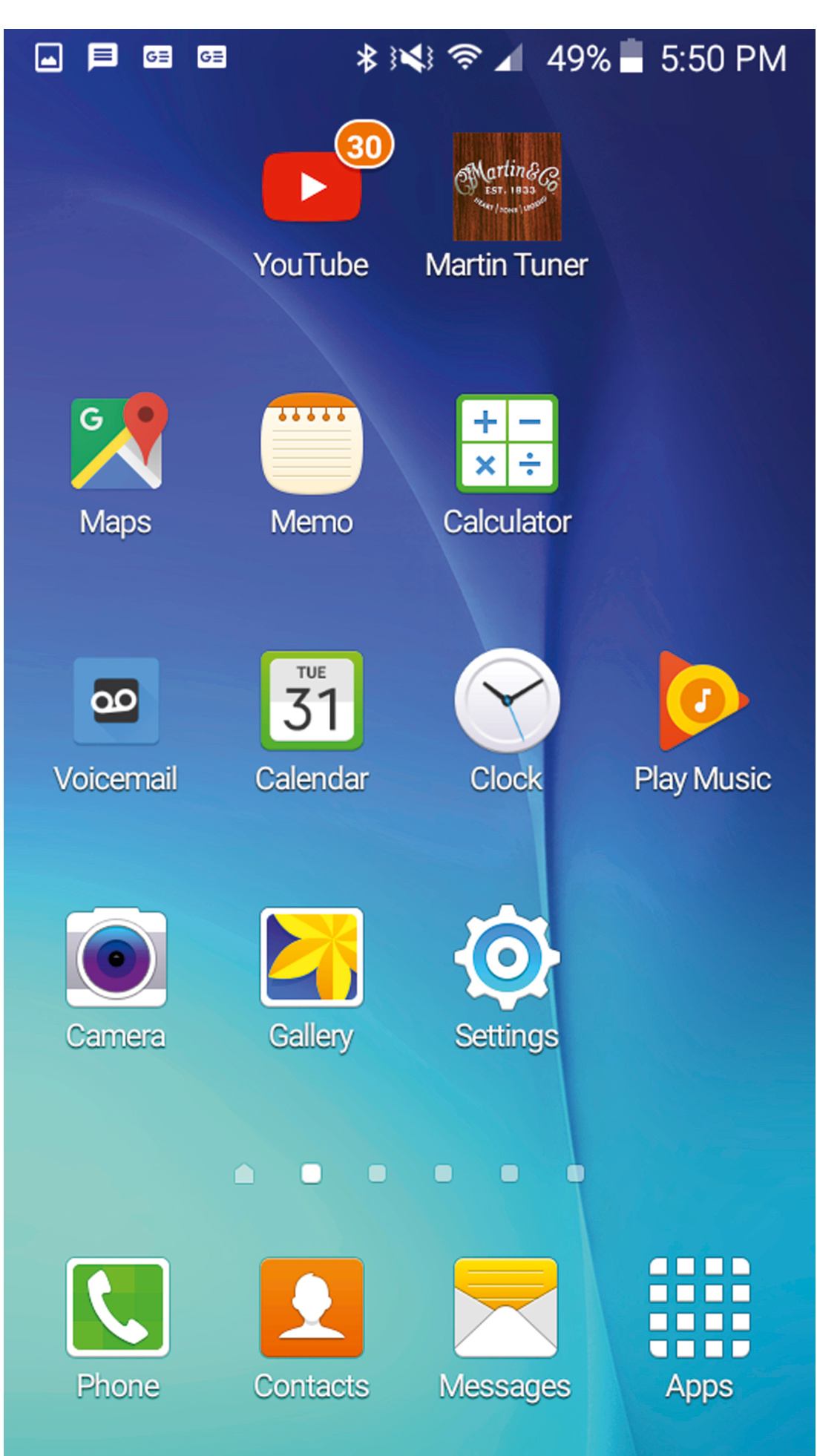

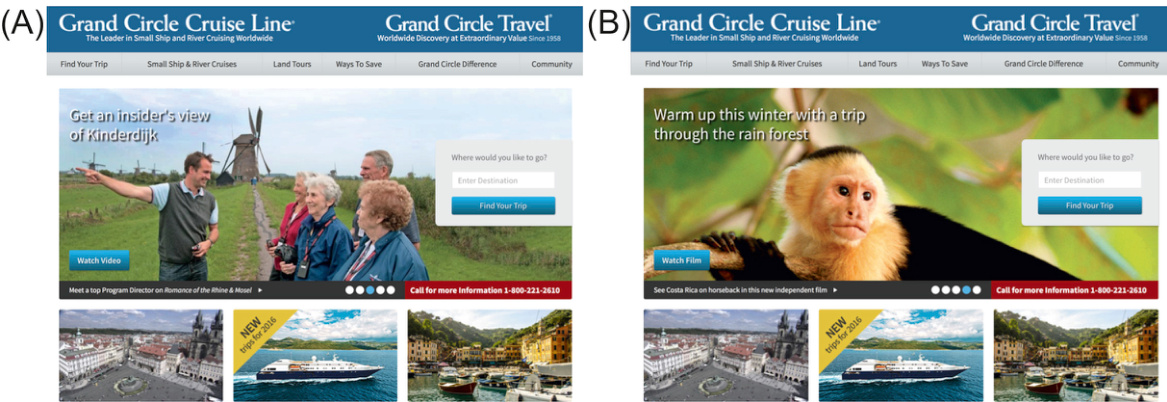

在用户界面和网页设计中,主体/背景原理经常用来在主要显示内容的“下方”放置印象诱导的背景。背景可以传递信息,例如用户在系统中的位置,就像 Android 桌面在图 2.18 中,或者它可以建议一个主题、品牌或情绪来解释内容。

图 2.18 图形/背景在手机、平板电脑和计算机中用于显示设备的“主页”或“桌面”屏幕。

图形/背景也常用于在其它内容上弹出信息。原本是图形——用户注意力的焦点——暂时成为新信息的背景,新信息短暂地作为新的图形出现(见图 2.19)。这种方法通常比暂时用新信息替换旧信息更好,因为它提供了上下文,有助于人们了解他们在交互中的位置。

图 2.19 图形/背景可用于显示“覆盖”页面内容的信息:(A)PBS. Org 移动网站的号召性用语和(B)Android 设置下拉菜单。

格式塔原理:共同命运

前面 6 个格式塔原理针对的是静态(非运动)图形和对象,最后一个格式塔原理一共同命运,则涉及运动的物体。共同命运原理与接近性原理和相似性原理相关,都影响我们所感知的物体是否成组。共同命运原理指出一起运动的物体被感知为属于一组或者是彼此相关的。

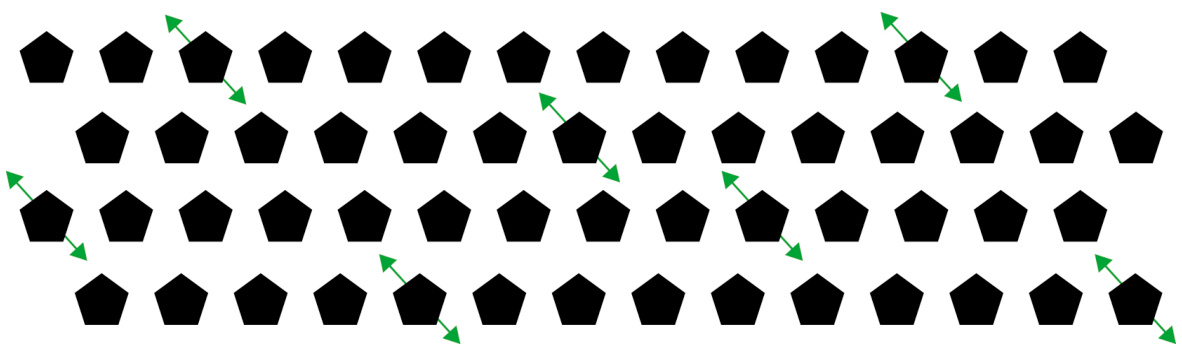

例如,在数十个五边形中,如果其中 7 个同步地前后摇摆,人们将把它们看成相关的一组,即使这些摇摆的五边形互相之间是分离的,而且看起来与其他的也没什么不同(见图 2.20)。

图 2.20 共同命运:一起运动的物体看起来是一组的或者相关的

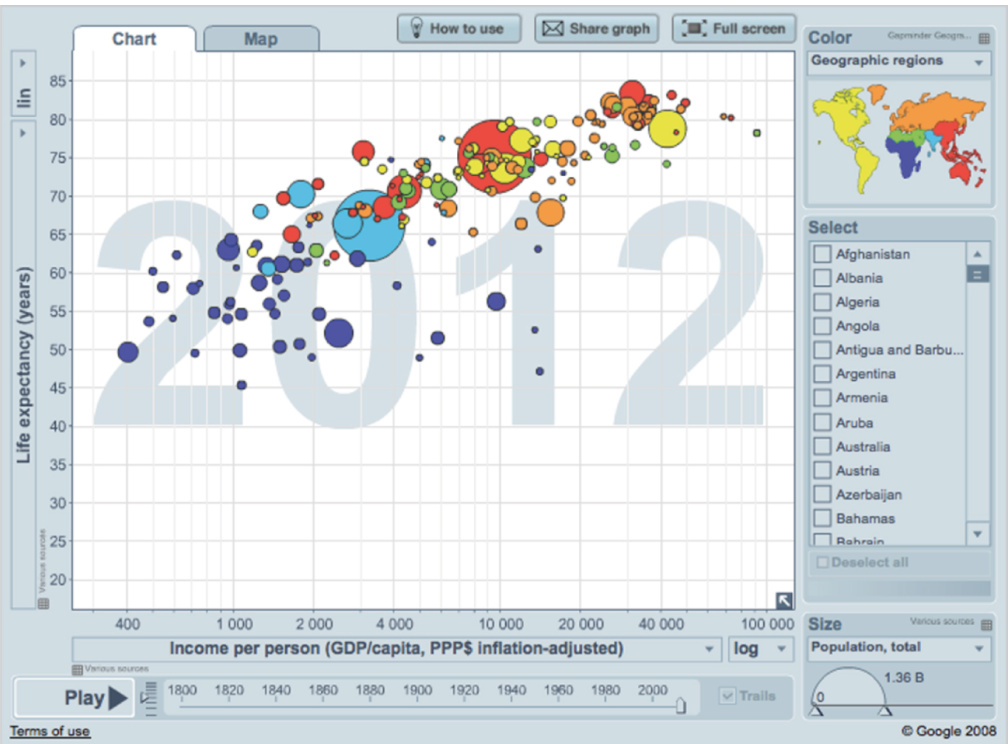

共同的运动暗示共同的历程,在一些动态模拟中可用以展示不同实体的关系。例如,GapMinder 的图像中代表国家的点模拟经济发展的多个因素随着时间变化而变化,一同运动的国家具有相同的发展历史(见图 2.21)。

图 2.21 共同命运:GapMinder 动画模拟点显示哪些国家具有相似的发展历史(详情、动画和视频,请访问 Gapminder.org)。

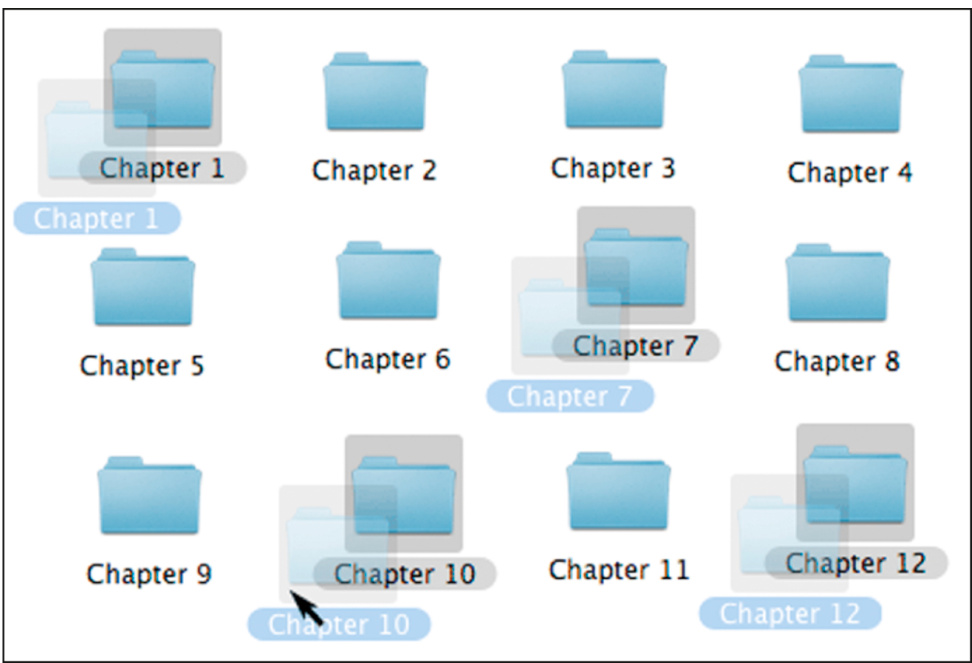

将格式塔原理综合起来

当然,在现实世界的视觉场景中,各种格式塔原理不是孤立的,而是共同起作用的。例如,一个典型的 MacOS 桌面通常可以示范之前提到 7 个原理中的 6 个(除了共同命运原理):接近性原理、相似性原理、连续性原理、封闭性原理、对称性原理以及主体/背景原理(见图 2.22)。在典型的桌面中,当用户一次选取多个文件或者目录并拖曳到新的位置时,就用到了共同命运原理(还有相似性原理)(见图 2.23)。

图 2.22 除了共同命运原理,所有的格式塔原理在 MaCOS 桌面的这一部分都发挥了作用

图 2.23 相似性原理和共同命运原理:当用户拖曳选中的文件夹时,共同的高亮和运动使得所有被选中的文件夹看起来是一组的

同时用上所有的格式塔原理时,设计可能会导致无意产生的视觉关系。推荐的办法是,在设计一个显示之后,使用每个格式塔原理(接近性原理、相似性原理、连续性原理、封闭性原理、对称性原理、主体/背景原理以及共同命运原理)来考量各个设计元素之间的关系是否符合设计的初衷。

重要要点

为了方便参考,本章介绍了格式塔视觉感知原则,这些原则与用户界面设计最相关:

• Proximity: Objects near each other (relative to other objects) appear grouped, while those farther apart do not.

• 接近性:彼此靠近的物体(相对于其他物体)看起来是分组的,而彼此距离较远的则不是。

• Similarity: Objects that look similar appear grouped.

• 相似性:看起来相似的物体会被归为一组。

• Continuity: Our visual perception is biased to perceive continuous forms rather than disconnected segments.

• 连续性:我们的视觉感知倾向于感知连续的形态而非分离的片段。

• Closure: Our visual system automatically tries to close figures that are open so they are perceived as whole objects rather than separate pieces.

• 闭合性:我们的视觉系统会自动尝试闭合开放的图形,使它们被视为整体对象而非单独的碎片。

• Symmetry: Our visual system parses complex scenes in a way that reduces their complexity by recognizing symmetries in the scene.

• 对称性:我们的视觉系统通过识别场景中的对称性来解析复杂场景,从而降低其复杂性。

• Figure/Ground: Our mind separates the visual field into the figure (the foreground) and ground (the background). • Common Fate: Objects that move together are perceived as grouped or related.

• 图形/背景:我们的头脑将视觉领域分为图形(前景)和背景(地面)。 • 共命运:一起移动的物体被视为分组或相关。

第三章:我们探索和利用视觉结构

摘要

人们使用视觉结构来帮助他们从所见中提取信息。因此,以结构化方式显示信息的交互式系统使人们更容易、更快地提取所需信息。本章提供了结构化与非结构化信息显示的示例。例如,在呈现信息时,一个重要的目标是提供视觉层次结构——信息的排列方式将其分为不同的部分和子部分,突出显示部分以清楚地标识其内容,并比低级部分更强烈地呈现高级部分。这允许人们在扫描信息时,能立即将与其目标相关的内容与不相关的内容分开,并专注于相关信息。

关键词

Credit card numbers; Online forms; Repetition; Search results; Social security numbers; Tables; Telephone numbers; Visual hierarchy; Visual structure

信用卡号码;在线表单;重复;搜索结果;社会保障号码;表格;电话号码;视觉层次结构;视觉结构

第二章展示了我们的视觉系统如何根据视觉感知的格式塔原则来感知结构。感知环境中的结构有助于我们快速理解物体和事件。第二章还解释了,当人们浏览软件或网站时,他们不会仔细检查屏幕并阅读每个字。他们会快速扫描与他们目标相关的信息。本章(1)表明,当信息以简洁、结构化的方式呈现时,人们更容易扫描和理解,并(2)解释了如何最佳地组织信息。

结构化信息更容易浏览

考虑一下对同一机票预定信息的两种呈现方式:一种是松散无结构的文字,另一种是以概述的形式结构化的文字(见图 3-1)。与用松散文字呈现的信息相比,结构化呈现的订票信息能够被更快地浏览和理解。

图 3-1 结构化呈现的航班预定信息更容易浏览和理解

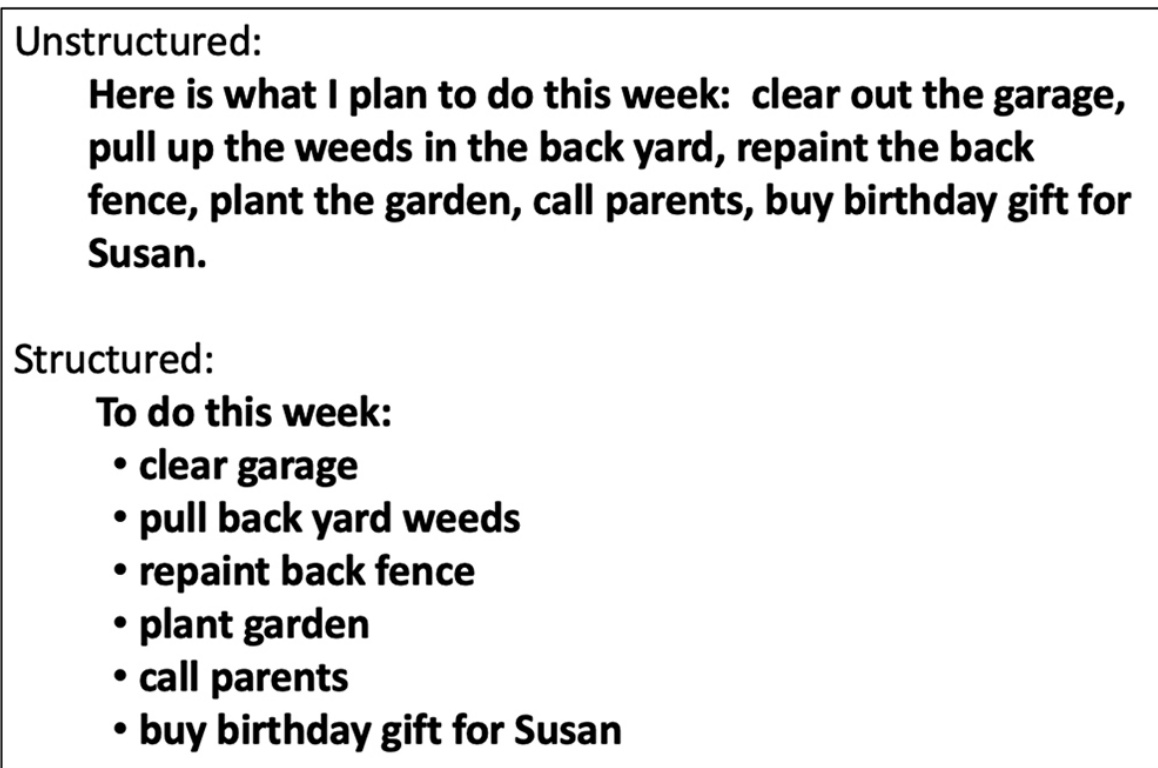

接下来,考虑两种展示列表的方式。如上所述,第一种是不结构的散文文本;第二种是使用项目符号(见图 3.2)进行结构化。与散文段落相比,项目符号列表更快地扫描和理解。如果列表是编号的,情况也是如此。

图 3.2 结构化(项目符号)列表更容易扫描。

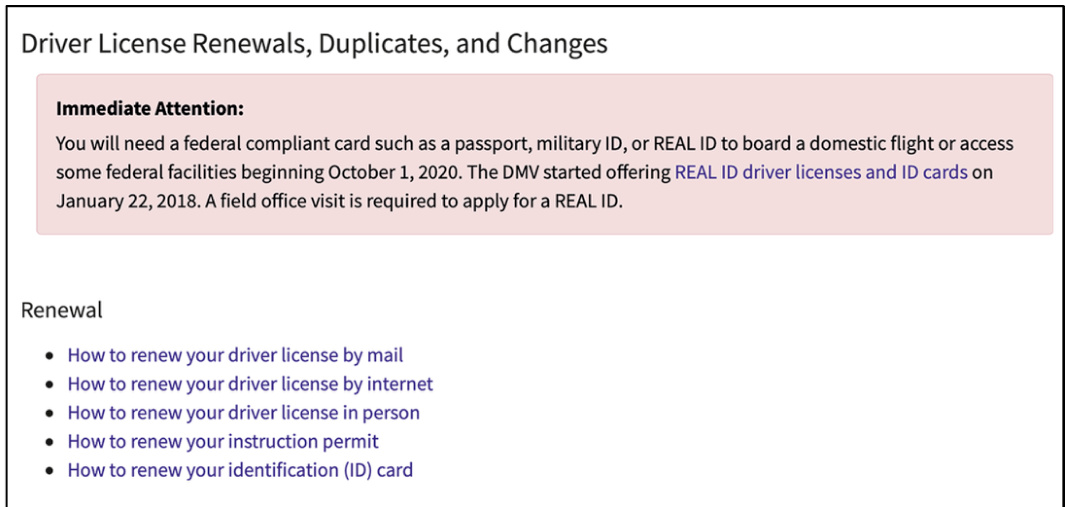

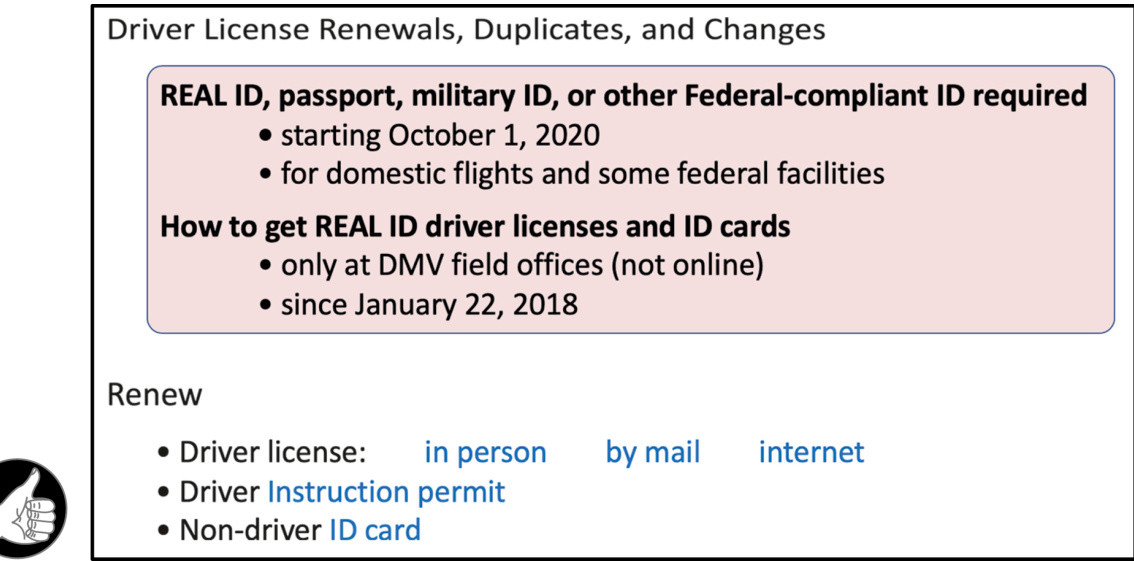

信息呈现越结构化和简洁,人们就越能快速轻松地扫描和理解它。看看加利福尼亚州机动车管理局的“驾照续期、重复和变更”页面(见图 3.3)。即使有项目符号列表,冗长、重复的链接也会让用户放慢速度,并“隐藏”他们需要看到的重要词语。

图 3.3 加利福尼亚州机动车管理局网站的内容页面上,重要的信息被掩埋在散乱重复的文字之中

比较一下这种更简洁、结构化的假设设计,它消除了不必要的重复,并且只将代表选项的词语标记为链接(见图 3.4)。修订版提供了与网站实际页面相同的信息和选项,但更容易浏览。

图 3.4 去掉加利福尼亚州机动车管理局网站内容页面上重复的文字,使用更好的视觉结构。

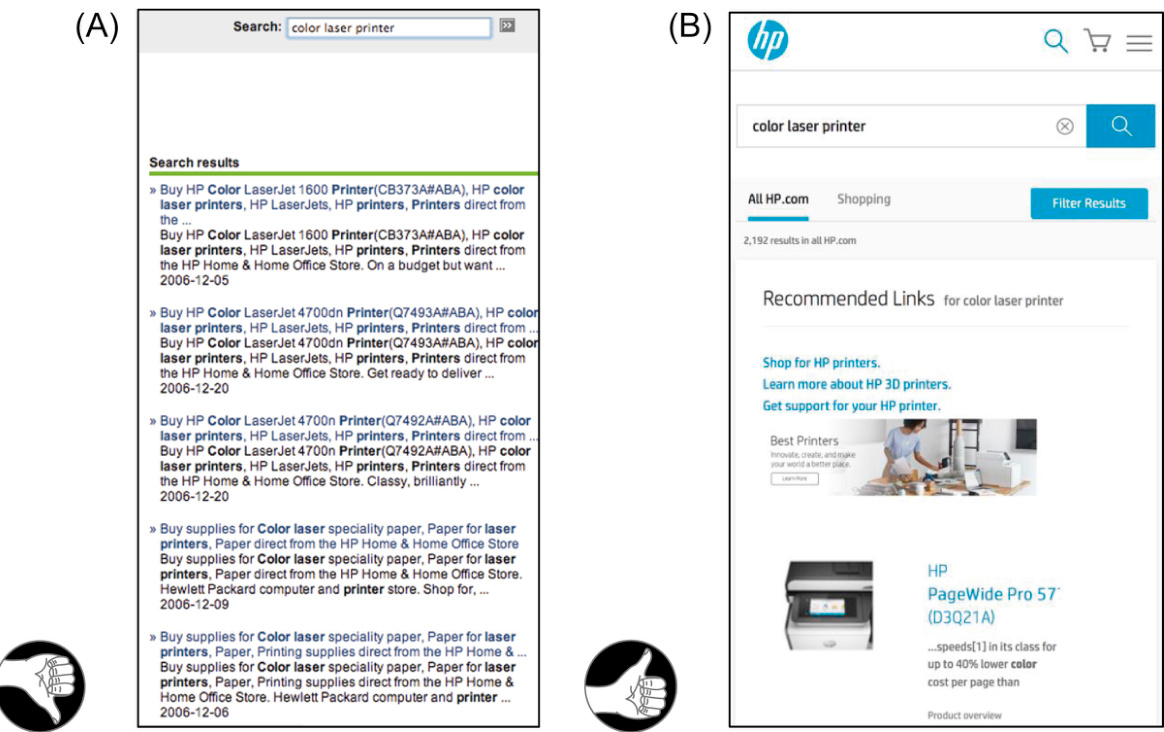

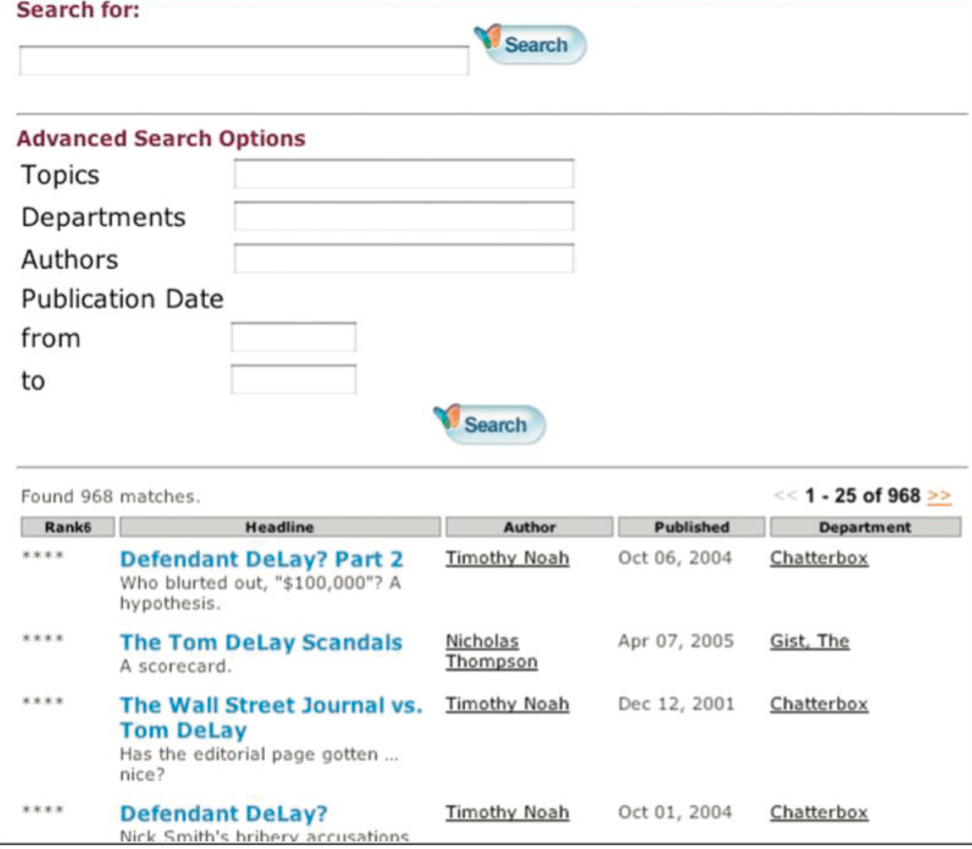

显示搜索结果也是结构化数据并避免重复“噪音”可以提高人们快速浏览并找到他们需要的内容的情况。2006 年,HP.com 的搜索结果包含大量重复的导航数据和每个检索项的元数据,以至于它们毫无用处。最近的 HP 网站消除了重复并结构化结果,使它们更容易浏览且更有用(见图 3.5)。

图 3.5 2006 年,HP.com 的站内搜索呈现重复的、高噪声的结果(A),但后来(2019 年)得到了改进(B)。

当然,要让信息能够被快速地浏览,仅仅把它们变得精炼、结构化和不重复还不够,它们还必须遵从图形设计的规则,第 2 章已经介绍了其中的一些。

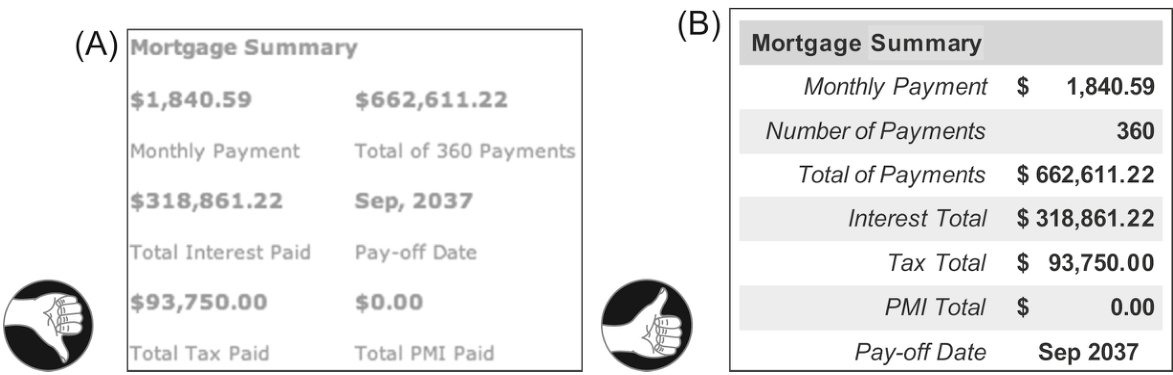

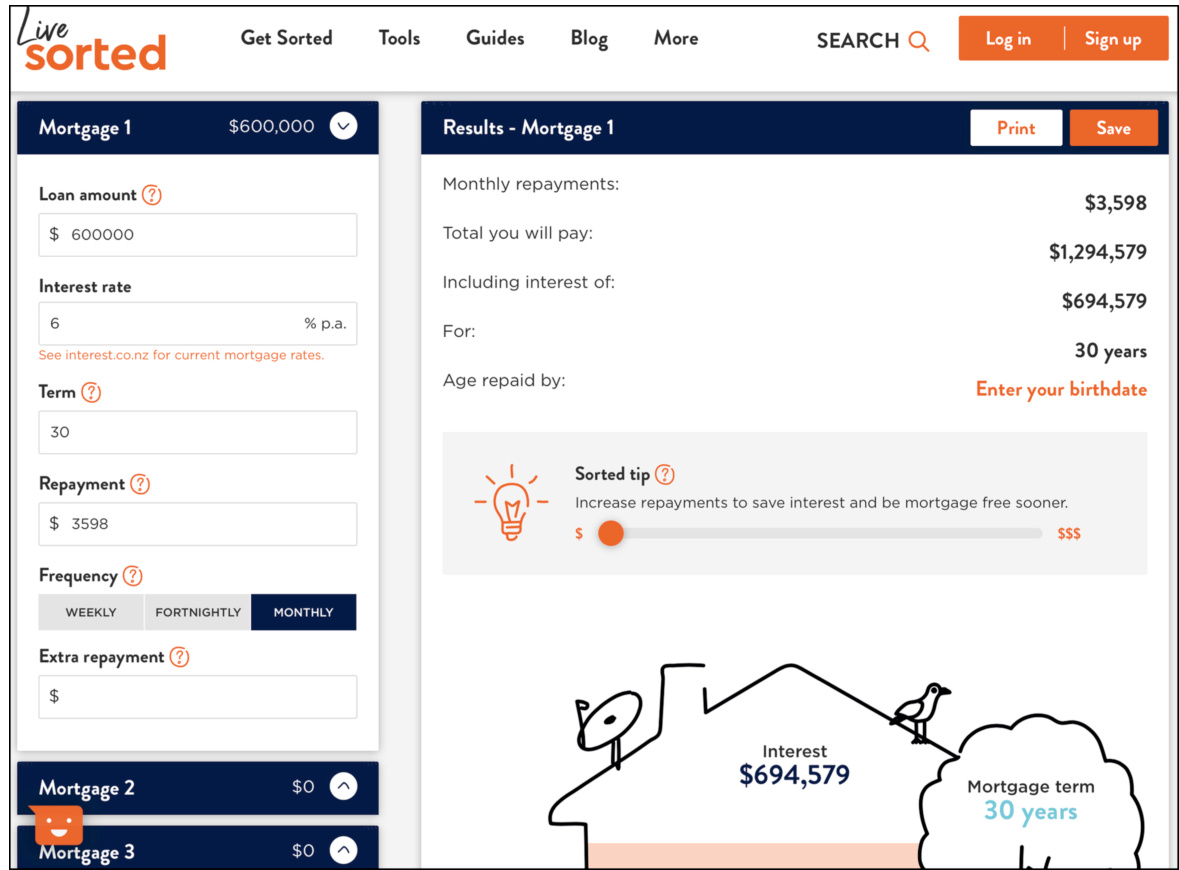

例如,一个房地产网站上的预览版的按揭计算器将其计算结果用表单的形式展示,就违反了至少两条重要的图形设计的规则(见图 3.6A)。其一,人们在线或离线阅读时通常是从上往下,但计算结果的标签却被放置在其结果值的下方;其二,标签和对应的值与下一个值之间的距离一样近,因此标签与其对应的值不能通过接近性(见第 2 章)被感知到是相关的。用户要理解这张按揭计算表格,就得非常费劲地认真检查,慢慢地搞清楚哪个标签对应哪个值。

相比之下,修订后的设计允许用户无需有意识思考就能感知标签与值的对应关系(见图 3.6B)。

图 3.6 (A)软件抵押贷款计算器展示的抵押摘要;(B)一个改进的设计。

视觉层次结构帮助人们找到相关信息

结构化信息展示最常见的方法之一是提供视觉层次结构——一种安排方式:

• 将信息分成不同的部分,并将大部分分成子部分;

• 醒目地标记每个部分和子部分,以便内容能被清晰识别;

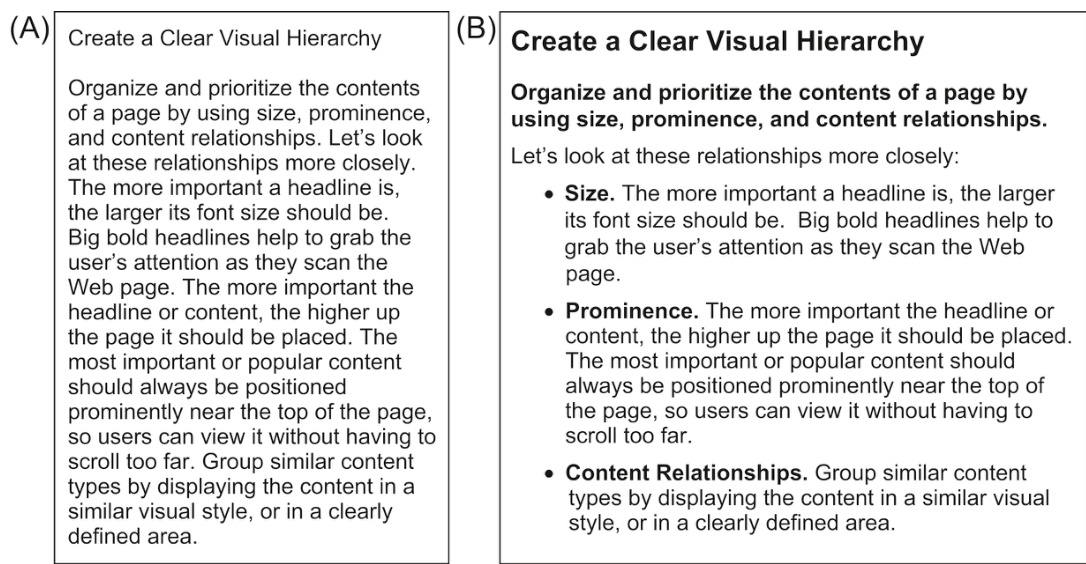

图 3.7 在这些显示中找到关于醒目的建议。散文文本格式(A)迫使用户阅读或浏览所有内容。视觉层次结构(B)让用户跳过不相关的内容,直接找到与他们目标最相关的信息。

将章节和子章节以层次结构呈现,高级别的章节呈现得比低级别的章节更突出。

视觉层次结构使人们在浏览信息时,能够快速区分与目标相关的信息和不相关的信息,并专注于相关信息。他们能更快地找到他们要找的内容,因为他们可以轻松地跳过其他所有内容。

亲自试试。看看图 3.7 中的两个信息显示,找到关于突出显示的信息。在非层次结构显示中,你找到它需要多长时间?

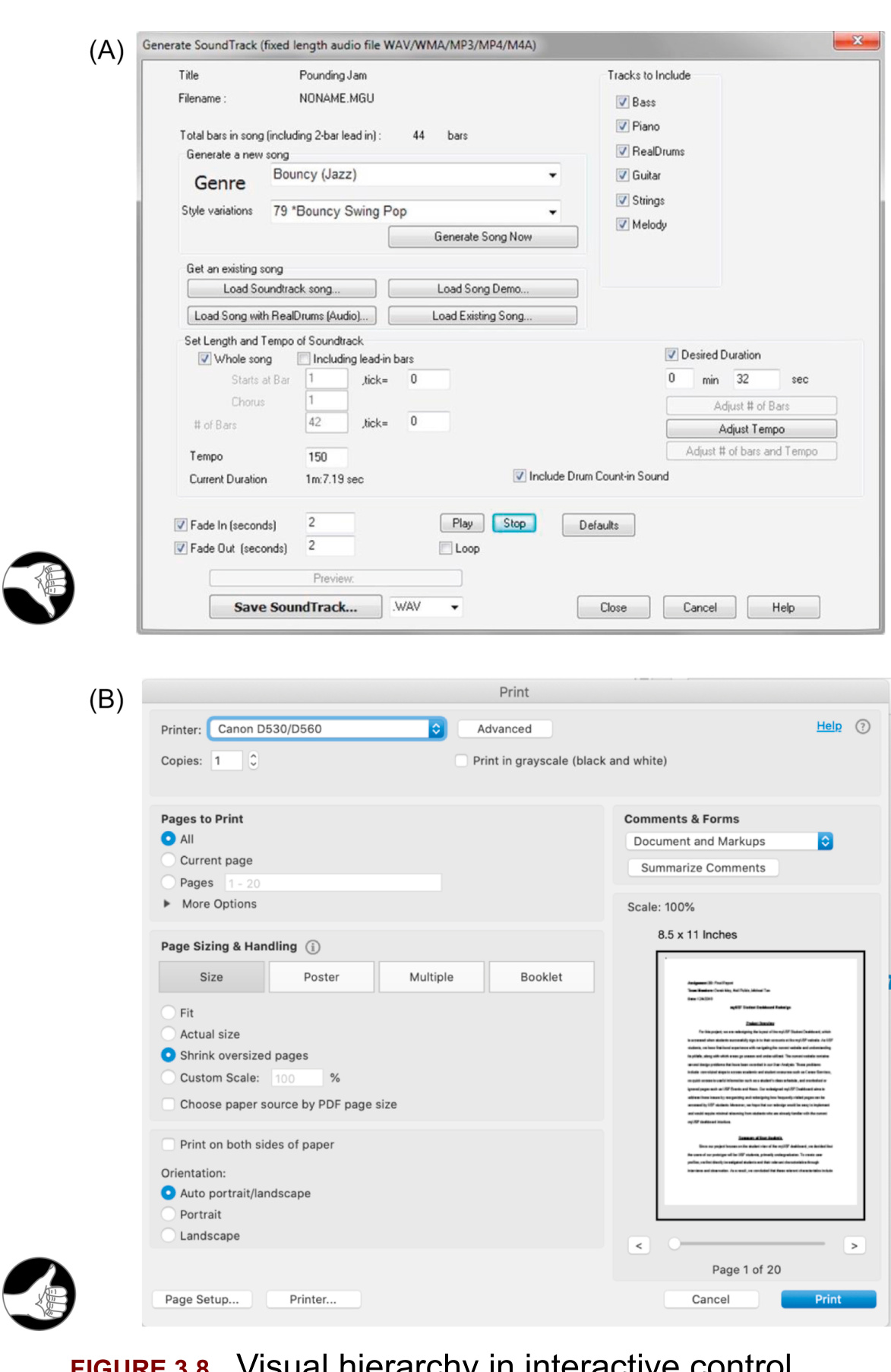

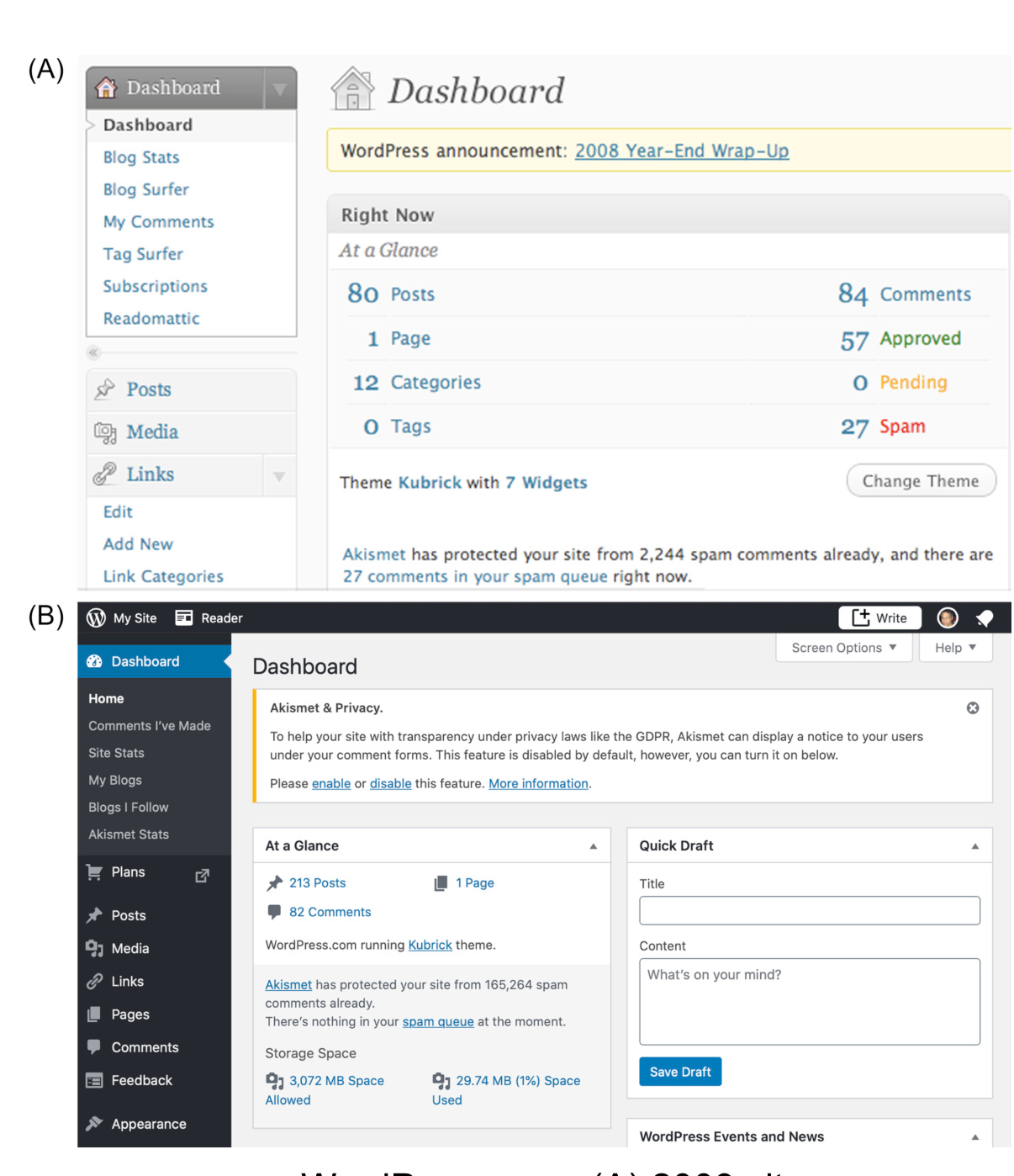

图 3.7 中的示例展示了视觉层次结构在纯文本、只读信息显示中的价值。视觉层次结构在交互式控制面板和表单中同样重要——甚至可能更重要。比较两个不同软件产品的对话框(见图 3.8)。音乐应用 Band-in-a-Box 的“生成音轨”对话框视觉层次结构较差,使用户难以扫描并快速找到设置。相比之下,Adobe Acrobat Pro 的“打印”对话框具有更好的视觉层次结构,因此用户可以快速找到所需的设置。

超越视觉层次结构:信息层次结构

视觉层次结构实际上应该被称为“信息层次结构”,因为其基本设计原则比视觉设计更广泛地适用。使用标题、副标题和其他分组来定义章节和子章节,按层次结构组织信息,甚至可以帮助视障和盲人用户找到他们需要的内容。

panels and forms lets users find settings quickly:

面板和表单使用户可以快速找到设置:

(A) Band-in-a-Box (2017—差) 和 (B) Adobe Acrobat Pro (2019–好)

考虑一个使用屏幕阅读器的盲人用户在图 3.7 中搜索关于“突出性”的信息,或者试图在图 3.8 中显示的对话框中找到特定设置。

对于图 3.7A,盲人用户将不得不指挥他们的屏幕阅读器系统地阅读大部分信息,然后才能到达所需内容,但在图 3.7B 中,信息通过标题分为各个部分,盲人用户可以让他们的屏幕阅读器只读取各个部分的标题,跳过无关部分的内容。这样他们可以更快地找到关于“突出性”的信息。

类似地,使用 Band-in-a-Box 的“生成音轨”对话框(见图 3.8A),视障用户将不得不费力地通过大部分设置来找到他们想要的设置,但使用 Acrobat Pro 的“打印”对话框(见图 3.8B),如果区域标题被标记为标题,他们可以快速找到相关部分,然后在其中查找他们想要的控件。

为了帮助网络开发者和设计师创建可供视障人士使用的信息显示,万维网联盟(W3C)制定了《万维网内容可访问性指南》(WCAG 2.0)(W3C,2008a)。WCAG 2.0 指南建议设计师使用层叠样式表来标记文本部分和子部分,以及屏幕的划分和子划分,并使用适当级别的标题(W3C,2008b)。

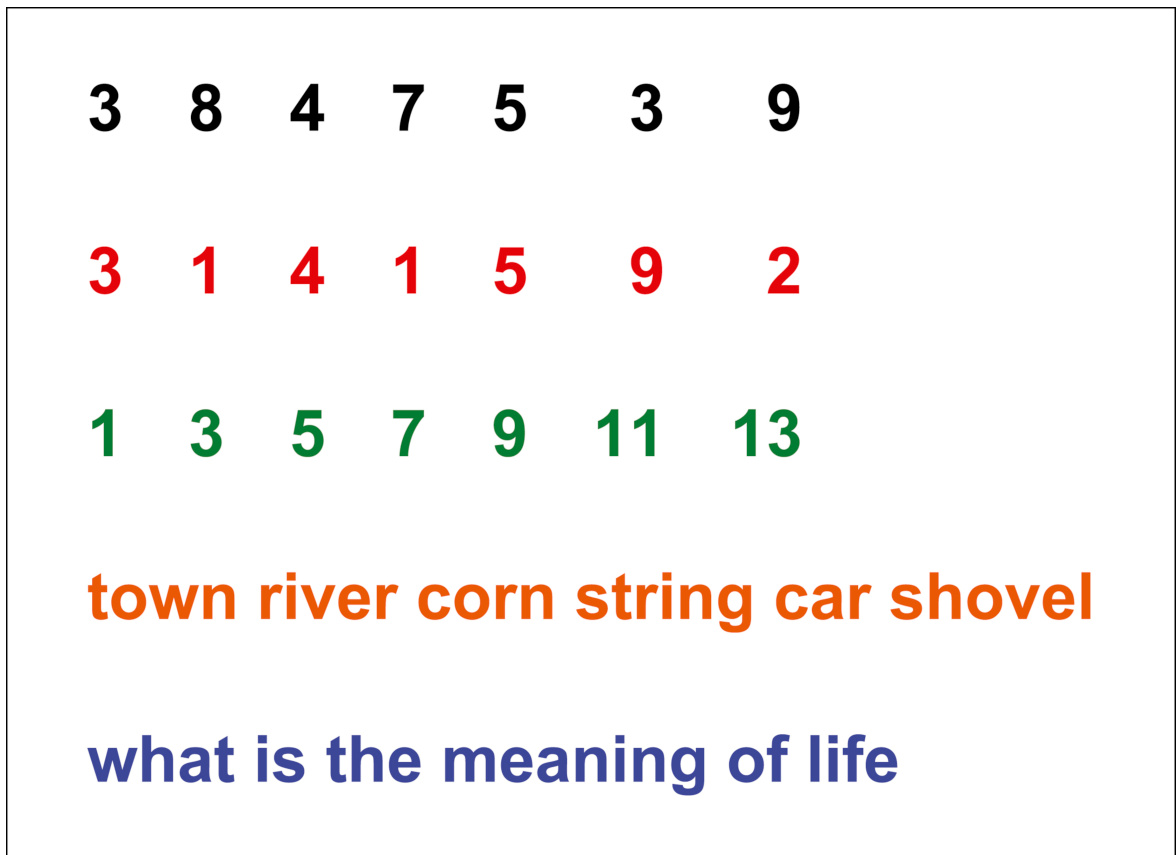

“Chunking” Helps People Scan and Enter Data

“信息块化”帮助人们扫描和输入数据

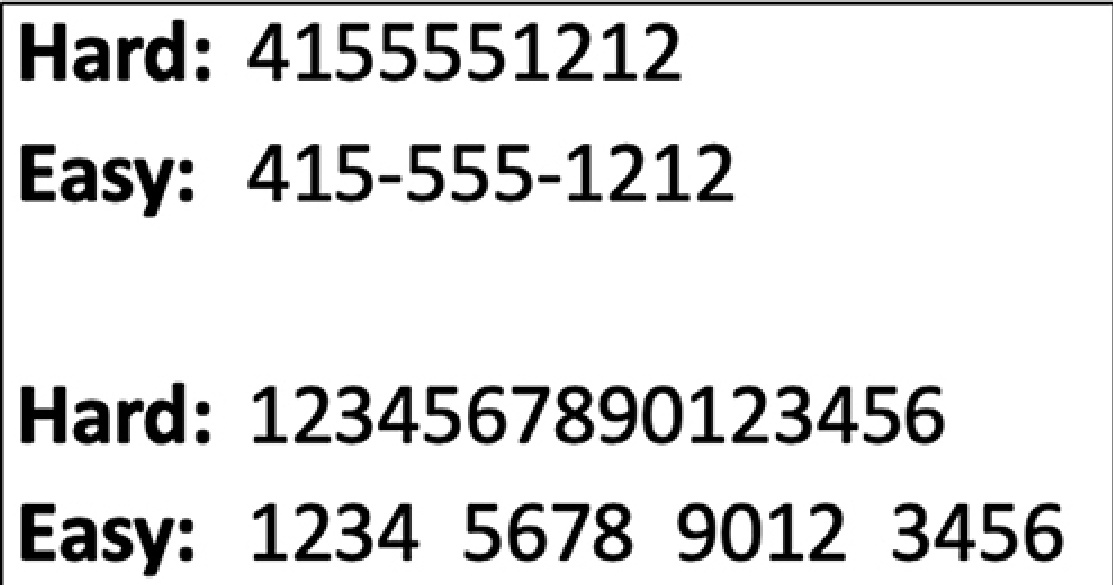

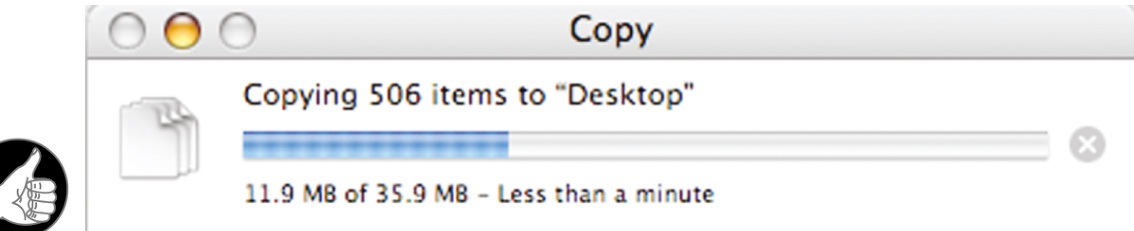

Even small amounts of data can be made easier to scan if they are structured. Two examples are telephone and credit card numbers (see Fig. 3.9). Such numbers should be broken into parts—often called “chunks”—to make them easier to scan and remember. The right size for chunks was determined by psychologists and humanfactors researchers decades ago when telephone numbers and credit card numbers were introduced (e.g., Miller, 1956). It is based on the capacity of human short-term memory (Moran, 2016) (see also Chapter 7).

即使是少量的数据,如果它们结构化,也会更容易扫描。电话号码和信用卡号码就是两个例子(见图 3.9)。这些数字应该被分成几部分——通常称为“块”——以便更容易扫描和记忆。块的大小是由心理学家和人类因素研究人员在几十年前电话号码和信用卡号码被引入时确定的(例如,米勒,1956 年)。这是基于人类短期记忆的容量(莫兰,2016 年)(另见第 7 章)。

图 3.9 当电话号码和信用卡号码被分成“块”时,它们更容易扫描、理解和记忆。

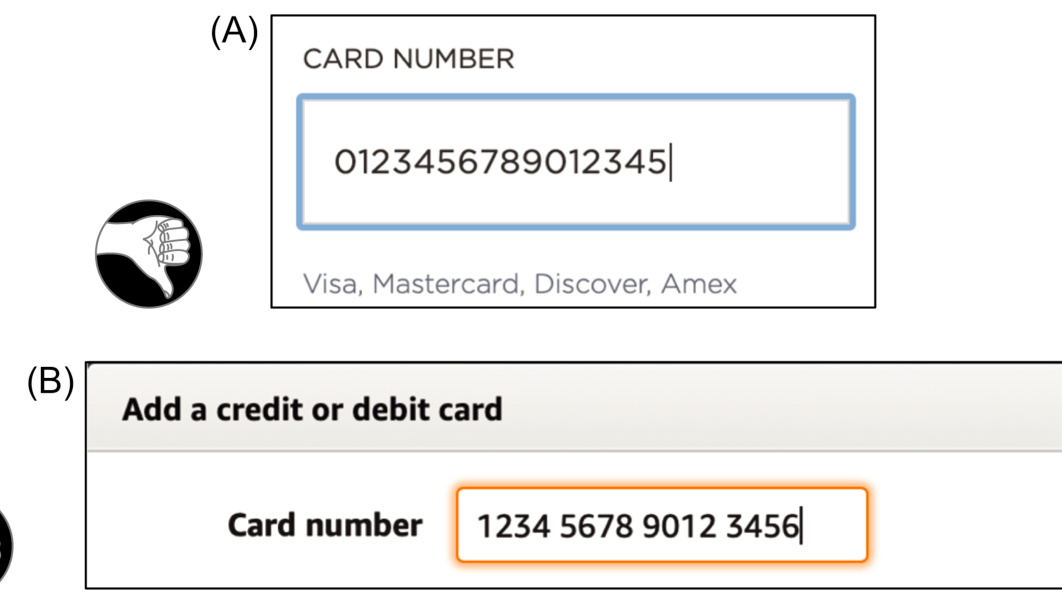

图 3.10 (A) 在 KP.org(2020 年),信用卡号码不能包含空格或其他标点符号,这使得它们难以扫描和验证。(B) 在 Amazon.com(2020 年),当用户输入号码时,会自动添加空格。

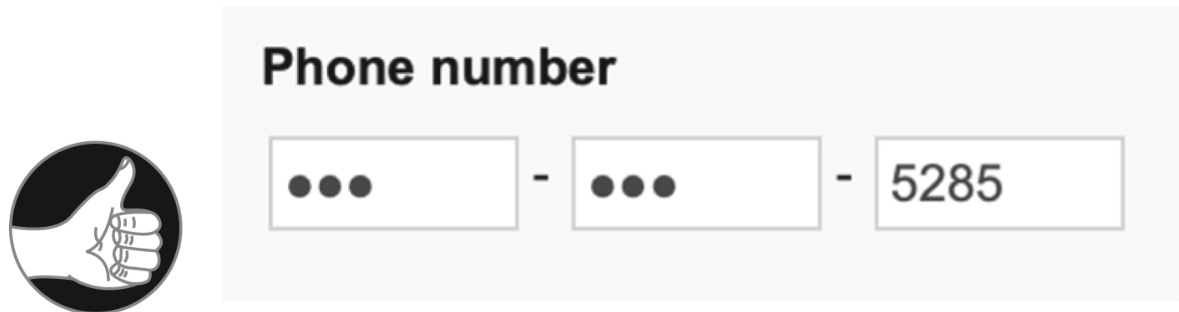

图 3.11 BankOfAmerica.com(2020 年)将电话号码分成三部分,这使得输入格式错误的号码变得不可能。

不幸的是,当今许多数字演示中的电话号码和信用卡号码既不进行分段,也不允许用户插入空格、连字符、括号或其他标点符号(见图 3.10A)。这使得人们更难扫描一个号码或验证他们是否输入正确,因此被认为是一个用户界面设计错误(约翰逊,2007 年)。

为了更加用户友好,用户界面应该支持数字的分段,允许用户使用空格或其他标点符号将它们分开(见图 3.10B)。

或者,设计师可以通过为号码的每个部分提供单独的字段来支持长数字的分段。即使要输入的数据严格来说不是数字,单独的数据字段也可以提供有用的视觉结构。日期和电话号码就是一个例子,其中分段字段可以提高可读性并帮助防止数据输入错误(见图 3.11)。

“分段”数据不仅有助于人们扫描、理解和记忆长数字,还有助于记忆和理解其他类型的数据。它使数据更好地适应人类记忆和注意力的局限性,这些内容将在第 7 章和第 8 章中更详细地讨论。

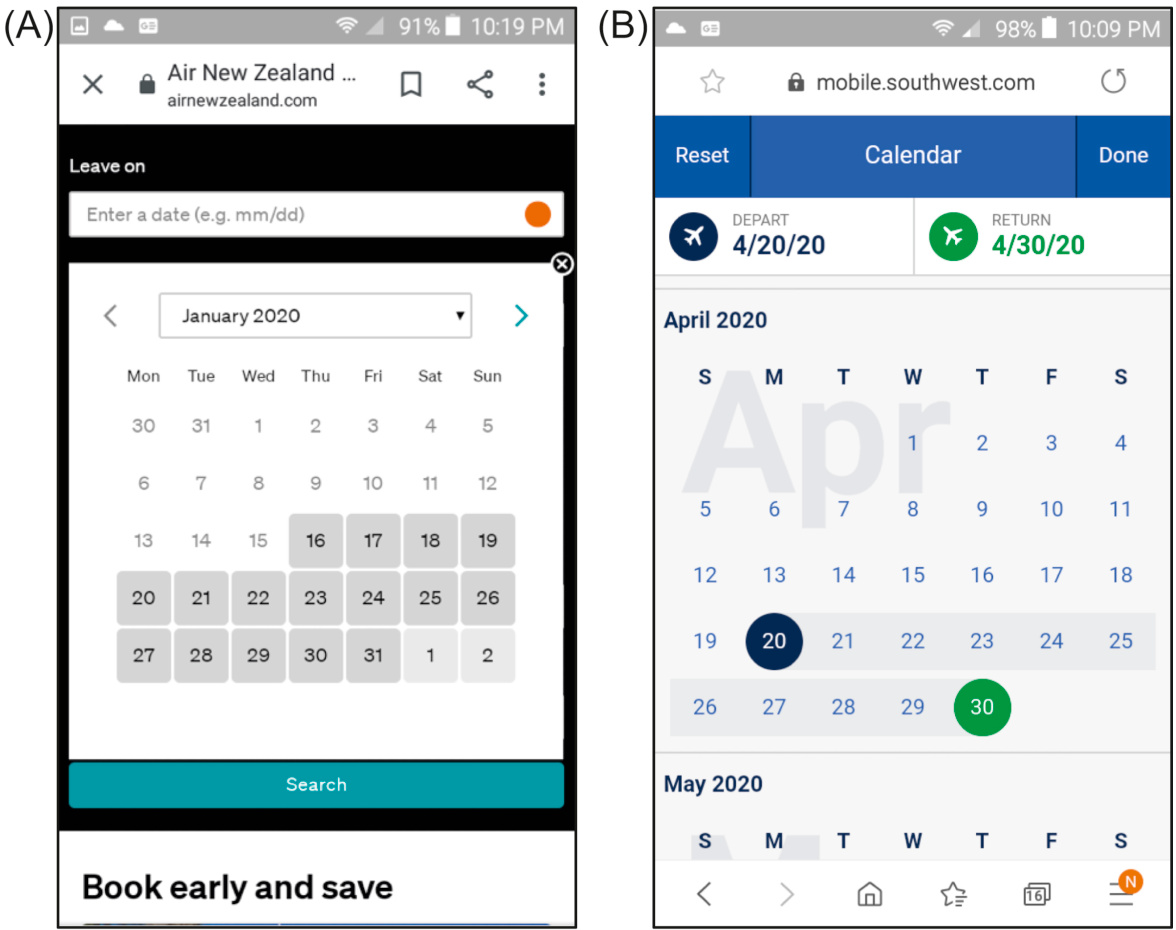

为输入提供更多结构:数据特定控制

从分段文本字段的结构升级到数据特定控件。设计师可以将文本字段和其他控件组合起来创建混合控件,以获取特定类型的数据。使用数据特定控件,用户无法输入无效数据,因此消除了一种可能的用户错误类型。

例如,如今大多数航空公司使用文本字段和日历控件让客户选择航班日期(见图 3.12)。

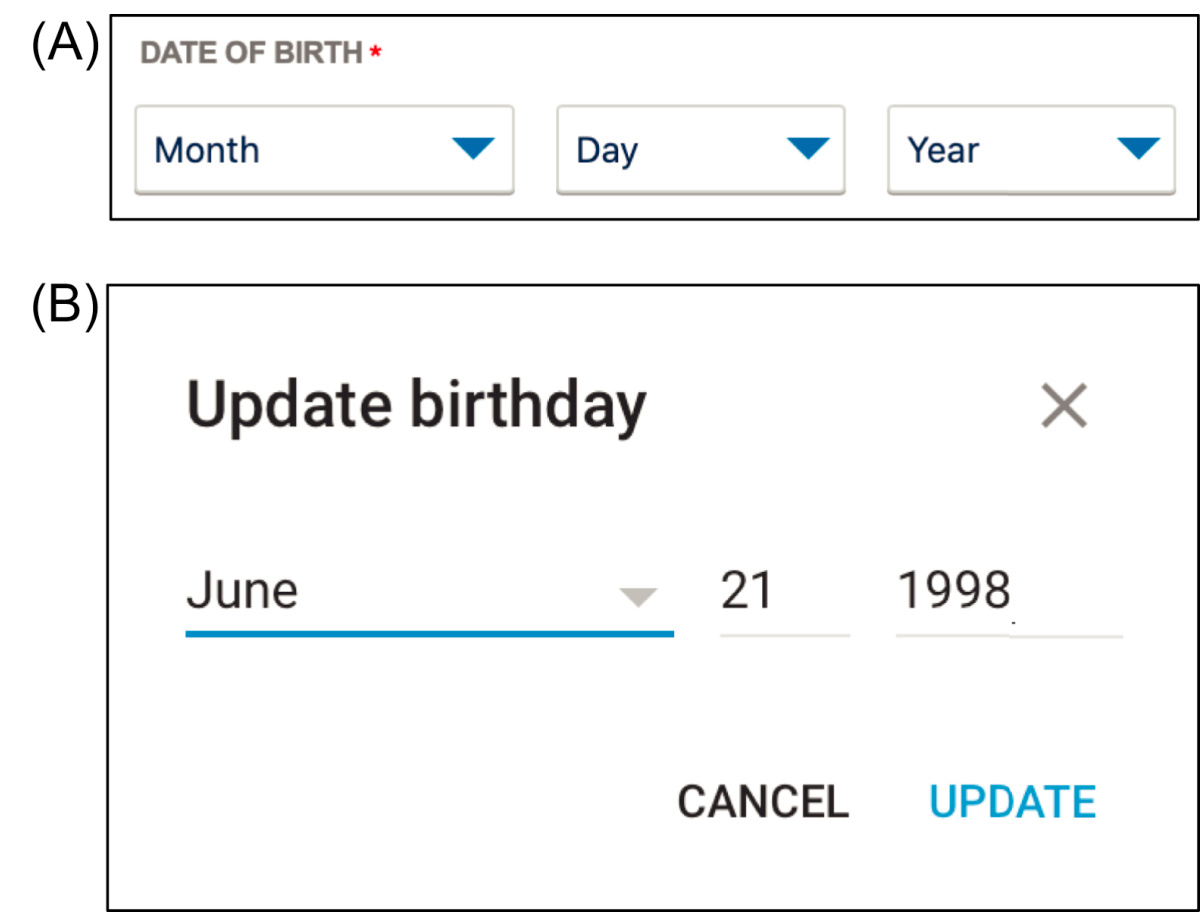

结构化的数据特定控件也可以由菜单构建。例如,Southwest.com 使用月份、日期和年份菜单来构建出生日期控件(见图 3.13A)。菜单也可以与文本字段组合,就像 Google 的出生日期控件(见图 3.13B)一样。

图 3.12 获取航班日期,大多数航空公司使用混合控件:文本字段

图 3.13 出生日期控制:(A) 2020 年西南航空公司菜单;(B) 2020 年谷歌菜单+文本字段。

重要要点

• 以简洁、结构化的方式呈现信息,使人们更容易浏览、理解和记忆。消除不必要的词语和重复。使用项目符号和编号列表,而不是文本段落。

• 视觉层次结构——将内容分成清晰标记的部分和子部分——是结构化信息的“最佳实践”方法。

• 使用屏幕阅读器可以识别为标题的部分标题和标签来分层信息,有助于视障人士找到他们想要的内容。

• 数据分块——如电话号码、信用卡号码、序列号——有助于人们浏览、输入和记忆。

第四章 :我们的色彩视觉有限

Chapter 4: Our Color Vision is Limited

摘要

这一章从视觉系统神经生理学概述开始,将其与数码相机的工作原理进行比较。然后解释了人类色觉的优缺点:我们可以检测对比度和边缘,但不能检测整体亮度水平;颜色的辨别很大程度上取决于其显示方式和显示类型;人们的颜色辨别能力各不相同。本章解释了色盲是什么,以及它并不意味着无法看到颜色。本章最后提供了设计指南。

关键词

亮度;色盲;色觉错觉;色觉;视锥细胞;对比度;显著颜色;边缘检测;指南;冗余;视网膜;视杆细胞;优点;缺点

色觉是有限的

人类的色彩感知既有优势也有限制,其中不少与用户界面设计相关,例如:

我们的视觉是为检测反差(边缘)优化的,而不是绝对亮度;

我们辨别颜色的能力依赖于颜色的呈现方式;

有些人是色盲;

屏幕和观看条件会影响用户对颜色的感知。

要理解人类色觉的这些特点,我们首先简单描述一下人类视觉系统如何处理环境中的颜色信息。

要理解人类色觉的这些特点,我们首先简单描述一下人类视觉系统如何处理环境中的颜色信息。

色觉是如何工作的

如果你在学校上过心理学或者神经生理学的课程,或许你已经知道了眼睛内的视网膜(也就是眼球里聚焦成像的表面)有两类感光细胞:视杆细胞和视锥细胞。你或许也了解了视杆细胞察觉光线强度但感觉不到颜色,而视锥细胞能察觉颜色。最后,你或许还知道有三类视锥细胞,分别对红色、绿色和蓝色光敏感,这意味着我们的色觉与摄影机和计算机显示器类似,通过红色、绿色和蓝色像素的组合来探测或形成多种颜色。

人们在学校里学到的知识只有一部分是正确的。对于视觉系统正常的人,视网膜上的确有对亮度敏感的视杆细胞和三种对不同频率的光敏感的视锥细胞。然而目前,大部分人在学校里学到的知识与真实的情况存在有一定差距。

首先,处于工业化社会中的我们几乎用不到视杆细胞,它们只在低亮度下工作。在光线很暗的环境中,如 19 世纪前我们祖先所生活的环境中,它们才起作用。今天,我们只有在烛光晚餐、夜里在黑暗屋子周围摸索、夜晚在外宿营等情况下才用到视杆细胞。(见第 5 章。)在明亮的白天和人工照明环境(我们在此打发的时间最多)下,视杆细胞则完全过曝了,不能提供任何有用信息。大部分时间里,我们的视觉完全基于视锥细胞所提供的信息(Ware,2008)。

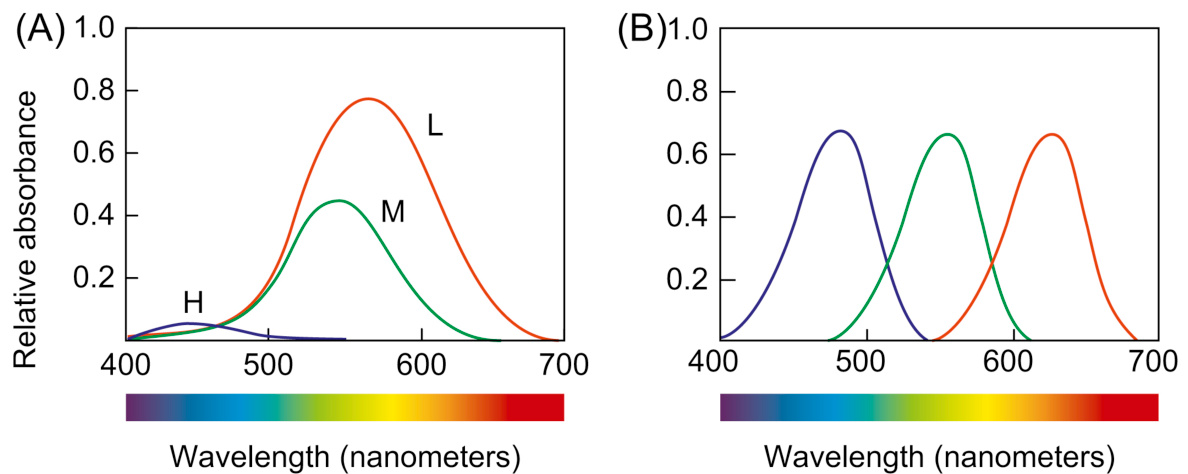

那么视锥细胞是如何工作的?三种视锥细胞分别对红色、绿色和蓝色光敏感吗?事实上,每种视锥细胞敏感的光谱比你想象的还要广,而且三者的敏感范围是互相重叠的。此外,这三类视锥细胞的敏感度相差非常大(见图 4.1A):

图 4.1 视网膜三类视锥细胞对光的敏感度(A)对比人造红色、绿色和蓝色光感受器对光的敏感度(B)。

- 低频。这些视锥细胞对整个可见光频谱都敏感,但对处于频谱中间的黄色和低频的红色最敏感。

- 中频。这些视锥细胞对从高频的蓝色到中频偏低的黄色和橙色有反应,但在整体上,它们的敏感度低于低频的视锥细胞。

- 高频。这些视锥细胞对可见光的高频部分(紫色和蓝色)最敏感,但对中频(如绿色)的敏感度较低。此类视锥细胞的整体敏感度较前两者都低,数量上也更少。因此,我们的眼睛对蓝色和紫色不如对其他颜色敏感。

比较我们视网膜锥状细胞的光敏感性图(图 4.1A)与如果电气工程师设计我们的视网膜为像相机一样的红、绿、蓝敏感的受体镶嵌图(图 4.1B)可能的样子。

在了解了我们视网膜上的这三类视锥细胞敏感度的奇怪关系后,我们就会对大脑如何综合视锥细胞传来的信号从而看到各种颜色而感到好奇了。

答案就是:做减法。大脑后部视皮层上的神经元将通过视神经传递来的中频和低频视锥细胞的信号去掉,得到一个“红一绿”减影信号通道。另一些神经元将来自高频和低频视锥细胞的信号去掉,得到一个“黄一蓝”减影信号通道。第三组神经元将来自低频和中频视锥细胞的信号相加产生一个整体的亮度(或者叫“黑一白”)信号通道。这三个通道叫做颜色对抗通道。

接下来,大脑对所有颜色对抗通道做更多的减法处理:来自视网膜上某个区域的信号将被来自其附近区域的类似信号减掉。

视觉是为边缘反差而不是为亮度优化的

Vision is Optimized for Detection of Edges, Not Brightness

所有这些减法处理使得我们的视觉系统对颜色和亮度的差别,即对比鲜明的边缘,比对绝对的亮度水平要敏感得多。

为验证这一点,请看图 4-2 中内部的色块。内部色块右边的颜色看上去更深一些,但实际上左右两边的灰度是一样的。我们的视觉系统对差异十分敏感,因为外部矩形块的左边颜色较深,右边颜色较浅,这才使得我们感觉,内部色块的左边较浅,右边较深。

图 4.2 内部色块右边的颜色看上去更深一些,但实际上左右两边的灰度是一样的

视觉系统对对比度敏感而不是对绝对亮度敏感是人类的一个优势,这样我们原始社会的祖先无论是在阳光普照的响午,还是在阴云密布的清晨,都能分辨出躲在附近灌木丛中的豹以及其他类似的危险动物。同样,对颜色对比度而不是对绝对色彩敏感,会让我们觉得阳光下和阴影里的玫瑰花都一样红。

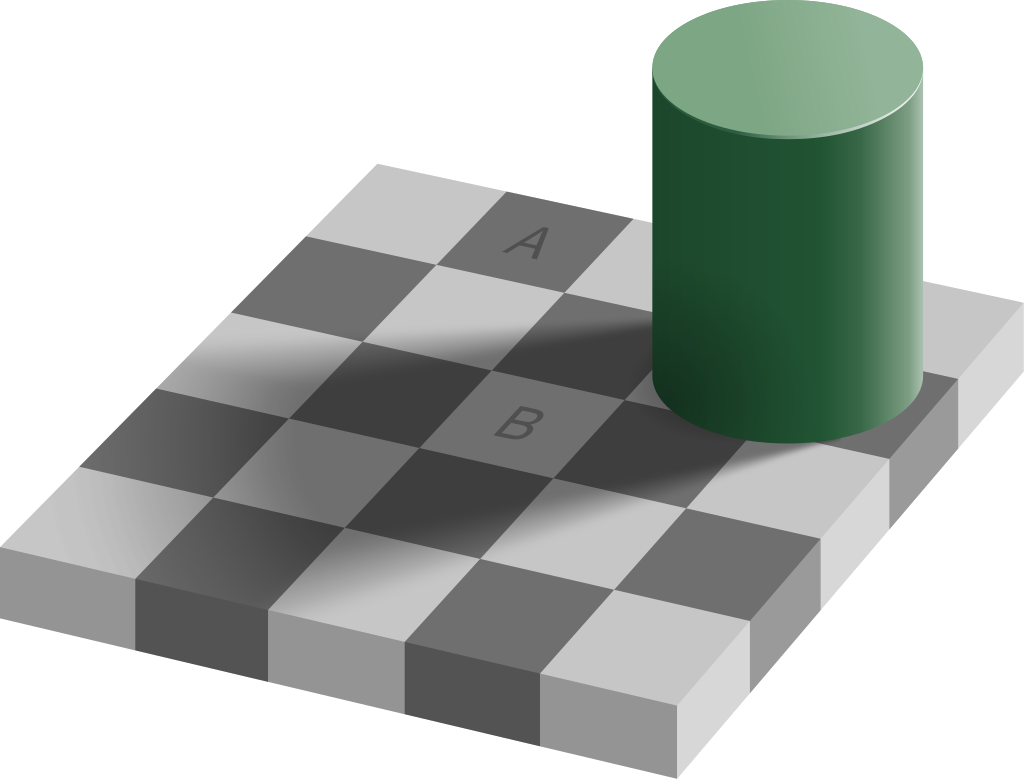

马萨诸塞理工学院的脑研究者爱德华·H·阿德森开发了一个出色的图示,说明了我们的视觉系统对绝对亮度的不敏感性和对对比度的敏感性(见图 4.3)。尽管可能难以置信,棋盘上的方块 A 与方块 B 的色调完全相同。方块 B 看起来是白色,是因为它被描绘在圆柱体的阴影中。

图 4.3 标记的方块 A 和方块 B 是同一种灰色,但我们觉得 B 是白色的,因为它在“影子”里

区别颜色的能力取决于颜色是如何呈现的

我们对颜色之间差别的察觉也是有限的。基于视觉系统运作的方式,有以下三个呈现因素影响了我们区分颜色的能力:

- 深浅度两个颜色越浅(不饱和),就越难将它们区分开(见图 4.4A)。

- 色块的大小对象越小或者越细,就越难辨别它们的颜色(见图 4.4B)。

- 分隔的距离两个色块之间离得越远,就越难区分它们的颜色,尤其是当它们之间的距离大到眼球需要运动时(见图 4.4C)。

图 4.4 影响区分颜色能力的因素:(A) 肤色、(B) 大小和 (C) 分离。

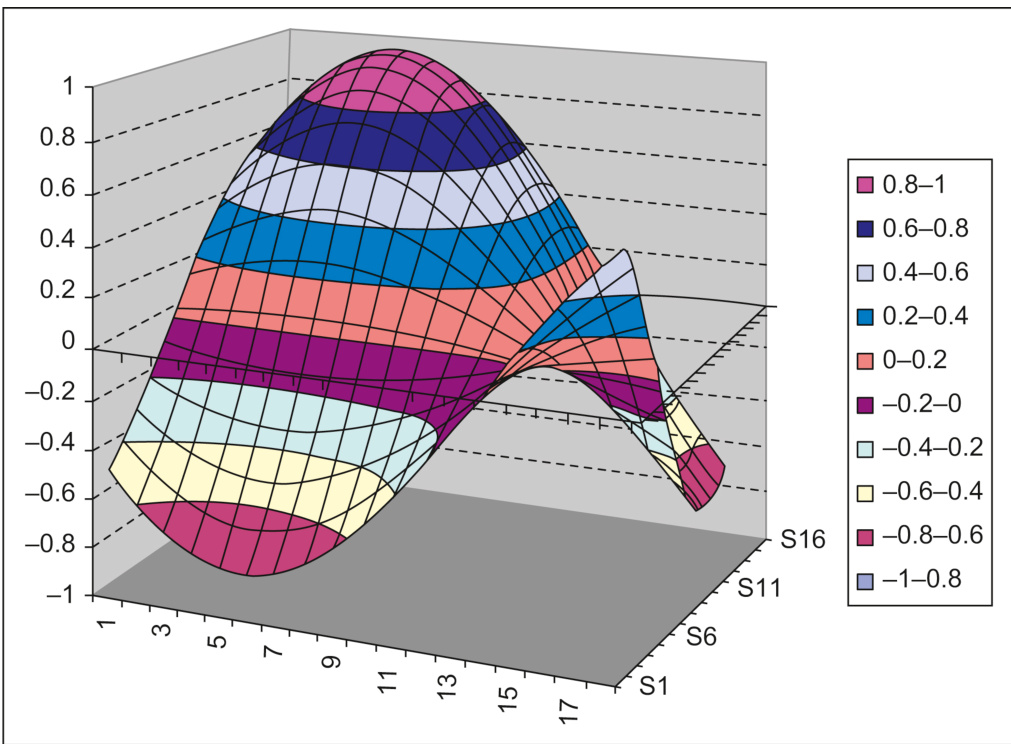

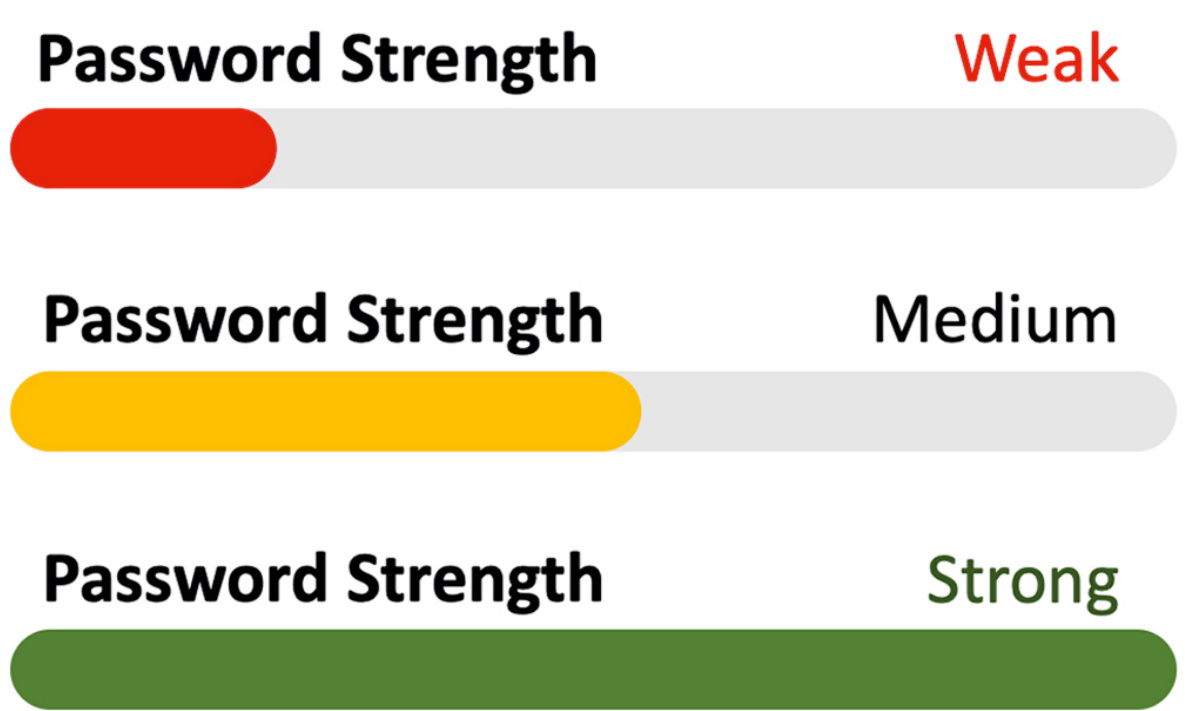

图 4.5 展示了一个颜色过浅以至于任何设备上的任何人都不容易看到的例子。这是一个模拟的航空公司网站登机步骤指示器。当前步骤在圆圈内仅用浅绿色标记。也许你能区分绿色填充的圆圈和白色圆圈,但如果你有视力障碍或你在灰度屏幕或白平衡问题的数字投影仪上查看,也许你无法区分。

图 4.5 当前步骤仅用浅色标记,这使得一些用户难以看清。

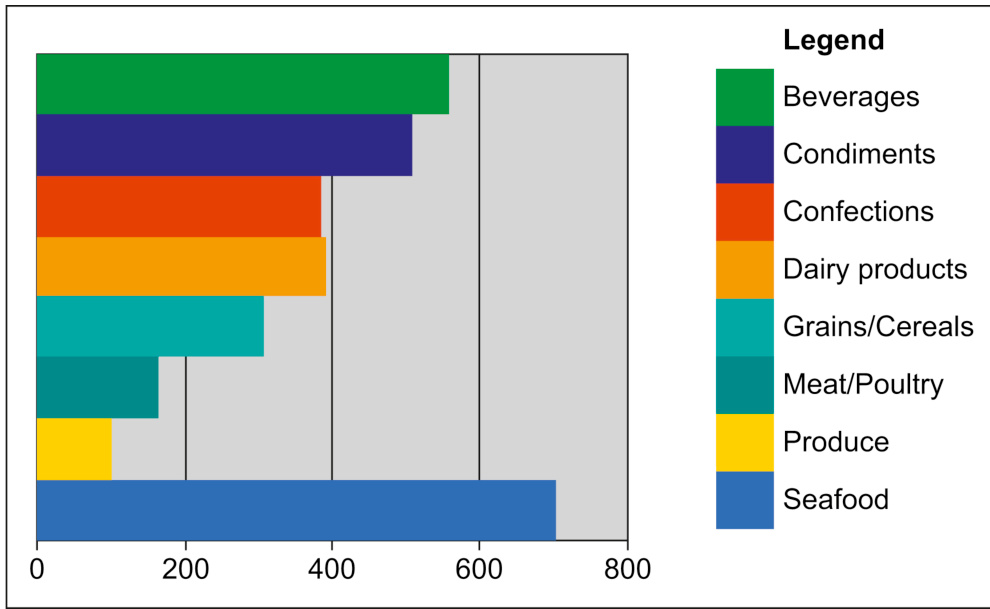

在数据图表中经常能看到小的色块。许多商业制图软件会在图表旁边生成图例,但图例中的色块非常小(见图 4.6)。图例中的色块应该大到能帮助用户辨别不同的颜色(见图 4.7)。

图 4.6 图例中的小色块很难区分。

图 4.7 大色块更容易区分颜色。

网站上常常用颜色来区别访问过和未访问过的链接。在某些网站上,二者的颜色太接近了。明尼阿波利斯市的联邦储备银行的网站(见图 4.8)就有这样的问题。此外,它用的两种颜色是深浅不同的蓝色,而蓝色是人眼最不敏感的颜色。你能找到那两个访问过的链接吗

图 4.8 在MinneapolisFed.org 上,已访问和未访问链接之间的颜色差异过于微弱。

色盲

交互式系统设计原则中影响颜色呈现的第四个因素是颜色是否可以被有常见类型色盲的人区分。除了严重情况外,有色盲并不意味着完全无法看到颜色。这意味着一个视力正常的人的三种类型的色觉锥状细胞受体细胞(见上文“颜色视觉如何工作”部分)并不全部功能,导致难以或不可能区分某些颜色对。大约

图 4.9 红绿色盲的人无法区分(A)深红色和黑色,(B)蓝色和紫色,(C)浅绿色和白色。

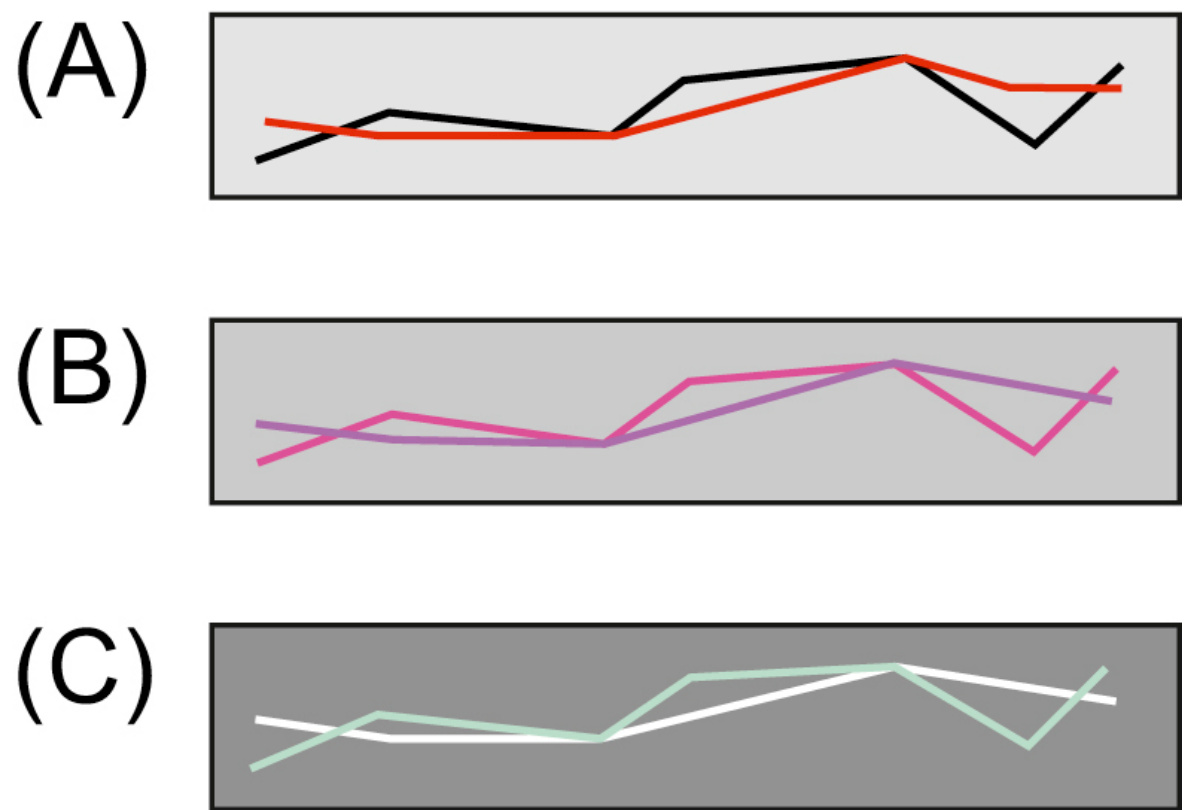

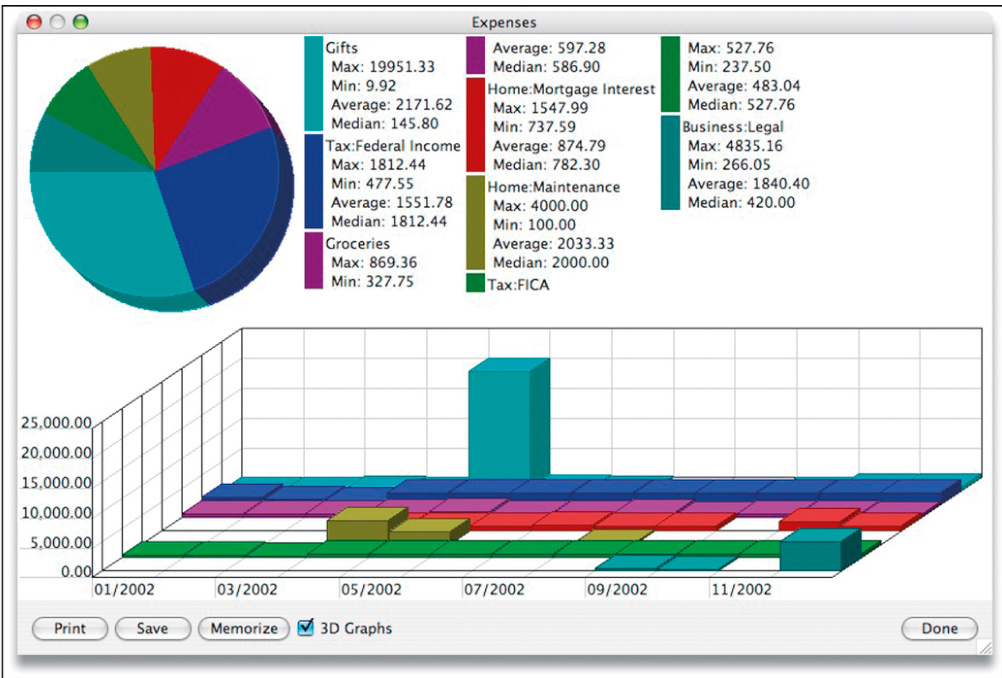

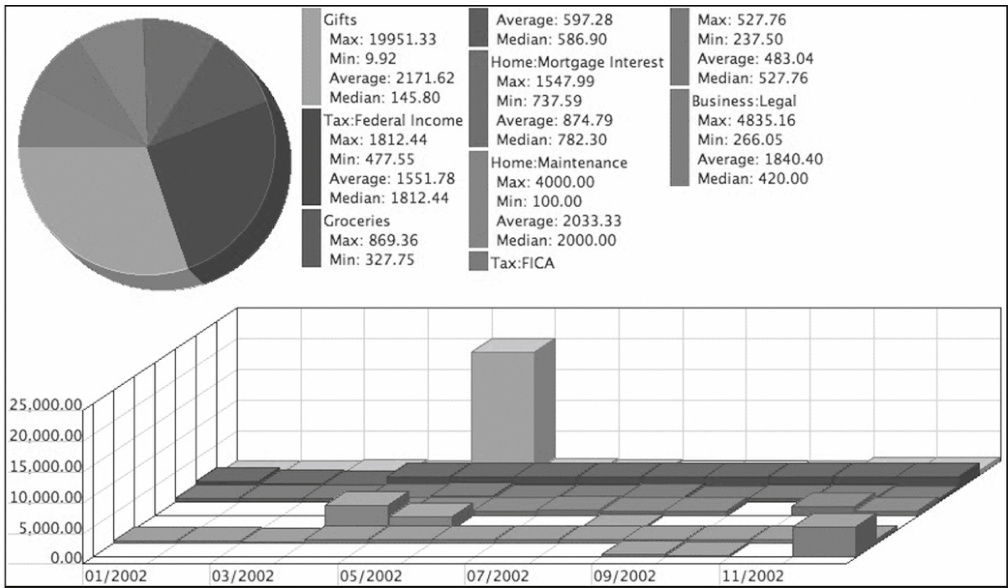

家庭金融软件 MoneyDance 提供了家庭支出分解的图表,用不同颜色来标记不同类别的消费(见图 4.10)。不幸的是,其中许多颜色是色盲人士无法区分的色相。例如红绿色盲的人无法区分蓝色和紫色,或者绿色和卡其色。如果你不是色盲,可以将图像转换为灰度图,来了解图上哪些颜色是难以区分的(见图 4.11)但最好像本章节后续内容“使用色彩的准则”中将要提到的那样,用色盲滤镜或模拟器来测试一下图像(见图 4.12)。

图 4.10 Moneydance 的图表使用了某些用户无法区分的颜色。

图 4.11 转换为灰度图后的 MoneyDance 图表

图 4.12 Google 的标志:(A)正常视觉下的观察效果,(B)红绿色盲滤镜下的观察效果

影响我们区分颜色的外部因素

External Factors That Influence Our Ability to Distinguish Colors

外部环境因素也能影响人们分辨色彩的能力,例如以下一些因素:

• 颜色显示的变化。电脑显示屏因各自采用的技术、驱动程序或者色彩设置的不同,在色彩显示上存在差异。即使是采用同样设置的同一型号显示器,在色彩显示上也会有轻微的不同。在一台显示器上看起来是黄色的东西,在另一台上看起来可能就是米黄色。而在一台显示器上看起来明显不同的颜色,在另一台上看起来也许就是相同的。

• 灰度显示。虽然大部分显示器是彩色的,但还是有些设备,尤其是小型手持设备,采用了灰度显示器。图 4.13 展示了在灰度显示器上,一些原本颜色不同的区域看起来是相同的。

• 日间/夜间调整和暗黑模式。大多数现代智能手机、平板电脑和电脑都可以调整它们的色彩平衡,无论是按需调整还是根据一天中的时间进行调整。一些色彩调整是微妙的,例如当设备减少显示器中的蓝色含量,以避免在晚上使用设备后干扰用户的睡眠能力时。 其他颜色调整非常明显,例如切换到“暗黑模式”,它会在深色背景上显示浅色内容(讽刺的是,这就像几十年前大多数电脑终端的样子)。所有这些都会影响用户在用户界面中看到的颜色。

图 4.13 电子书阅读器带灰度屏幕。

显示器角度

一些电脑显示器,尤其是液晶显示器,在直视角度观看要比偏一定角度看时效果好得多。当从一定角度观看液晶屏时,色彩以及色彩之间差别都会发生变化。

环境光线

照射在屏幕上的强光会在将明暗区域的差别“冲洗”掉之前先将色彩“冲洗”掉,将彩色屏变成灰度屏,在阳光直射下使用过银行自动柜员机的人都体会过这种情况。办公室里的眩光和百叶窗的影子都能使颜色看起来不一样。

这些外部因素通常不在软件设计者的控制范围内。因此,设计者们应记住他们并不对用户的观看体验具有完全的控制。在普通办公室照明条件下,用开发环境里的电脑显示器看到的高辨识度的色彩,在软件的其他使用环境里就未必能够分辨得出来。

使用色彩的准则

在依赖颜色来传递信息的交互软件系统中,遵循以下 5 条准则,以保证用户能够获取信息。

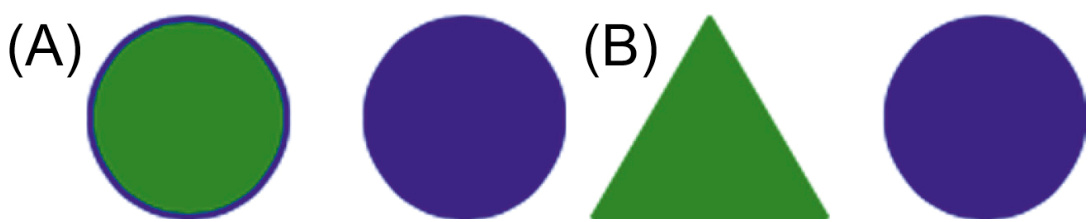

使用鲜明的颜色。回忆一下,我们的视觉系统结合视网膜视锥细胞的信号,产生三个颜色对立通道:红-绿、黄-蓝和黑-白(亮度)。人们最容易区分的颜色是那些在一个颜色感知通道上产生强烈信号(正向或负向),而在其他两个通道上产生中性信号的颜色。毫不奇怪,这些颜色是红、绿、黄、蓝、黑和白(见图 4.14)。所有其他颜色都在多个颜色通道上产生信号,因此我们的视觉系统无法像区分这六种颜色那样快速轻松地将其与其他颜色区分开来(Ware,2008)。

分离强烈的对立颜色。将对立颜色紧挨着或放在彼此上面会导致令人不适的闪烁感,因此应避免(见图 4.15)。

通过饱和度、亮度和色调来区分颜色。为了使您的软件使用的颜色对所有有视力的用户都可见,请避免使用微妙的颜色差异。确保颜色之间的对比度足够高(但请参阅指南 5)。一种测试颜色是否足够不同的方法是将其转换为灰度。如果您在灰度渲染时无法区分颜色,则它们的差异不够。

避免使用色盲人士无法区分的颜色组合。此类组合包括深红色与黑色、深红色与深绿色、蓝色与紫色、浅绿色与白色。不要将深红色、蓝色或紫色与任何深色搭配使用。相反,应将深红色、蓝色和紫色与浅黄色和绿色搭配使用。使用在线色盲模拟器 4 检查网页和图像,以查看各种色觉缺陷的人将如何看到它们。

图 4.14 最独特的颜色:黑、白、红、绿、黄和蓝。每种颜色只在一种颜色对立通道上产生强信号。

图 4.15 对抗色直接放在一起,让人崩溃

FIGURE 4.16 Don’t use color alone to convey meaning (A). Use it redundantly with other cues—e.g., shape (B).

不要仅用颜色来传达含义(A)。将其与其他线索一起重复使用——例如,形状(B)。

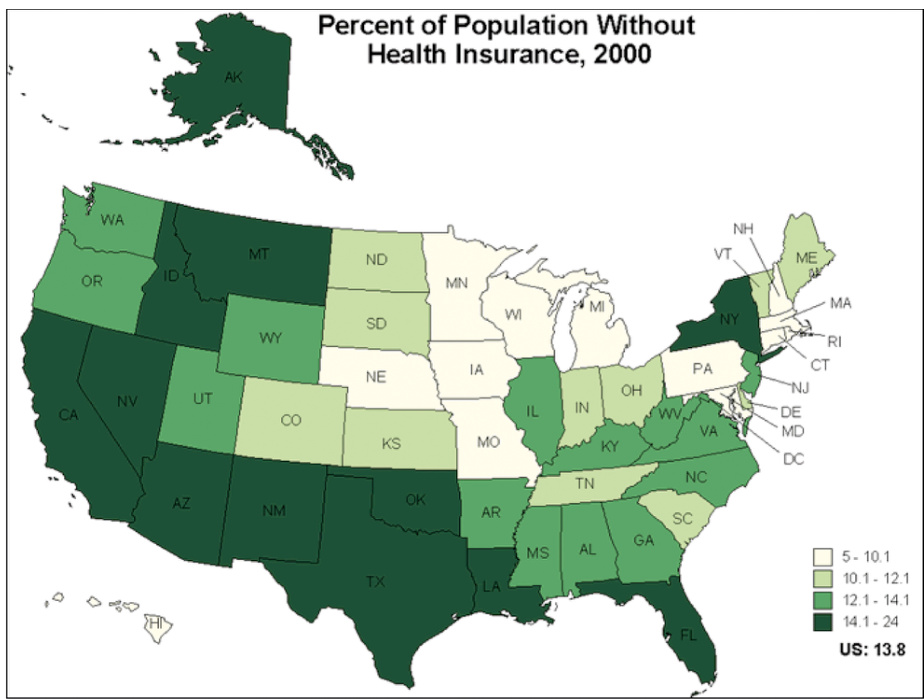

MinneapolisFed.org 的图表使用了所有视力正常的人在任何显示器上都可见的阴影差异。

将颜色与其他线索一起重复使用。不要仅依赖颜色。如果你用颜色来标记某物,也要用其他方式来标记它。例如,如果绿色表示一种含义,蓝色表示另一种含义,不要显示绿色和蓝色的点;显示一个绿色的三角形与一个蓝色的点,这样形状和颜色都能表示差异(见图 4.16)。

FIGURE 4.18 (A)设计不佳;(B)改进的、更易访问的设计:当前步骤使用加粗和更饱和的颜色重复突出显示。

美联储银行的图表遵循上述第 3 条指南,使用了绿色阴影(见图 4.17)。这是一个设计良好的图表。任何视力正常的人都能读懂它。

现在我们使用上述第 5 条指南来修复之前讨论的设计问题(见图 4.5),其中模拟航空公司登机过程中的当前步骤仅用浅绿色标记(见图 4.18A)。一种简单的纠正方法是,用粗圈标记当前步骤,用粗体步骤编号,在圆圈下方用粗体标签,并增加绿色的饱和度,使其与白色背景形成更强对比(见图 4.18B)。为了使使用屏幕阅读器的视障人士知道他们当前的步骤,还可以将当前步骤的 ALT 文本设置为“当前步骤”来标记它。通过这些改进,当前步骤被冗余地标记,正如第 4 条指南所推荐的。

重要要点

• 拥有正常色觉的人的视网膜中有三种类型的视锥细胞。色盲者只有两种功能类型的视锥细胞——在罕见情况下有一种类型——而一小部分女性有四种类型。

• 人类色觉主要通过减法工作:红减绿和蓝减黄。这使得我们的视觉系统主要对对比度、边缘和快速变化敏感,而对整体亮度水平或绝对颜色相对不敏感。

• 我们区分两块颜色区域的能力取决于:

• 肤色:两块颜色区域越浅,区分它们就越困难。

• 大小:区域越大,我们区分颜色就越容易。分离:它们越近,越容易区分。

• 有一些外部因素会影响我们区分颜色的能力:

• 颜色显示可能会在色彩平衡上有所不同。

• 一些显示器,例如许多电子阅读器上的显示器,是灰度或黑白。

• 许多现代显示器允许用户调整色彩平衡。夜间模式(降低蓝色水平)和暗色模式与亮色模式。

• 观看某些屏幕的角度会影响颜色的呈现。

• 环境光。

• 使用颜色的指南:

• 使用独特的颜色。

• 分离强烈的对手颜色。

• 根据饱和度、亮度和色调来区分颜色。

• 避免色盲人士无法区分的颜色组合。

• 使用颜色与其他线索重复。

1色盲人士可能只有两种或三种视锥细胞类型,而一些女性有四种(Eagleman,2012 年;Macdonald,2016 年)。

2总亮度总和忽略了高频(蓝紫色)视锥细胞的信号。这些视锥细胞非常不敏感,它们对总量的贡献可以忽略不计,因此忽略它们差别不大。

3已经查看了图 4.8 中的链接:已批准的住房单元和房价指数。

4在网络上搜索“色盲过滤器”或“色盲模拟器”。

第五章:我们的边界视觉很糟糕

摘要

人类的视觉在视觉场中央的一个小区域称为中央凹处具有高分辨率,而在其他地方分辨率较低。本章解释了造成这种现象的神经生理因素,例如中央凹和周边区域的视锥细胞密度差异很大。然后讨论了周边视觉的重要功能,例如引导中央凹和夜视。本章的大部分内容讨论了设计视觉用户界面时的重要意义和指南。例如,在人的视觉场周边以柔和颜色呈现的静止物品通常不会被注意到,因此错误消息应以强烈的对比色或短暂振动来吸引注意力。

关键词

注意力;视锥细胞;错误消息;中央凹;运动检测;夜视;周边视觉;分辨率;视网膜;视杆细胞;扫视;视觉皮层;视觉“弹出”;视觉搜索

第四章解释了人类视觉系统与数码相机在检测和处理颜色方面的不同。我们的视觉系统与相机在分辨率上也有差异。在数码相机的感光元件上,感光单元均匀地分布在一个紧密的矩阵中,因此整个图像帧的空间分辨率是恒定的。人类的视觉系统则不是这样的。

本章解释了原因:

• 在人眼视野的周边呈现的、颜色暗淡的静止物体通常不会被注意到。• 周边区域的运动通常会被注意到。

Resolution of the Fovea Compared With the Periphery

视网膜中央凹与周边的分辨率比较

The spatial resolution of the human visual field drops greatly from the center to the edges for three reasons:

人类视野的空间分辨率从中心到边缘会显著下降,原因有三点:

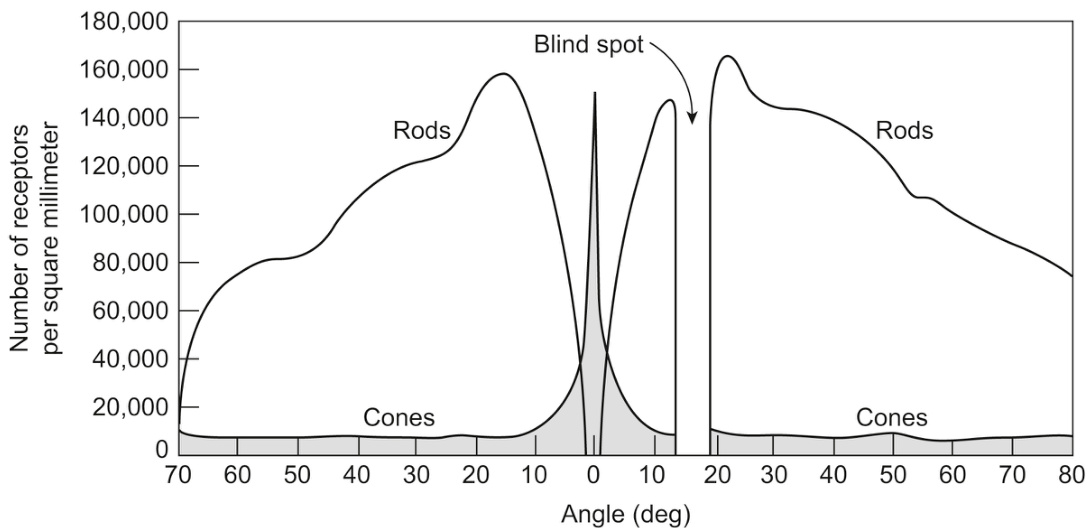

• Pixel density . Each eye has six to seven million retinal cone cells. They are packed much more tightly in the center of our visual field—a small region called the fovea—than at the edges of the retina (see Fig. 5.1). The fovea has about 158,000 cone cells in each square millimeter. The rest of the retina has only 9000 cone cells per square millimeter. • Data compression . Cone cells in the fovea connect 1:1 to the ganglial neuron cells that begin the processing and transmission of visual data, while elsewhere on the retina, multiple photoreceptor cells (cones and rods) connect to each ganglion cell. In technical terms, information from the visual periphery is compressed (with data loss) before transmission to the brain, while information from the fovea is not compressed.

• 像素密度。每只眼睛有六到七百万个视网膜视锥细胞。它们在视觉中心的中央区域——一个称为黄斑的小区域——比在视网膜边缘更紧密地排列(见图 5.1)。黄斑每个平方毫米约有 158,000 个视锥细胞。视网膜的其余部分每个平方毫米只有 9,000 个视锥细胞。• 数据压缩。黄斑中的视锥细胞与开始处理和传输视觉数据的神经节细胞一对一连接,而在视网膜的其他地方,多个感光细胞(视锥细胞和视杆细胞)连接到每个神经节细胞。从技术术语上讲,来自视觉外周的信息在传输到大脑之前会被压缩(并丢失数据),而来自黄斑的信息不会被压缩。

FIGURE 5.1Distribution of photoreceptor cells (cones and rods) across the retina. From Lindsay, P., Norman, D.A., 1972. Human Information Processing. Academic Press, New York and London.

图 5.1 视网膜上感光细胞(视锥细胞和视杆细胞)的分布。引自 Lindsay, P., Norman, D.A., 1972. 人类信息处理。学术出版社,纽约和伦敦。

• Processing resources . The fovea is only about

• 处理资源。中央凹仅占视网膜的

The result is that our vision has much, much greater resolution in the center of our visual field than elsewhere (Lindsay and Norman, 1972). Stated in developer jargon: in the center

结果是,我们的视野中心比其他地方具有更高的分辨率(Lindsay and Norman, 1972)。用开发者术语来说:在视野中心

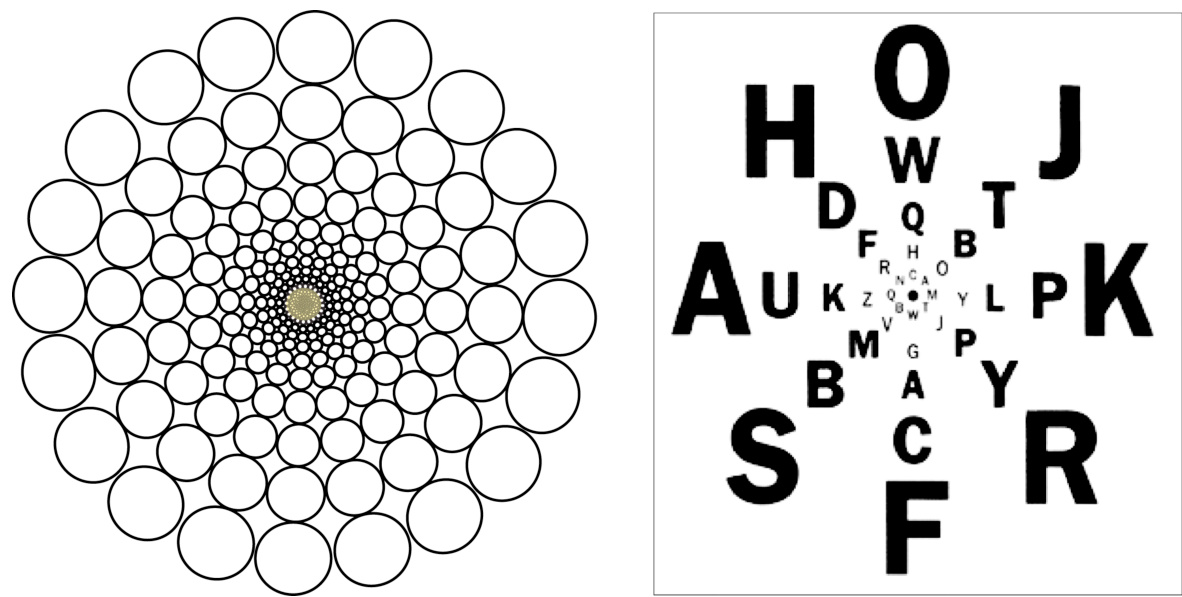

To visualize how small the fovea is compared with your entire visual field, hold your arm straight out and look at your thumb. Your thumbnail, viewed at arm’s length, corresponds approximately to the fovea (Ware, 2008). While you have your eyes focused on the thumbnail, everything else in your visual field falls outside your fovea.

为了直观地感受中央凹与整个视野相比有多么小,将手臂伸直并注视你的拇指。在手臂的长度上看你的指甲盖,大约相当于中央凹(Ware, 2008)。当你专注于指甲盖时,视野中的其他一切都在你的中央凹之外。

In the fovea, people with normal vision have very high resolution: they can resolve several thousand dots within that region—better resolution than many of today’s pocket digital cameras. Just outside the fovea, the resolution is already down to a few dozen dots per inch viewed at arm’s length. At the edges of our vision, the “pixels” of our visual system are as large as a melon (or human head) at arm’s length (see Fig. 5.2).

在中央凹处,具有正常视力的人具有非常高的分辨率:他们可以在该区域内分辨出数千个点——其分辨率优于当今许多口袋式数码相机。在中央凹处的外围,分辨率已经下降到每英寸几十个点,在手臂长度处观察。在我们视野的边缘,我们视觉系统的“像素”在手臂长度处有 melon(或人头)那么大(见图 5.2)。

Even though our eyes have more rods than cones—125 million versus 6 to 7 million—peripheral vision has much lower resolution than foveal vision. This is because while most of our cone cells are densely packed in the fovea (in

尽管我们的眼睛比视锥细胞多出更多的视杆细胞——1250 万对 6 到 700 万——但周边视力比中央凹视力分辨率低得多。这是因为虽然我们大多数的视锥细胞在中央凹处密集分布(在视网膜的

FIGURE 5.2 The resolution of our visual field is high in the center but much lower at the edges. Right image from Vision Research, vol. 14, 1974. Elsevier.

图 5.2 我们的视野在中心分辨率很高,但在边缘则低得多。右图来自《视觉研究》第 14 卷,1974 年。Elsevier。

The resolution in your peripheral vision is roughly equivalent to looking through a frosted shower door, and yet you enjoy the illusion of seeing the periphery clearly.… Wherever you cast your eyes appears to be in sharp focus, and therefore you assume the whole visual world is in focus.

你的周边视觉分辨率大致相当于透过磨砂淋浴门看东西,但你仍然享受看到周边清晰的错觉……无论你把目光投向哪里,似乎都是清晰的焦点,因此你假设整个视觉世界都是清晰的。

If our peripheral vision has such low resolution, one might wonder why we don’t see the world in a kind of tunnel vision where everything is out of focus except what we are directly looking at now. Instead, we seem to see our surroundings sharply and clearly all around us. We experience this illusion because our eyes move rapidly and constantly about three times per second even when we don’t realize it, focusing our fovea on selected pieces of our environment. Our brain fills in the rest in a gross, impressionistic way based on what we know and expect. 1 Our brain does not have to maintain a high-resolution mental model of our environment because it can order the eyes to sample and resample details in the environment as needed (Clark, 1998).

如果我们的周边视觉分辨率这么低,人们可能会想为什么我们不会看到隧道视野,除了我们现在直接看着的东西,其他一切都模糊不清。相反,我们似乎能清晰地看到我们周围的周围。我们体验这种错觉是因为我们的眼睛即使在没意识到的情况下也会快速不断地移动,每秒大约移动三次,把我们的中央凹聚焦在我们环境中的选定部分。我们的大脑以粗略、写意的方式填充剩余部分,根据我们所知和所期望的。1 我们的大脑不必保持环境的高分辨率心理模型,因为它可以命令眼睛根据需要采样和重新采样环境中的细节(Clark,1998)。

For example, as you read this page, your eyes dart around, scanning and reading. No matter where on the page your eyes are focused, you have the impression of viewing a complete page of text because, of course, you are.

例如,当你阅读这一页时,你的眼睛四处扫视,扫读。无论你的眼睛聚焦在页面的哪个位置,你都有观看完整文本页面的印象,因为当然你是在看。

But now imagine this: you are viewing the page on a computer screen. The computer is tracking your eyes and knows where your fovea is focused. The computer shows the correct text for that spot, but everywhere else the computer shows random meaningless text. As your fovea zips around the page, the computer instantly updates each area where your fovea pauses to show the correct text there, while the previous position of your fovea returns to textual noise. Amazingly, experiments have shown that people rarely notice this: not only can they read, they believe that they are viewing a full page of meaningful text (Clark, 1998). However, it does slow people’s reading even if they don’t realize it (Larson, 2004).

但现在想象一下:你在电脑屏幕上查看页面。电脑正在追踪你的眼睛,知道你的视锥细胞聚焦在哪里。电脑显示该位置的正确文本,但在其他地方显示随机无意义的文本。当你的视锥细胞在页面上快速移动时,电脑会立即更新你视锥细胞暂停的位置以显示正确文本,而之前视锥细胞的位置则返回到文本噪音。令人惊讶的是,实验表明人们很少注意到这一点:他们不仅能阅读,还相信他们正在观看一整页有意义的文本(Clark,1998)。然而,即使他们没有意识到,这也确实会减慢人们的阅读速度(Larson,2004)。

Perhaps the best demonstration that our peripheral vision does not see as much detail as our foveal vision is Ninio’s Extinction Illusion (see Fig. 5.3). Try to count the dots. Only dots that are in the center of your visual field are visible even though the entire grid appears to be in sharp focus. This shows that what we perceive as high-resolution peripheral vision is actually an artificial construction of our visual system filling in what it expects to be there.

也许,我们周边视觉并不像中心视觉那样能看清细节的最佳证明是尼尼奥的消逝错觉(见图 5.3)。试着数一下点。只有位于你视野中心的点才是可见的,尽管整个网格看起来都很清晰。这表明我们感知为高分辨率周边视觉实际上是我们视觉系统的一种人为构造,它填补了它预期存在的地方。

The fact that retinal cone cells are distributed tightly in and near the fovea, and sparsely in the periphery of the retina, affects not only spatial resolution but also color resolution. We can discriminate colors better in the center of our visual field than at the edges.

视网膜中心凹附近的视锥细胞密集分布,而视网膜周边稀疏分布,这不仅影响空间分辨率,也影响颜色分辨率。我们在视野中心比在边缘更能区分颜色。

Another interesting fact about our visual field is that it has a gap— a small area (blind spot) in which we see nothing. The gap corresponds to the spot on our retina where the optic nerve and blood vessels exit the back of the eye (see Fig. 5.1). There are no retinal rod or cone cells at that spot, so when the image of an object in our visual field happens to fall on that part of the retina, we don’t see it. We usually don’t notice this hole in our vision because our brain fills it in with the surrounding content, like a graphic artist using Photoshop to fill in a blemish on a photograph by copying nearby background pixels.

关于我们的视觉场,一个有趣的事实是它有一个缺口——一个小区域(盲点),我们在这个区域什么也看不见。这个缺口对应着我们视网膜上视神经和血管从眼睛后部出来的地方(见图 5.1)。在这个点上没有视网膜视杆或视锥细胞,所以当我们在视觉场中的物体图像恰好落在视网膜的这个部分时,我们就看不见它。我们通常不会注意到我们视野中的这个洞,因为大脑会用周围的内容来填补它,就像一位图形艺术家使用 Photoshop 通过复制附近的背景像素来填补照片上的瑕疵一样。

People sometimes experience the blind spot when they gaze at stars. As you look at one star, a nearby star may disappear briefly into the blind spot until you shift your gaze. You can also observe the gap by trying the exercise in Fig. 5.4. Some people have other gaps resulting from imperfections on the retina, retinal damage, or brain strokes that affect the visual cortex, 2 but the optic nerve gap is an imperfection everyone shares.

人们有时在凝视星星时会体验到盲点。当你看着一颗星星时,一颗附近的星星可能会暂时消失在盲点中,直到你转移视线。你也可以通过尝试图 5.4 中的练习来观察这个缺口。有些人有其他缺口,这是由于视网膜上的缺陷、视网膜损伤或影响视觉皮层的脑卒中造成的,但视神经缺口是每个人都会有的缺陷。

Is the Visual Periphery Good for Anything?

视觉周边区域有什么用?

It seems that the fovea is better than the periphery at just about everything. One might wonder why we have peripheral vision. What is it good for? Our peripheral vision serves three important functions: it guides our fovea toward objects and events that match our goals, it detects motion and guides our fovea there, and it lets us see better in the dark.

看起来,中央凹在几乎所有方面都比周边视觉更好。人们可能会想,我们为什么有周边视觉?它有什么用?我们的周边视觉有三个重要作用:它引导中央凹朝向与我们的目标相匹配的物体和事件,它检测运动并引导中央凹到那里,它还让我们在黑暗中看得更清楚。

Function 1: guides fovea toward objects matching goals

功能 1:引导视网膜中央凹朝向与目标匹配的物体

Remember what Chapter 1 explained: our perception is biased by our goals. Peripheral vision provides low-resolution cues to guide our eye movements so that our fovea visits the interesting and crucial parts of our visual field. Our eyes don’t scan our environment randomly. They move so as to focus our fovea on important things—things related to our goals and to possible threats —the most important ones (usually) first. Think of peripheral vision as our visual system’s “forward patrol,” primed to notice important things and report them to “central command.” Thus, the fuzzy cues in the periphery of our visual field provide the data that helps our brain plan where to move our eyes and attention.

记住第一章所解释的:我们的感知受到我们目标的影响。周边视觉提供低分辨率的线索来引导眼球运动,以便中央凹访问我们视觉场中有趣和关键的部分。我们的眼睛不会随机扫描环境。它们移动是为了将中央凹聚焦在重要的事情上——与我们的目标和可能的威胁相关的事情——通常是首先关注最重要的事情。把周边视觉想象成我们视觉系统的“前沿巡逻队”,随时准备注意到重要的事情并向“中央指挥官”报告。因此,我们视觉场周边的模糊线索为我们的大脑提供了数据,帮助大脑计划眼球和注意力的移动位置。

For example, when we scan a medicine label for a “use by” date, a fuzzy blob in the periphery with the vague form of a date is enough to cause an eye movement that lands the fovea there to allow us to check it. If we are browsing a produce market looking for strawberries, a blurry reddish patch at the edge of our visual field draws our eyes and our attention, even though sometimes it will be radishes instead of strawberries. If we hear an animal growl nearby, a fuzzy animal-like shape in the corner of our eye will be enough to zip our eyes in that direction, especially if the shape is moving toward us (see Fig. 5.5). And as shown in Chapter 1, where we look on a web page or app screen depends on what on the display matches our goals.

例如,当我们扫描药品标签上的“有效期”时,外围模糊不清、形状模糊的日期足以引起眼球运动,使我们的视锥细胞聚焦在那里以进行检查。如果我们正在逛农产品市场寻找草莓,视野边缘模糊的红色斑块会吸引我们的眼球和注意力,即使有时那其实是小萝卜而不是草莓。如果我们听到附近有动物低吼,视野角落里模糊的动物形状就足以让我们的眼睛迅速转向那个方向,特别是当那个形状向我们移动时(见图 5.5)。正如第一章所示,我们在网页或应用程序屏幕上注视哪里取决于显示内容与我们的目标是否匹配。

FIGURE 5.5A moving shape at the edge of our vision draws our eye: it could be food, or it might consider us food.

图 5.5 视野边缘的移动形状会吸引我们的眼球:它可能是食物,也可能把我们当作食物。

How peripheral vision guides and augments central, foveal vision is discussed more in the “Visual Search is Linear Unless Targets ‘Pop’ in the Periphery” section later in this chapter.

外围视觉如何引导和增强中心视锥细胞视觉将在本章后面的“视觉搜索是线性的,除非目标在边缘‘突出’”部分进行更详细的讨论。

Function 2: detects motion

功能 2:检测运动

A related guiding function of peripheral vision is that it is good at detecting motion. Anything that moves in our visual periphery, even slightly, is likely to draw our attention—and hence our fovea— toward it. The reason for this phenomenon is that our ancestors— including prehuman ones—were selected for their ability to spot food and avoid predators. As a result, even though we can move our eyes under conscious, intentional control, some of the mechanisms that control where our eyes look are preconscious, involuntary, and very fast.

边缘视觉的一个相关引导功能是它擅长检测运动。我们视野边缘的任何移动,即使是轻微的,也可能会吸引我们的注意力——进而吸引我们的中央凹。这种现象的原因是,我们的祖先——包括类人祖先——被选择出来是因为他们能够发现食物和躲避捕食者。因此,尽管我们可以通过有意识、有目的的控制来移动眼睛,但控制眼睛看向哪里的某些机制是前意识的、无意识的,而且非常快。

What if we have no reason to expect that there might be anything interesting in a certain spot in the periphery, 3 and nothing in that spot attracts our attention? Our eyes may never move our fovea to that spot, so we may never see what is there.

如果我们没有任何理由期待某个视野边缘的特定位置可能有什么有趣的东西,3 并且那个位置没有任何东西吸引我们的注意力呢?我们的眼睛可能永远不会移动中央凹到那个位置,因此我们可能永远不会看到那里有什么。

Function 3: lets us see better in the dark

功能 3:让我们在黑暗中看得更清楚

A third function of peripheral vision is to allow us to see in low-light conditions—for example, on starlit nights, in caves, around campfires, etc. These were conditions under which vision evolved and in which people—like the animals that preceded them on Earth —spent much of their time until the invention of the electric light bulb in the 1800s.

边缘视觉的第三个功能是让我们能够在低光照条件下看东西——例如,在星光璀璨的夜晚、洞穴中、篝火周围等。这些是视觉进化的环境,也是人类——以及他们在地球上的前驱动物——在发明电灯泡之前的很长时间里花费大量时间的环境。

Just as the rods are less functional in well-lighted conditions (see Chapter 4), the cones don’t function very well in low light, so our rods take over. Low-light, rods-only vision is called scotopic vision. An interesting fact is that because there are no rods in the fovea, you can see objects better in low-light conditions (e.g., faint stars) if you don’t look directly at them.

正如棒状体在强光条件下功能较弱(见第 4 章),视锥细胞在弱光下也不太起作用,因此我们的棒状体会接管工作。弱光下仅由棒状体负责的视觉称为暗视觉。一个有趣的事实是,由于中央凹处没有棒状体,如果你不直接盯着看,在弱光条件下(例如微弱的星星)你能看得更清楚。

Examples From Computer User Interfaces

来自计算机用户界面的例子

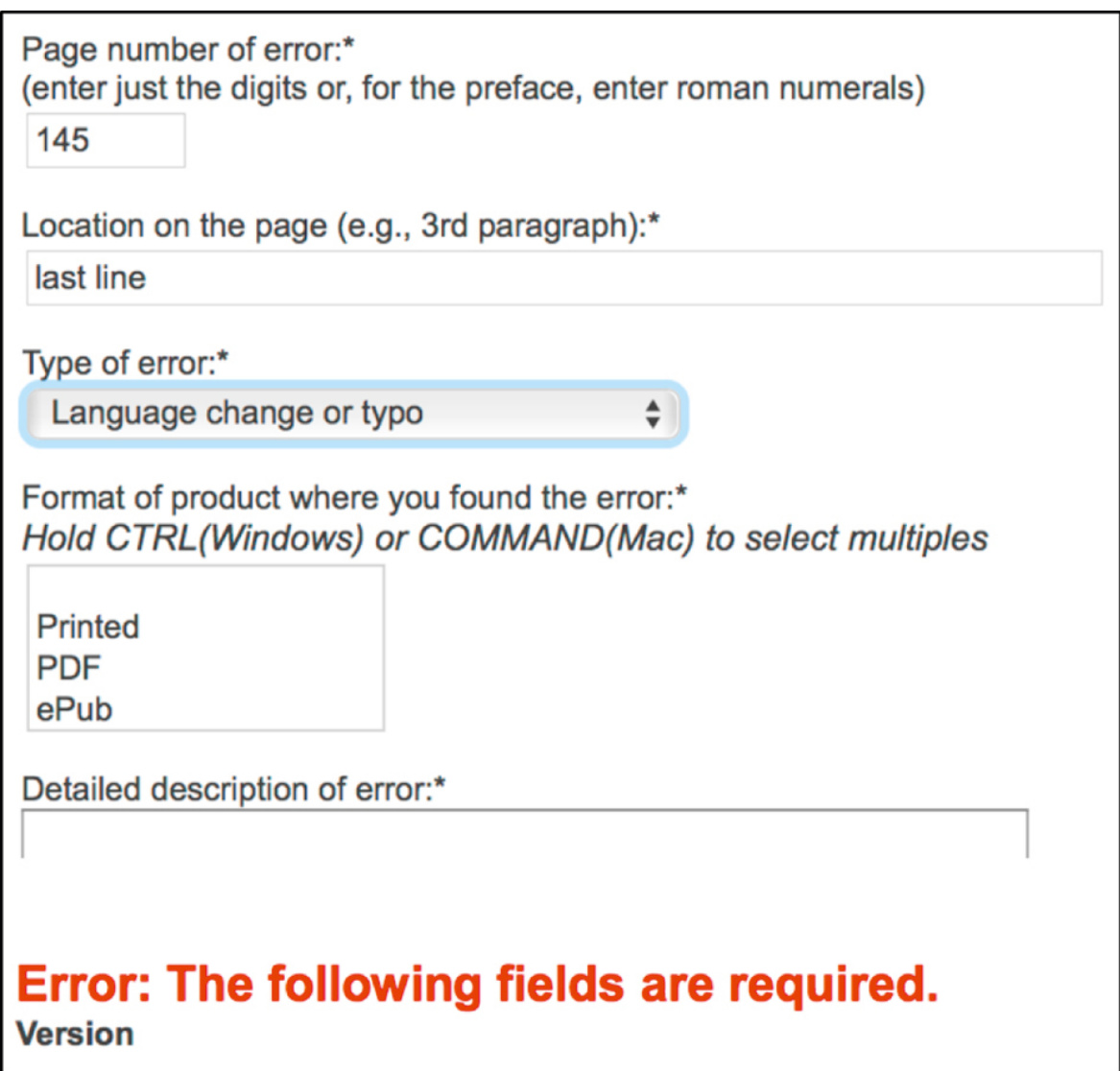

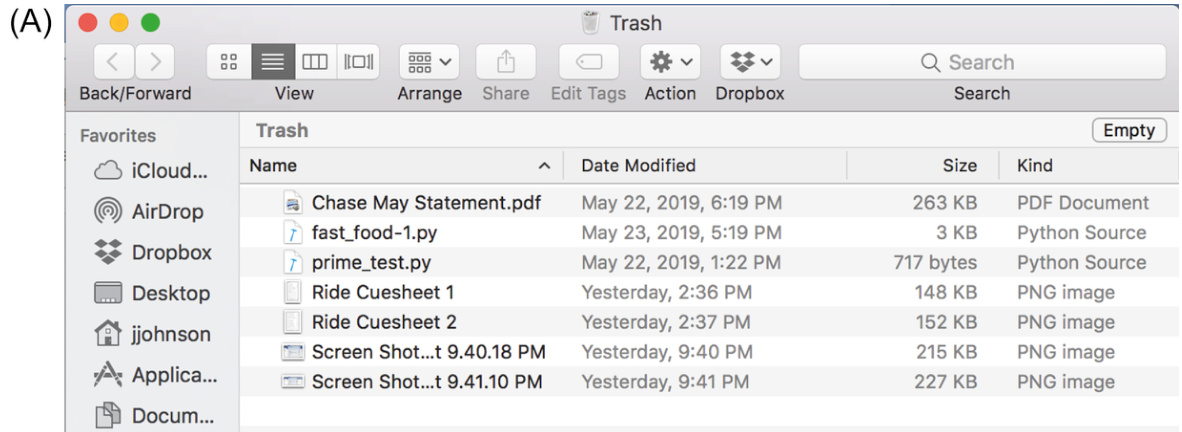

The low acuity of our peripheral vision explains why users of software and websites fail to notice error messages in some applications and websites. When someone clicks a button or link, that is usually where his or her fovea is positioned. Everything on the screen not within 1–2 cm of the click location (assuming a normal computer viewing distance) is in peripheral vision, where resolution is low. If after the click, an error message appears in the periphery, it should not be surprising if the person does not notice it.

我们周边视觉的分辨率较低解释了为什么软件和网站的用户有时会忽略某些应用程序和网站中的错误消息。当某人点击按钮或链接时,他的或她的中央凹通常位于那里。屏幕上距离点击位置 1-2 厘米以外的所有内容(假设正常的计算机观看距离)都在周边视觉中,分辨率较低。如果在点击后,错误消息出现在周边视觉中,如果用户没有注意到它,也就不足为奇了。

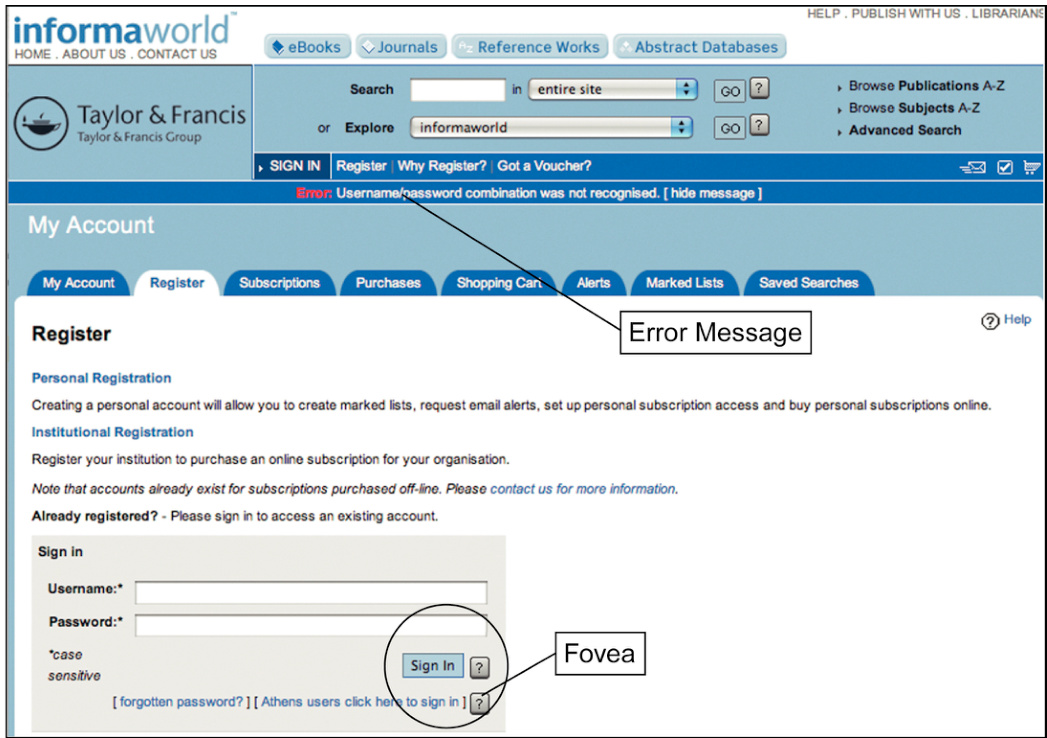

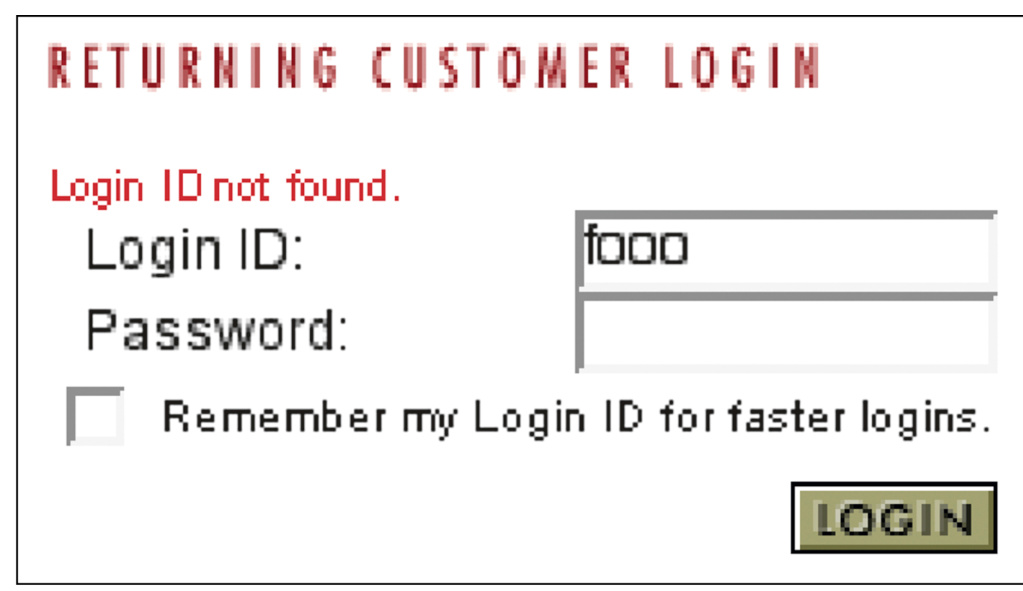

For example, at Informaworld.com, the former online publication website of Informa Healthcare, if a user entered an incorrect username or password and clicked “Sign In,” an error message appeared in a “message bar” far away from where the users’ eyes were most likely focused (see Fig. 5.6). The red word “Error” might appear in the user’s peripheral vision as a small reddish blob, which would help draw the eyes in that direction. However, the red blob might fall into a gap in the viewer’s visual field and not be noticed at all.

例如,在 Informaworld.com 上,即前 Informaworld Healthcare 的在线出版物网站,如果用户输入了错误的用户名或密码并点击“登录”,错误消息会出现在远离用户最可能注视位置的“消息栏”(见图 5.6)。红色的“错误”字样可能会出现在用户的周边视觉中,形成一个微小的红色光斑,从而吸引视线朝那个方向看。然而,这个红色光斑可能会落在观察者视野的间隙中,完全不被注意到。

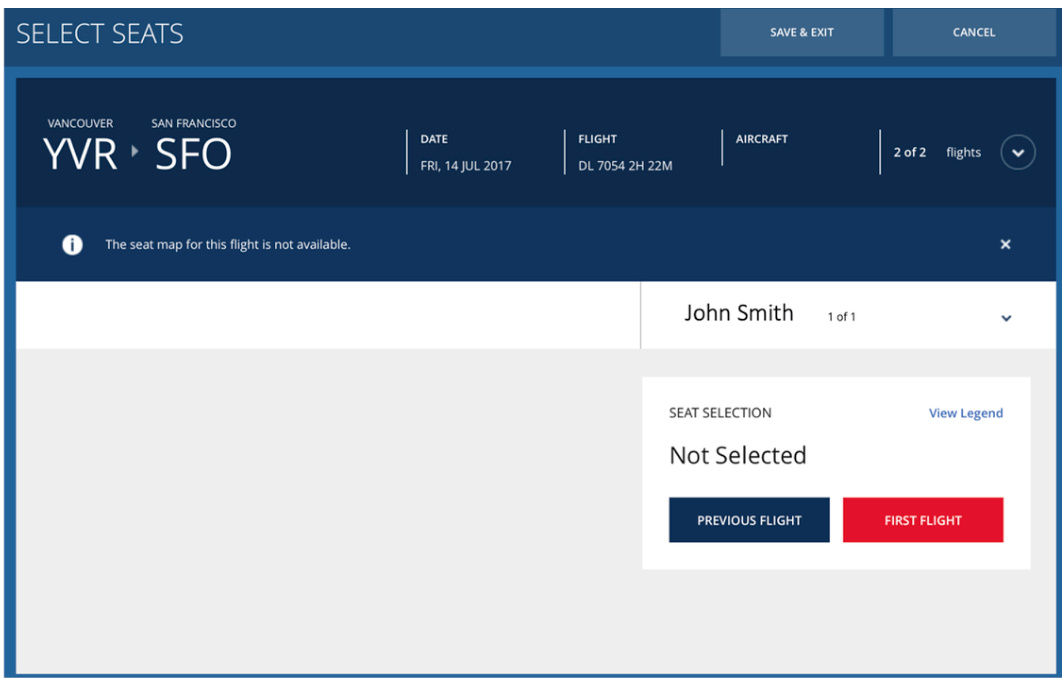

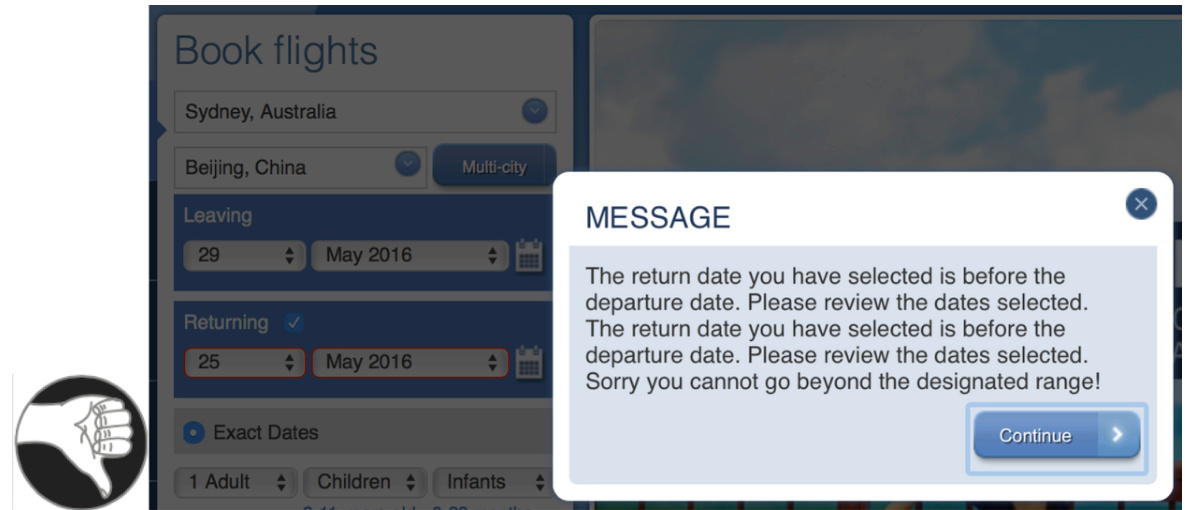

An alert message displayed by Delta Airlines’ (2017) website is similarly easy to miss (see Fig. 5.7). Customers sometimes encountered it when clicking through seat-selection steps of the flight check-in process. Users’ attention almost certainly would be focused on the Previous Flight/First Flight buttons at the lower right of the screen. The alert message is not as far from where site visitors would be looking as for the one at Informaworld.com, but it is tiny and insufficiently highlighted.

灰度航空公司(2017)网站显示的警告消息同样容易被忽略(见图 5.7)。顾客有时在点击航班登机过程的座位选择步骤时会遇到它。用户的注意力几乎肯定会集中在屏幕右下角的“上一个航班/第一个航班”按钮上。与 Informaworld.com 上的警告消息相比,这个警告消息离网站访客注视的位置没有那么远,但它太小且不够突出。

Consider the sequence of events from a user’s point of view. The user enters a username and password and then clicks “Sign In.” The page redisplays with blank fields. The user thinks “Huh? I gave it my login information and hit ‘Sign In,’ didn’t I? Did I hit the wrong button?” The user reenters the username and password and clicks “Sign In” again. The page redisplays with empty fields again. Now the user is really confused. The user sighs (or curses), sits back in his chair, and lets his eyes scan the screen. Suddenly noticing the error message, the user says “A-ha! Has that error message been there all along?”

从用户的角度来看,考虑事件序列。用户输入用户名和密码,然后点击“登录”。页面重新显示空白字段。用户想:“哈?我输入了登录信息并点击了‘登录’,对吧?我是否按错了按钮?”用户再次输入用户名和密码,然后再次点击“登录”。页面再次重新显示空白字段。现在用户真的困惑了。用户叹了口气(或者诅咒),坐在椅子上,让他的眼睛扫过屏幕。突然注意到错误消息,用户说:“啊哈!这个错误消息一直都在吗?”

FIGURE 5.6The error message from the former Taylor & Francis Informaworld website (2010) for a faulty login appeared in peripheral vision, where most users would probably not see it.

图 5.6 显示了前 Taylor & Francis Informaworld 网站在 2010 年针对登录错误的错误消息,它出现在大多数用户可能不会看到的外围视觉中。

FIGURE 5.7 Error message at Delta.com (2017). Can you spot it?

图 5.7 Delta.com(2017 年)的错误消息。你能找到它吗?

FIGURE 5.8 This error message for an invalid login was easy to miss even though it is not far from the “Login” button. Why?

图 5.8 这个无效登录的错误消息很容易被忽略,尽管它离“登录”按钮不远。为什么?

FIGURE 5.9Simulation of a user’s visual field while the fovea is fixed on the “Login” button.

图 5.9 模拟用户在视锥固定于“登录”按钮时的视野。

Even when an error message is placed nearer to the center of the viewer’s visual field than in the preceding examples, other factors can diminish its visibility. For example, from about 2003 to2008, 4 the website of Airborne Express (now part of DHL) signaled a login failure by displaying an error message in red just above the Login ID field (see Fig. 5.8). The error message was entirely in red and fairly near the “Login” button where a user’s eyes and attention would be focused. Can you think of any reasons people might not initially see it?

即使错误信息放置在比前述例子更靠近观众视野中心的位置,其他因素也可能降低其可见性。例如,从 2003 年到 2008 年,4 Airborne Express(现已成为 DHL 的一部分)的网站通过在登录 ID 字段上方以红色显示错误信息来指示登录失败(见图 5.8)。错误信息完全是红色的,并且靠近“登录”按钮,用户的眼睛和注意力会集中在那里。你能想到人们可能最初看不到它的任何原因吗?

One reason is that the error message was still in peripheral vision, not the fovea. The fovea is small: just a centimeter or two on a computer screen, assuming the user is a normal distance from the screen.

一个原因是错误信息仍然在周边视觉中,而不是在视锥中。视锥很小:在计算机屏幕上只有一厘米或两厘米,假设用户与屏幕的距离是正常的。

A second reason is that the error message was not the only red thing near the top of the page. The page title was also red. Resolution in the periphery is very low. When the error message appeared, a user’s peripheral vision might not register any change— there was a red blotch there before, and with the error message, there still was (see Fig. 5.9).

第二个原因是,页面顶部附近的红色东西不只是错误消息。页面标题也是红色的。周边视觉的分辨率非常低。当错误消息出现时,用户的周边视觉可能不会察觉到任何变化——之前那里有一个红色污点,出现错误消息后仍然如此(见图 5.9)。

If the page title were black or any other color besides red, the red error message would be more likely to be noticed, even though it appeared in the periphery of the user’s visual field.

如果页面标题是黑色或其他颜色而不是红色,即使错误消息出现在用户视觉场的周边,也更有可能被注意到。

Common Methods of Making Messages Visible

使信息可见的常用方法

Several common and well-known methods can ensure that error messages are seen:

有几种常见且众所周知的方法可以确保错误消息被看到:

• Put it where users are looking . People focus on predictable places when interacting with graphical user interfaces. In Western societies, people tend to traverse forms and control panels from upper left to lower right. While moving the screen pointer, people usually look either at where it is or where they are moving it to. When people click a button or link, they can usually be assumed to be looking directly at it, at least for a few moments afterward. Designers can use this predictability to position error messages near where they expect users to be looking.

• 放置在用户注视的地方。人们在交互图形用户界面时,会集中在可预测的地方。在西方社会,人们倾向于从左上角到右下角浏览表单和控制面板。当移动屏幕指针时,人们通常会看着指针所在的位置或将要移动的位置。当人们点击按钮或链接时,通常可以假设他们直接看着它,至少在之后的一段时间内是这样。设计师可以利用这种可预测性来定位错误消息在他们预期用户会注视的地方。

• Mark the error . Somehow, mark the error prominently to indicate clearly that something is wrong. Often this can be done by simply placing the error message near what it refers to, unless that would place the message too far from where users are likely to be looking.

• 标记错误。以某种方式突出显示错误,清楚地表明存在问题。通常可以通过将错误消息放置在它所引用的内容附近来完成,除非这样做会将消息放置在用户不太可能查看的位置。

• Use an error symbol . Make errors or error messages more visible by marking them with an error symbol, such as ,

• 使用错误符号。通过使用错误符号(如)使错误或错误消息更加醒目。

• Reserve red for errors . By convention, interactive computer systems use the color red to connote alert, danger, error, etc. Using red for any other information on a computer display risks misinterpretation. But suppose you are designing a website for Stanford University, which has red as its school color. Or suppose you are designing for a Chinese market, where red is considered an auspicious, positive color. What do you do? Use another color for errors, mark them with error symbols, or use stronger methods (see the next section).

• 将红色保留用于错误。根据惯例,交互式计算机系统使用红色来表示警报、危险、错误等。在计算机显示器上使用红色用于任何其他信息可能会导致误解。但假设您正在为斯坦福大学设计网站,红色是其学校颜色。或者假设您正在为中国市场设计,在那里红色被视为吉祥、积极的颜色。您该怎么办?为错误使用另一种颜色,使用错误符号,或使用更强的方法(见下一节)。

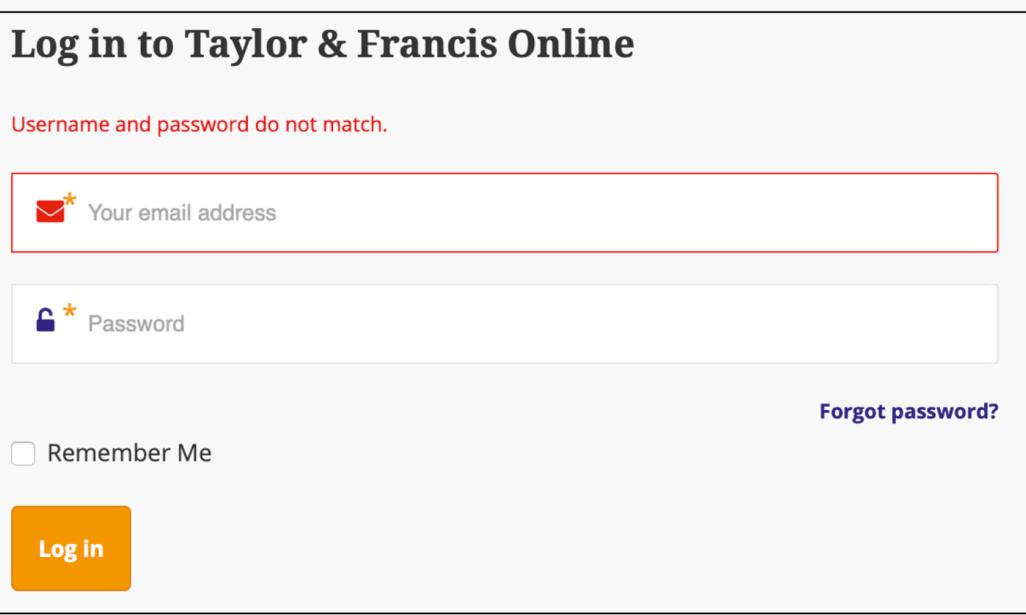

The most recent Taylor & Francis login error screen uses several of these techniques (see Fig. 5.10). Compare it with their earlier website (see Fig. 5.6). A bigger, bolder font for the error message and an error symbol would improve this, but it is much better than in the 2010 site.

最新的 Taylor & Francis 登录错误屏幕使用了这些技术中的几种(见图 5.10)。将其与他们的早期网站(见图 5.6)进行比较。更大的、更粗的字体用于错误消息和错误符号将改进这一点,但比 2010 年的网站好得多。

FIGURE 5.10 In the latest Taylor & Francis website (2020), the error message for a faulty login is displayed near where users will be looking, and both the error message and the login field are highlighted in red (compare with Fig. 5.6).

图 5.10 在最新的 Taylor & Francis 网站(2020 年),故障登录的错误消息显示在用户将查看的位置附近,并且错误消息和登录字段都标红(与图 5.6 比较)。

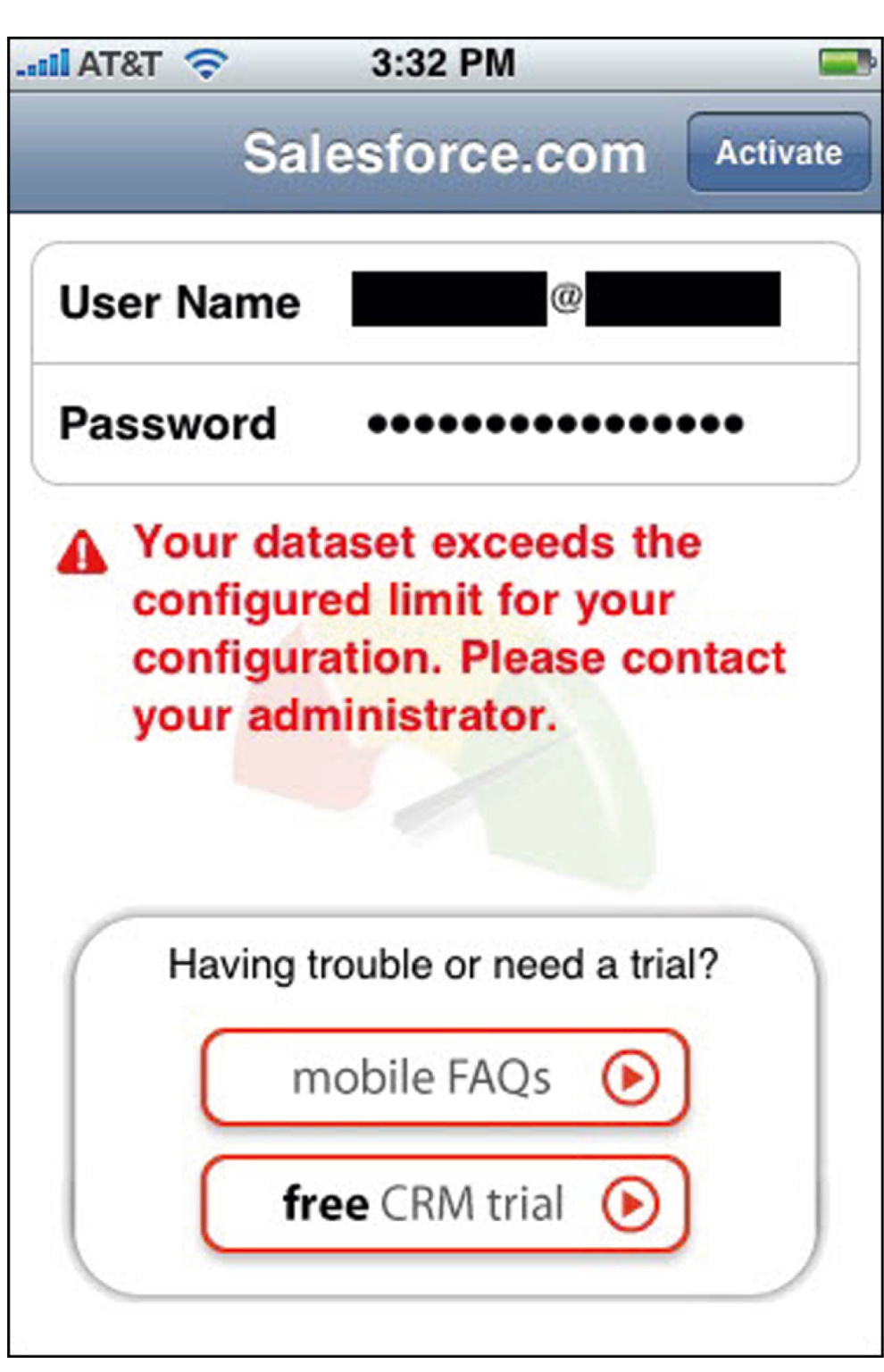

FIGURE 5.11Salesforce.com’s mobile site displays error messages prominently, midscreen.

图 5.11 Salesforce.com 的移动网站突出显示错误消息,屏幕中间。

Salesforce.com’s mobile app displays error messages in a way that makes them hard to miss (see Fig. 5.11). They are marked with an error symbol and displayed in red in the middle of the screen.

Salesforce.com 的移动应用程序以难以忽视的方式显示错误消息(见图 5.11)。它们带有错误符号,并以红色显示在屏幕中央。

Heavy Artillery for Making Users Notice Messages

用于让用户注意信息的重火力

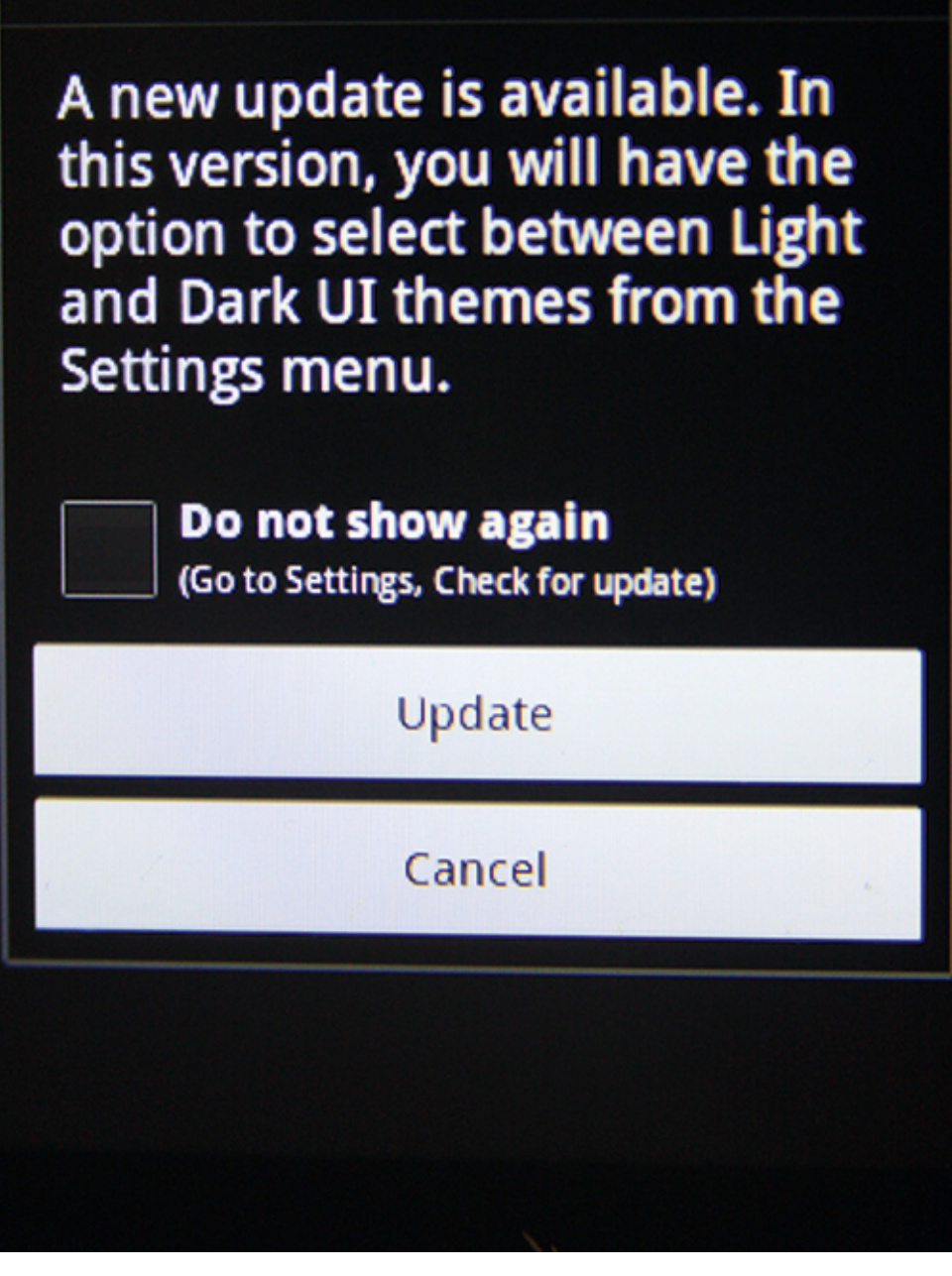

If the common, conventional methods of making users notice messages are not enough, three stronger methods are available to user-interface designers: a pop-up message in an error dialogue box, use sound (e.g., a beep), and wiggle or blink briefly. However, these methods, while very effective, have significant negative effects, so they should be used sparingly and with great care.

如果使用户注意到消息的常用、常规方法不够,用户界面设计师可以采用三种更强的方法:在错误对话框中显示弹出消息、使用声音(例如,发出哔哔声),以及短暂地抖动或闪烁。然而,虽然这些方法非常有效,但它们有显著的负面影响,因此应该谨慎地少量使用。

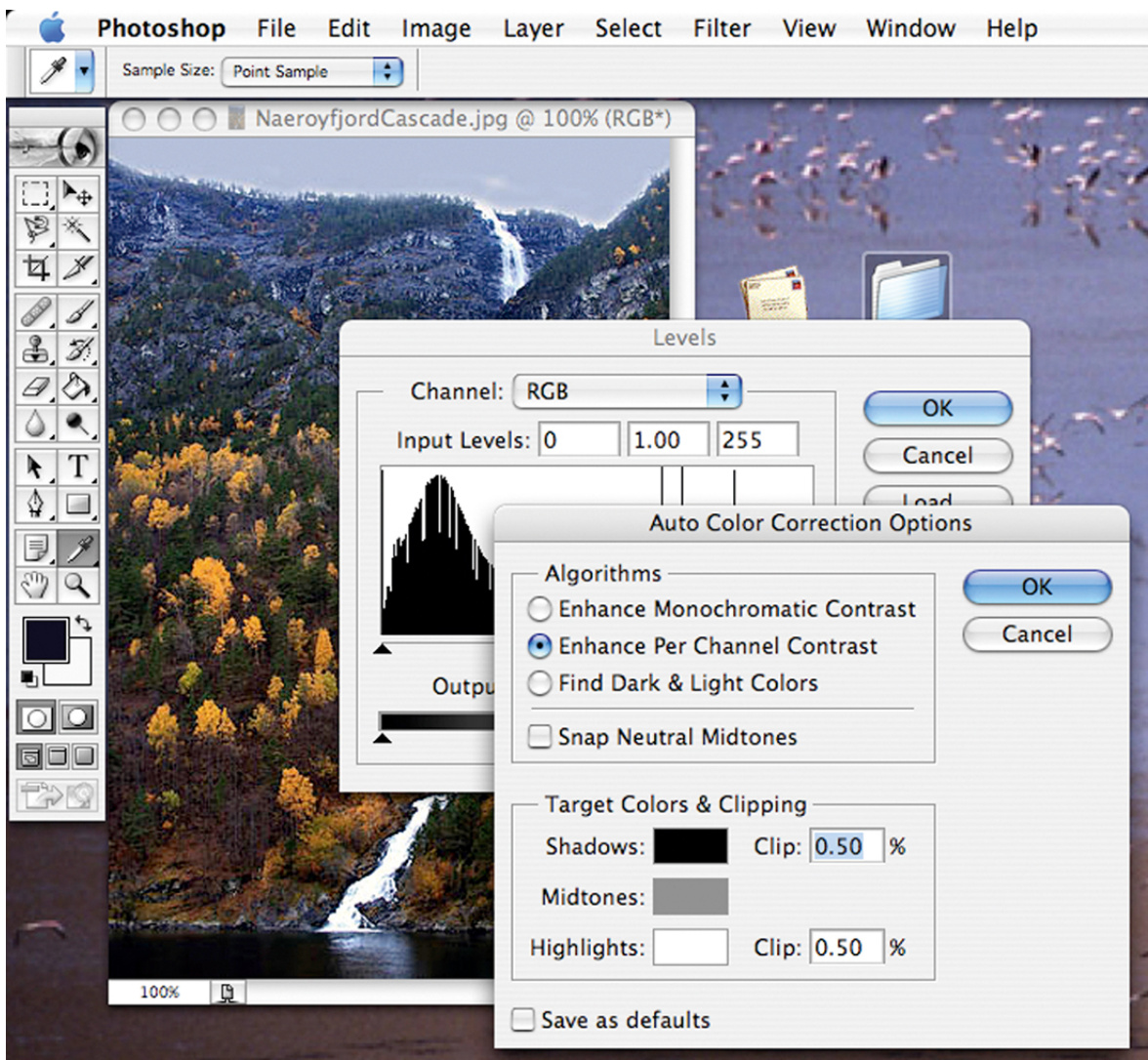

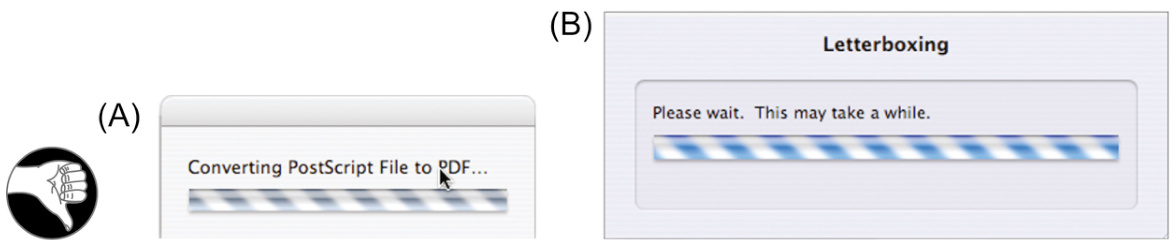

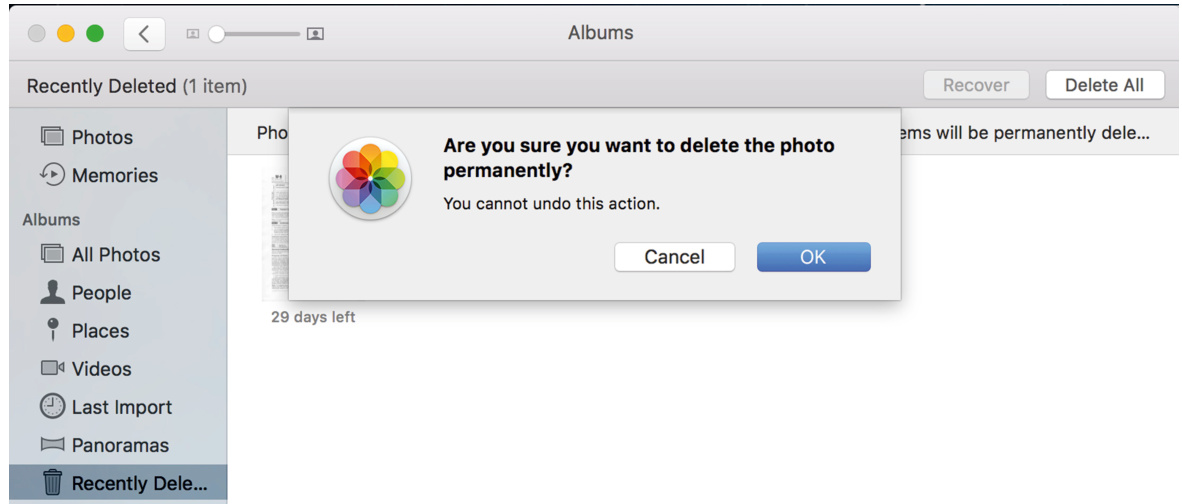

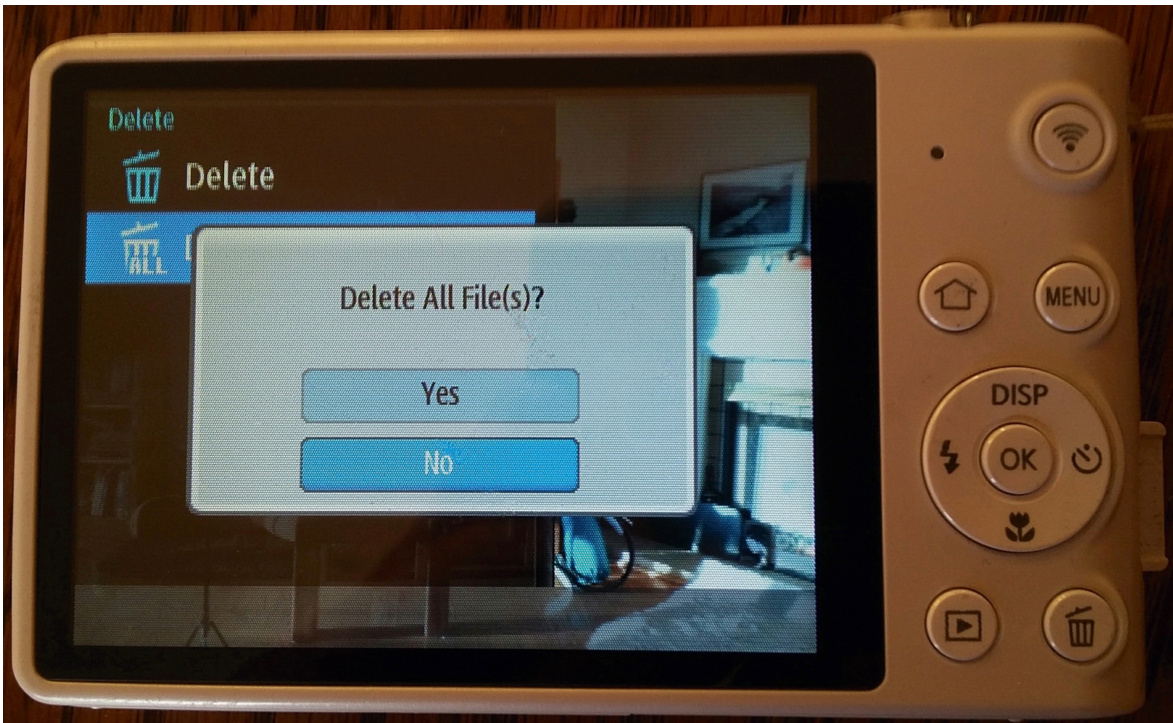

Method 1: a pop-up message in an error dialogue box

方法 1:在错误对话框中显示弹出消息

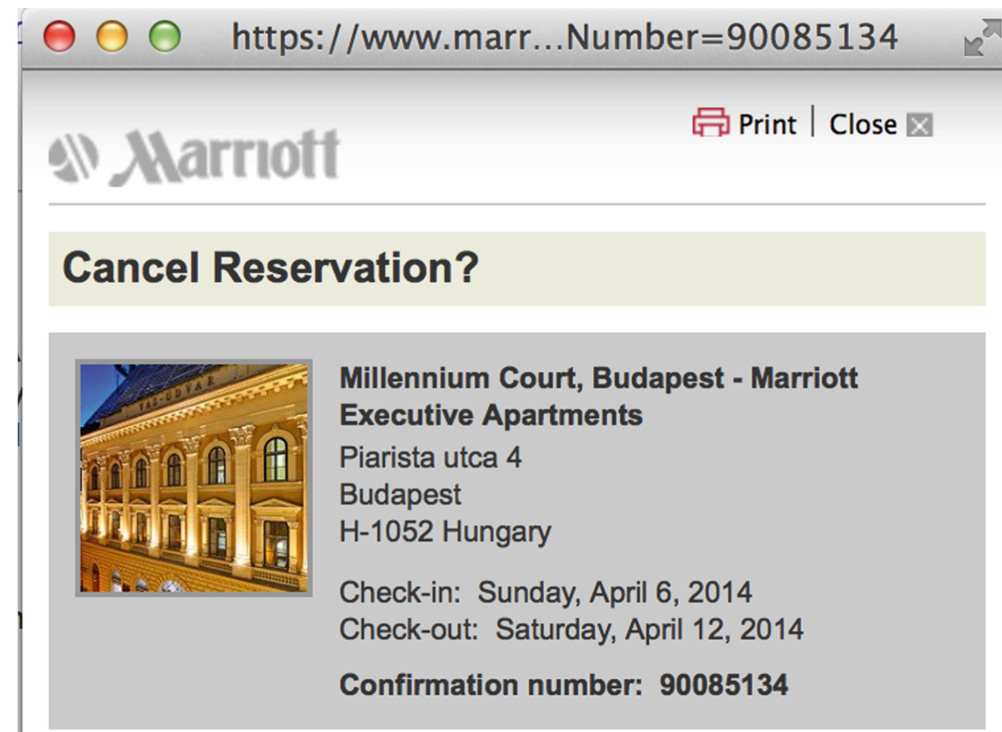

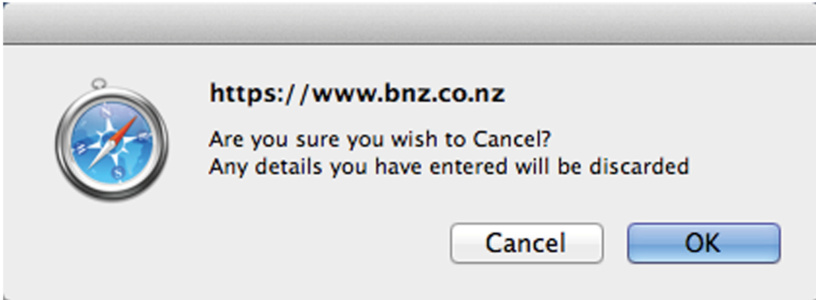

Displaying an error message in a dialogue box sticks it right in the user’s face, making it hard to miss. Error dialogue boxes interrupt the user’s work and demand immediate attention. That is good if the error message signals a critical condition, but it can annoy people if such an approach is used for a minor message, such as confirming the execution of a user-requested action.

在对话框中显示错误消息会直接出现在用户面前,很难被忽略。错误对话框会中断用户的工作并要求立即注意。如果错误消息表示关键情况,这是好的,但如果这种做法用于确认用户请求执行的小消息,则可能会让人烦恼。

The annoyance of pop-up messages rises with the degree of modality. Nonmodal pop-ups allow users to ignore them and continue working. Application-modal pop-ups block any further work in the application that displayed the error but allow users to interact with other software on their computer. System-modal pop-ups block any user action until the dialogue has been dismissed.

弹出消息的烦恼程度随着模态度的增加而增加。非模态弹出消息允许用户忽略它们并继续工作。应用程序模态弹出消息会阻止在显示错误的应用程序中的任何进一步工作,但允许用户与计算机上的其他软件交互。系统模态弹出消息会阻止任何用户操作,直到对话框被关闭。

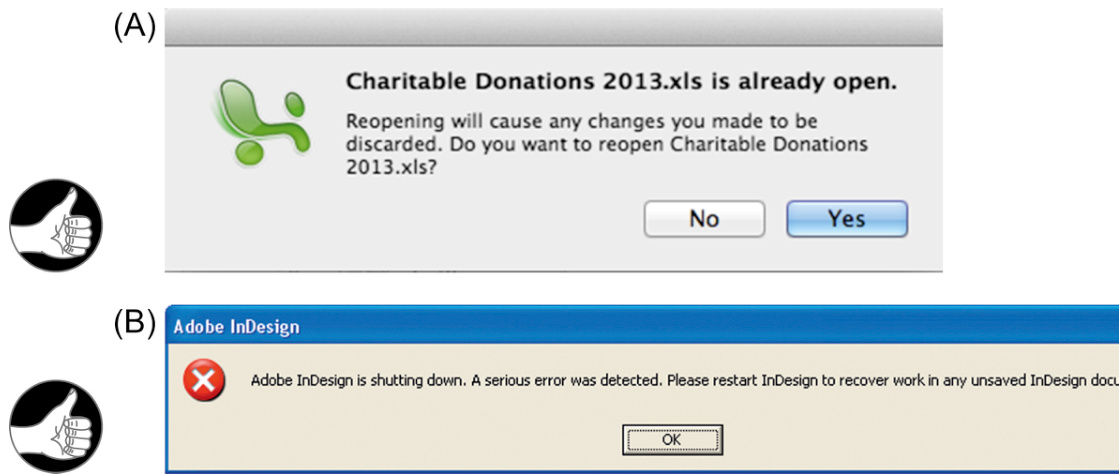

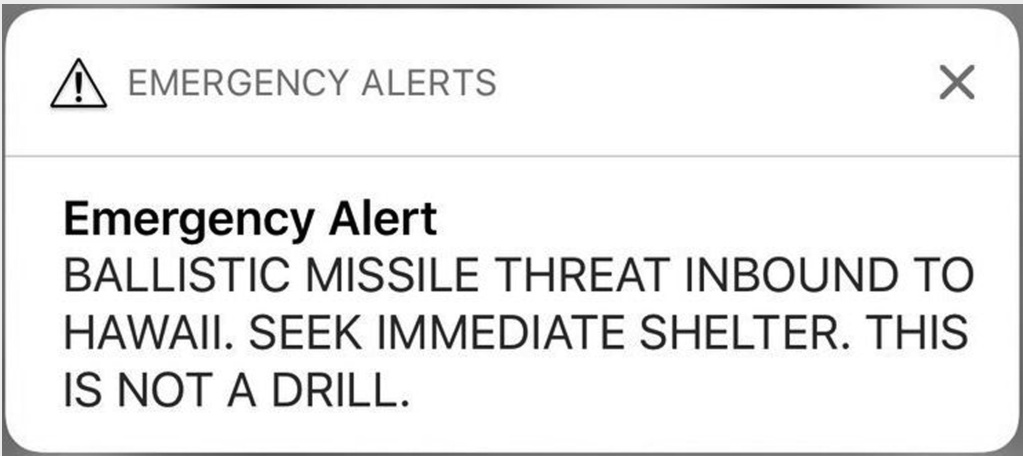

Application-modal pop-ups should be used sparingly—for example, only when application data may be lost if the user doesn’t attend to the error. System-modal pop-ups should be used extremely rarely—basically only when the system is about to crash, taking hours of work with it, or if people will die if the user misses the error message.

应用程序模态弹窗应谨慎使用——例如,仅在用户未注意错误可能导致应用程序数据丢失时使用。系统模态弹窗应极其罕见地使用——基本上仅在系统即将崩溃,导致数小时的工作丢失,或者如果用户错过错误信息会导致人员伤亡时使用。

On the Web, an additional reason to avoid pop-up error dialogue boxes is that some people set their browsers to block all pop-up windows. If your website relies on pop-up error messages, some users may never see them.

在网页上,避免使用弹窗错误对话框的另一个原因是,有些人将他们的浏览器设置为阻止所有弹窗窗口。如果你的网站依赖于弹窗错误消息,一些用户可能永远不会看到它们。

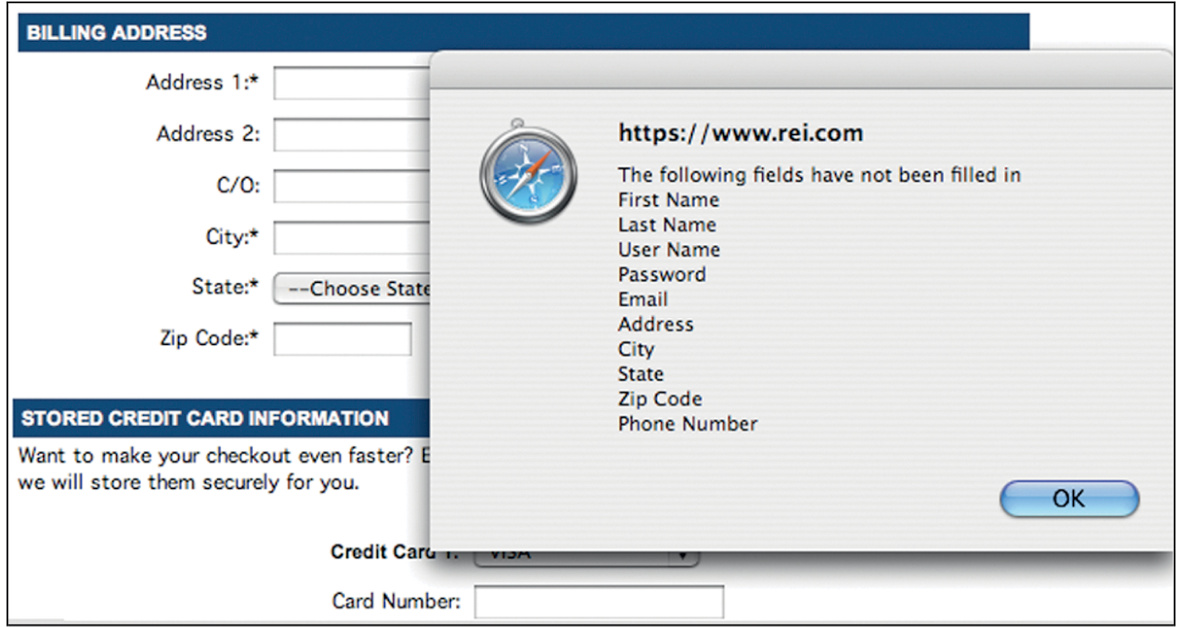

REI.com has an example of a pop-up dialogue being used to display an error message. The message is displayed when someone who is registering as a new customer omits any required field in the form (see Fig. 5.12). Is this an appropriate use of a pop-up dialogue? The improved Taylor & Francis error message display (see Fig. 5.10) shows that data entry errors can be signaled well without pop-up dialogues, so REI.com’s use of them seems a bit heavy-handed.

REI.com 有一个使用弹窗对话框显示错误消息的例子。当新客户在注册表单中遗漏任何必填字段时,会显示该消息(见图 5.12)。这是使用弹窗对话框的适当用法吗?改进的 Taylor & Francis 错误消息显示(见图 5.10)表明,无需弹窗对话框就可以很好地指示数据输入错误,因此 REI.com 对它们的使用似乎有点过于强硬。

Examples of more appropriate use of error dialogue boxes come from Microsoft Excel (see Fig. 5.13A) and Adobe InDesign (see Fig. 5.13B). In both cases, loss of data is at stake.

更适当的错误对话框使用例子来自 Microsoft Excel(见图 5.13A)和 Adobe InDesign(见图 5.13B)。在这两种情况下,都涉及数据丢失的风险。

FIGURE 5.12 REI.com’s pop-up dialogue box signals required data that was omitted. It is hard to miss, but perhaps overkill.

图 5.12 REI.com 的弹出对话框提示遗漏了必要数据。它很难被忽视,但也许过于夸张。

FIGURE 5.13 Appropriate pop-up error dialogues: (A) Microsoft Excel and (B) Adobe InDesign.

图 5.13 适当的弹出错误对话框:(A) Microsoft Excel 和 (B) Adobe InDesign。

Method 2: use sound (e.g., a beep)

方法 2:使用声音(例如,蜂鸣声)

When a computer beeps, it tells its user something has happened that requires attention. The person’s eyes reflexively begin scanning the screen for whatever caused the beep. This can allow users to notice an error message someplace other than where they were just looking, such as in a standard error message box on the display. That is the value of beeping.

当计算机发出哔哔声时,它告诉用户发生了需要关注的事情。人们的眼睛会反射性地开始扫描屏幕,寻找发出哔哔声的原因。这可以让用户注意到错误消息,而不仅仅是在他们刚刚看的地方,比如显示器上的标准错误消息框。这就是哔哔声的价值。

However, imagine many people in a cubicle work environment or a classroom, all using an application that signals all errors and warnings by beeping. Such a workplace would be very annoying to say the least. Worse, people would not be able to tell whether their own computer or someone else’s was beeping.

然而,想象一下在隔间工作环境或教室里,许多人都在使用一个通过哔哔声来表示所有错误和警告的应用程序。这样的工作场所至少会非常烦人。更糟糕的是,人们将无法分辨是自己的计算机还是别人的计算机在哔哔。

The opposite situation is noisy work environments (e.g., factories or computer server rooms), where auditory signals emitted by an application might be masked by ambient noise. Even in nonnoisy environments, some computer users simply prefer quiet and mute the sound on their computers or turn it way down.

相反的情况是嘈杂的工作环境(例如工厂或计算机服务器室),其中应用程序发出的声音信号可能会被环境噪音所掩盖。即使在非嘈杂的环境中,一些计算机用户也简单地更喜欢安静,并在他们的计算机上关闭声音或将音量调得很低。

For these reasons, signaling errors and other conditions with sound are remedies that can be used only in very special, controlled situations.

由于这些原因,使用声音来指示错误和其他情况是只有在非常特殊、受控的情况下才能使用的补救措施。

Computer games often use sound to signal events and conditions. In games, sound isn’t annoying; it is expected. Its use in games is widespread, even in game arcades where dozens of machines are all banging, roaring, buzzing, clanging, beeping, and playing music at once. (Well, it is annoying to parents who have to go into the arcades and endure all the screeching and booming to retrieve their kids, but the games aren’t designed for them.)

计算机游戏经常使用声音来指示事件和情况。在游戏中,声音并不烦人;它是意料之中的。游戏中的使用非常普遍,即使在游戏厅中,几十台机器同时发出砰砰声、轰鸣声、嗡嗡声、哐当声、哔哔声和播放音乐。 (嗯,这对必须进入游戏厅并忍受所有尖叫声和轰鸣声来接孩子的父母来说很烦人,但游戏并不是为他们设计的。)

Method 3: wiggle or blink briefly

方法 3:短暂地抖动或闪烁

As described earlier in this chapter, our peripheral vision is good at detecting motion, and motion in the periphery causes reflexive eye movements that bring the motion into the fovea. User-interface designers can make use of this by wiggling or flashing messages briefly when they want to ensure that users see them. It does not take much motion to trigger eye movement toward it. Just a tiny bit of motion is enough to make a viewer’s eyes zip over in that direction. Millions of years of evolution have had quite an effect.

如本章前面所述,我们的周边视觉在检测运动方面表现良好,而周边的运动会引起反射性的眼球运动,将运动物体带到中央凹。用户界面设计师可以利用这一点,在需要确保用户看到消息时,短暂地晃动或闪烁消息。只需一点运动就能触发眼球朝向它移动。只需微小的运动就足以让观看者的眼睛迅速移向那个方向。数百万年的进化产生了相当大的影响。

As an example of using motion to attract users’ eye attention, Apple’s iCloud online service briefly shakes the entire dialogue box horizontally when a user enters an invalid username or password (see Fig. 5.14). In addition to clearly indicating “No” (like a person shaking his head), this attracts the users’ eyeballs, guaranteed. Because after all, the motion in the corner of your eye might be a leopard.

以运动吸引用户注意力的一个例子是,当用户输入无效的用户名或密码时,Apple 的 iCloud 在线服务会短暂地水平晃动整个对话框(见图 5.14)。除了明确地表示“不”(就像一个人摇着头一样),这还能吸引用户的注意力。毕竟,眼角的运动可能是一只豹子。

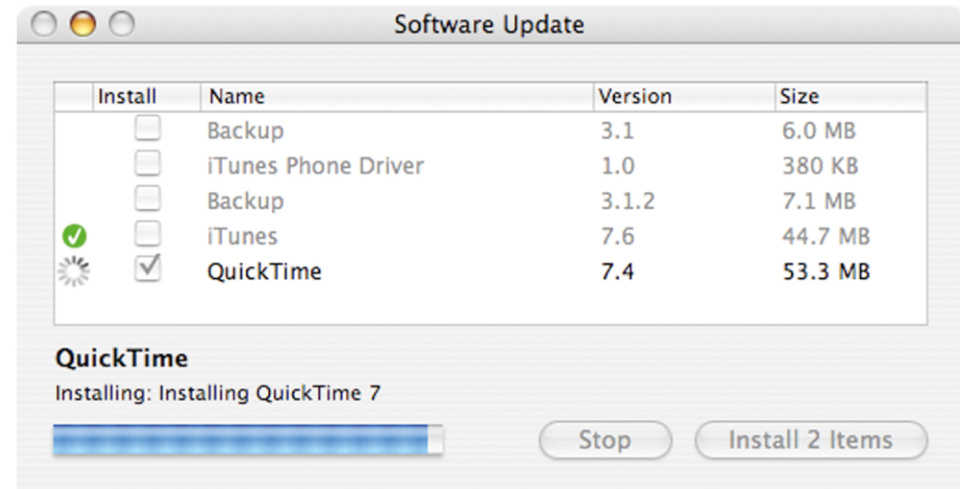

The most common use of blinking in computer user interfaces (other than advertisements) is in menu bars. When an action (e.g., Edit or Copy) is selected from a menu, it usually blinks once before the menu closes to confirm that the system “got” the command— that is, that the user didn’t miss the menu item. This use of blinking is very common. It is so quick that most computer users aren’t even aware of it, but if menu items didn’t blink once, we would have less confidence that we actually selected them.

计算机用户界面中最常见的闪烁用途(除广告外)是在菜单栏中。当从菜单中选择一个操作(例如,编辑或复制)时,它通常在菜单关闭之前闪烁一次,以确认系统“收到了”该命令——也就是说,用户没有错过菜单项。这种闪烁的使用非常普遍。它非常快,以至于大多数计算机用户甚至没有意识到它的存在,但如果菜单项不闪烁一次,我们就不会那么确信自己确实选择了它们。

Motion and blinking, like pop-up dialogue boxes and beeping, must be used sparingly. Most experienced computer users consider wiggling, blinking objects on-screen to be annoying. Most of us have learned to ignore displays that blink because many such displays are advertisements. Conversely, a few computer users have attentional impairments that make it difficult for them to ignore something blinking or wiggling.

动画和闪烁,就像弹出对话框和哔哔声一样,必须谨慎使用。大多数有经验的计算机用户认为屏幕上闪烁、晃动的物体很烦人。我们大多数人已经学会了忽略闪烁的显示器,因为许多这样的显示器都是广告。相反,一些计算机用户有注意力障碍,这使得他们难以忽略闪烁或晃动的东西。

FIGURE 5.14Apple’s iCloud shakes the dialogue box briefly on login errors to attract a user’s fovea toward it.

图 5.14 苹果的 iCloud 在登录错误时短暂地晃动对话框,以吸引用户的中央视觉区域注意到它。

Therefore, if wiggling or blinking is used, it should be brief—it should last about a quarter- to a half-second, no longer. Otherwise, it quickly goes from an unconscious attention-grabber to a conscious annoyance.

因此,如果使用晃动或闪烁,应该简短——大约持续四分之一到半秒,不能更长。否则,它会迅速从无意识的注意力吸引者变成有意识的烦扰。

Use heavy-artillery methods sparingly to avoid habituating your users

应谨慎使用重型武器方法,以避免用户习惯化

There is one final reason to use the preceding heavy-artillery methods sparingly (i.e., only for critical messages): to avoid habituating your users. When pop-ups, sound, motion, and blinking are used too often to attract users’ attention, a psychological phenomenon called habituation sets in (see Chapter 1). Our brain pays less and less attention to any stimulus that occurs frequently.

还有最后一个原因要谨慎使用前面提到的重炮方法(即,仅用于关键信息):避免让你的用户习惯化。当弹窗、声音、动画和闪烁过于频繁地用来吸引用户的注意力时,就会产生一种心理现象,称为习惯化(见第一章)。我们的大脑对频繁出现的任何刺激的关注会越来越少。

It is like the old fable of the boy who cried “Wolf!” too often. Eventually, the villagers learned to ignore his cries, so when a wolf actually did come, his cries went unheeded. Overuse of strong attention-getting methods can cause important messages to be blocked by habituation.

这就像古老的“狼来了”寓言。如果男孩喊“狼来了”的次数太多,最终村民们学会了忽视他的喊叫,所以当狼真的来了时,他的喊叫无人理会。过度使用强烈的注意力吸引方法会导致重要信息因习惯化而被屏蔽。

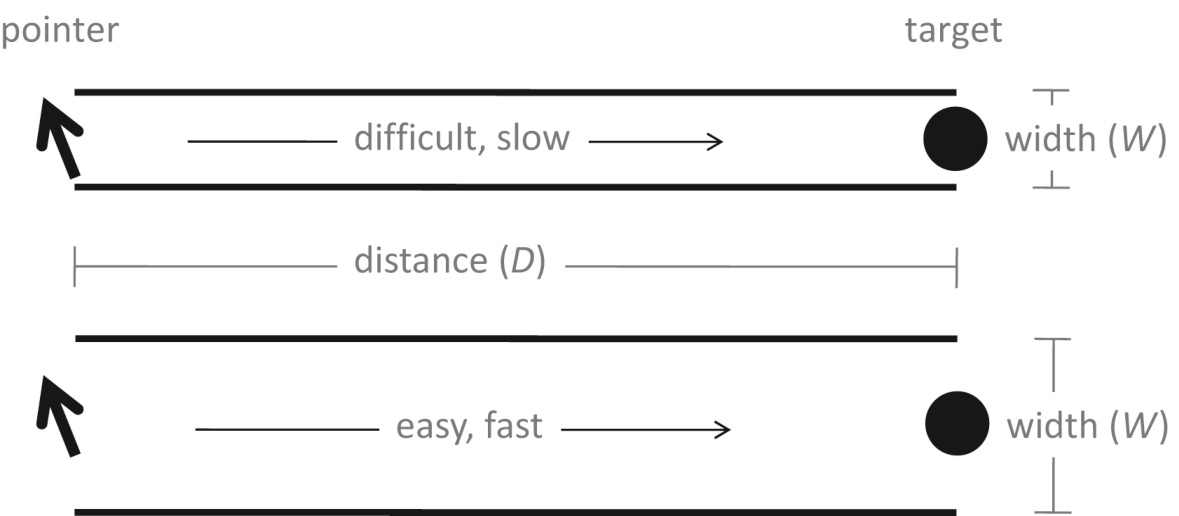

Visual Search is Linear Unless Targets “Pop” in the Periphery

视觉搜索是线性的,除非目标在周边“弹出”

As explained earlier, one function of peripheral vision is to drive our eyes to focus the fovea on important things—those that match our goals or that might be a threat. For example, objects moving in our peripheral vision fairly reliably “pull” our eyes and attention toward them. Similarly, fuzzy, blurred images related to our current goals also attract our attention. This is why our perception—in this case our visual perception—is biased by our goals (see Chapter 1).

如前所述,周边视觉的一个功能是驱动我们的眼睛将焦点对准重要的事物——那些符合我们的目标或可能构成威胁的事物。例如,我们周边视觉中移动的物体相当可靠地“吸引”我们的眼睛和注意力朝向它们。同样,与我们的当前目标相关的模糊、模糊的图像也会吸引我们的注意力。这就是为什么我们的感知——在这种情况下是我们的视觉感知——会受到我们目标的影响(参见第一章)。

FIGURE 5.15 Finding the Z requires scanning carefully through the characters.

图 5.15 寻找 Z 需要仔细扫描这些字符。

Peripheral vision is a crucial component in visual search despite its low spatial and color resolution. When we are looking for an object, our entire visual system, including the periphery, primes itself to detect that object. It does so by sensitizing neural networks running from the retina to the visual cortex of the brain. The neural networks are sensitized to detect features of the sought object (Treisman and Gelade, 1980; Wolfe, 1994; Wolfe and Gray, 2007).

尽管空间和颜色分辨率较低,但周边视觉是视觉搜索的一个关键组成部分。当我们寻找一个物体时,我们整个视觉系统,包括周边视觉,都会自行准备检测该物体。它通过使从视网膜到大脑视觉皮层的神经网络的敏感性得到提高来实现这一点。这些神经网络被敏化以检测所寻物体的特征(Treisman 和 Gelade,1980 年;Wolfe,1994 年;Wolfe 和 Gray,2007 年)。

However, how helpful the periphery is in aiding visual search depends strongly on the identifying features of the sought object and how distinct those features are from the features of other objects in our visual field. Look quickly at Fig. 5.15 and find the Z.

然而,周边视觉在辅助视觉搜索中的帮助程度,很大程度上取决于所寻目标对象的识别特征,以及这些特征与视野中其他对象特征的差异程度。快速看一下图 5.15,找到字母 Z。

To find the

要找到

Now look quickly at Fig. 5.16 and find the bold character.

现在快速看一下图 5.16,找到粗体字符。

That was much easier (i.e., faster), wasn’t it? You did not have to scan your fovea carefully through all the characters. Your periphery quickly detected the boldness and determined its location, and because that is what you were seeking, your visual system moved your fovea there. Your periphery could not determine exactly what was bold—that is beyond its resolution and abilities—but it did locate the boldness. In vision-researcher lingo, the periphery was primed to look for boldness in parallel over its entire area, and boldness is a distinctive feature of the target, so searching for a bold target is nonlinear. In designer lingo, we say that boldness “pops” in the periphery, assuming that only the target is bold.

那样就简单多了(也就是说更快了),不是吗?你不必仔细扫描你的中央凹。你的周边视觉很快检测到加粗并确定其位置,因为那正是你在寻找的,你的视觉系统将你的中央凹移到了那里。你的周边视觉无法精确确定什么是加粗——那就是它的分辨率和能力所不及的——但它确实找到了加粗。在视觉研究者的行话中,周边视觉已经准备好在整个区域并行地寻找加粗,而加粗是目标的一个显著特征,所以寻找一个加粗的目标是非线性的。在设计师的行话中,我们说加粗在周边视觉中“跳”出来,假设只有目标是加粗的。

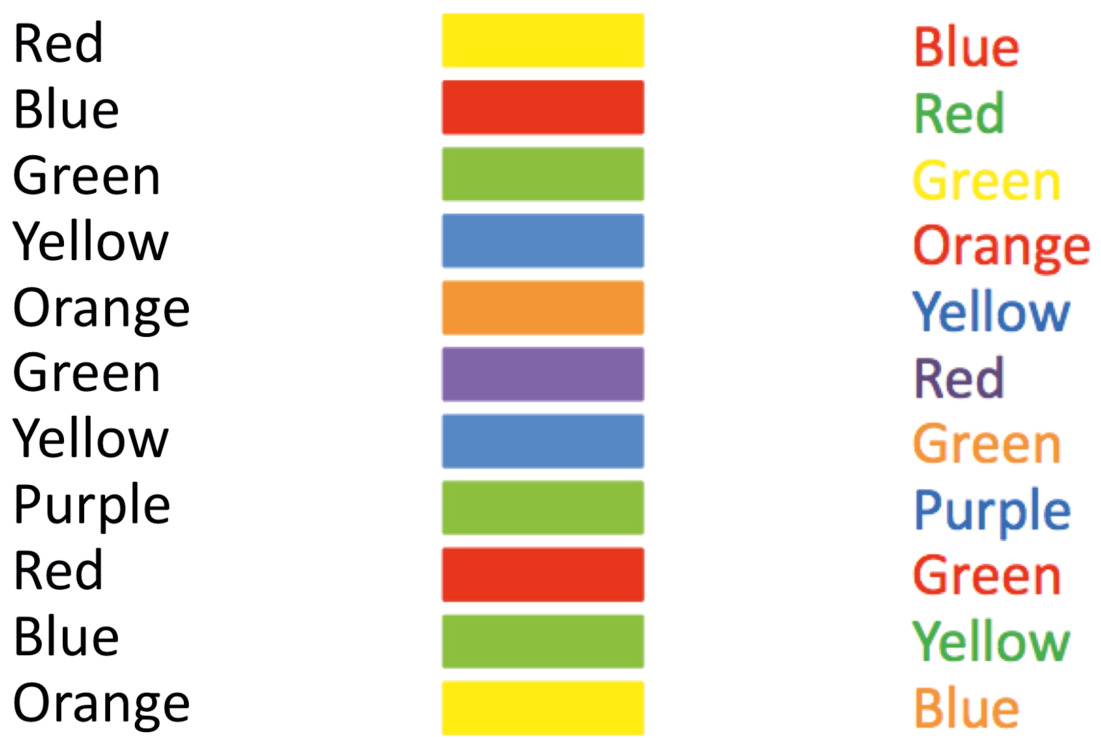

Color “pops” even more strongly. Compare counting the L’s in Fig. 5.17 with counting the red characters in Fig. 5.18.

颜色“跳”得更加明显。比较在图 5.17 中数 L 和在图 5.18 中数红色字符。

FIGURE 5.16 Finding the bold letter does not require scanning through everything.

图 5.16 找到加粗字母不需要扫描所有内容。

FIGURE 5.17 Counting L’s is hard—letter shape doesn’t “pop” among characters.

图 5.17 数 L 很困难——字母形状在字符中不“跳”出来。

FIGURE 5.18 Counting red characters is easy because color “pops.”

计算红色字符很容易,因为颜色“突出”。

What else makes things “pop” in the periphery? As described earlier, the periphery easily detects motion, so motion “pops.”

还有什么能让事物在周边“突出”?如前所述,周边很容易检测到运动,所以运动“突出”。

Generalizing from boldness, we also can say that font weight “pops,” because if all but one of the characters on a display were bold, the nonbold character would stand out. In general, a visual target will “pop out” in your periphery if it differs from surrounding objects in features that the low-resolution peripheral vision can detect. The more distinctive the features of the target, the more it “pops,” assuming the periphery can detect those features.

从粗体中推广,我们也可以说字体粗细“突出”,因为如果显示器上的所有字符除了一个都是粗体,那么非粗体字符就会突出。一般来说,如果目标在低分辨率的周边视觉可以检测到的特征上与周围物体不同,那么视觉目标会在你的周边“突出”。目标特征越独特,它就越“突出”,假设周边可以检测到这些特征。

Using peripheral “pop” in design

在设计中使用周边“弹出”

Designers use peripheral “pop” to focus the attention of a product’s users as well as to allow users to find information faster. Chapter 3 described how visual hierarchy—titles, headings, boldness, bullets, and indenting—can make it easier for users to spot and extract the information they need from text. Glance back at Fig. 3.7B in Chapter 3 and see how the headings and bullets make the topics and subtopics “pop” so readers can go right to them.

设计师利用周边“突出”来吸引产品用户的注意力,以及让用户更快地找到信息。第三章描述了如何通过视觉层次——标题、副标题、粗体、项目符号和缩进——使用户更容易从文本中找到并提取他们需要的信息。回顾一下第三章中的图 3.7B,看看标题和项目符号如何使主题和子主题“突出”,以便读者可以直接找到它们。

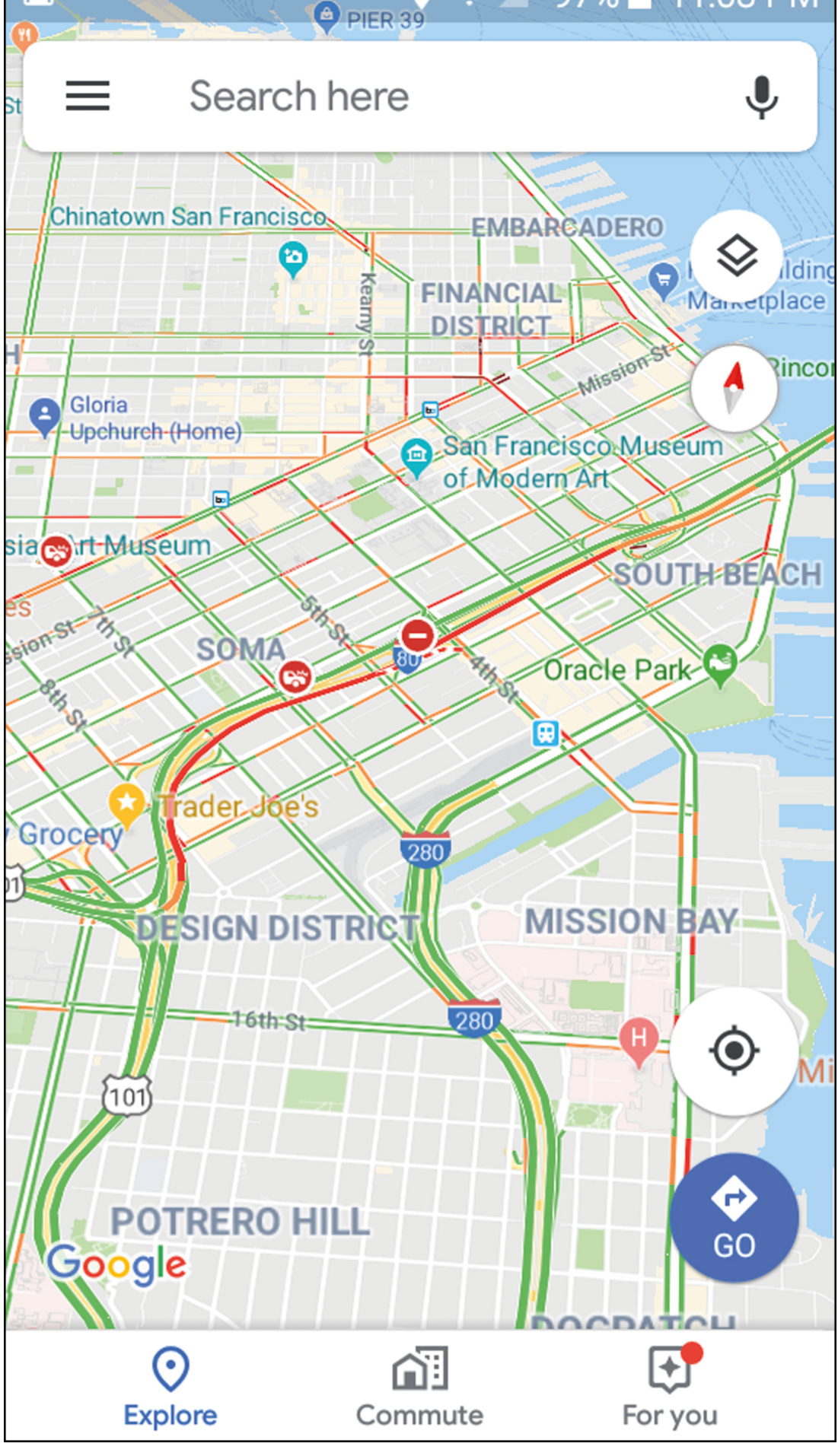

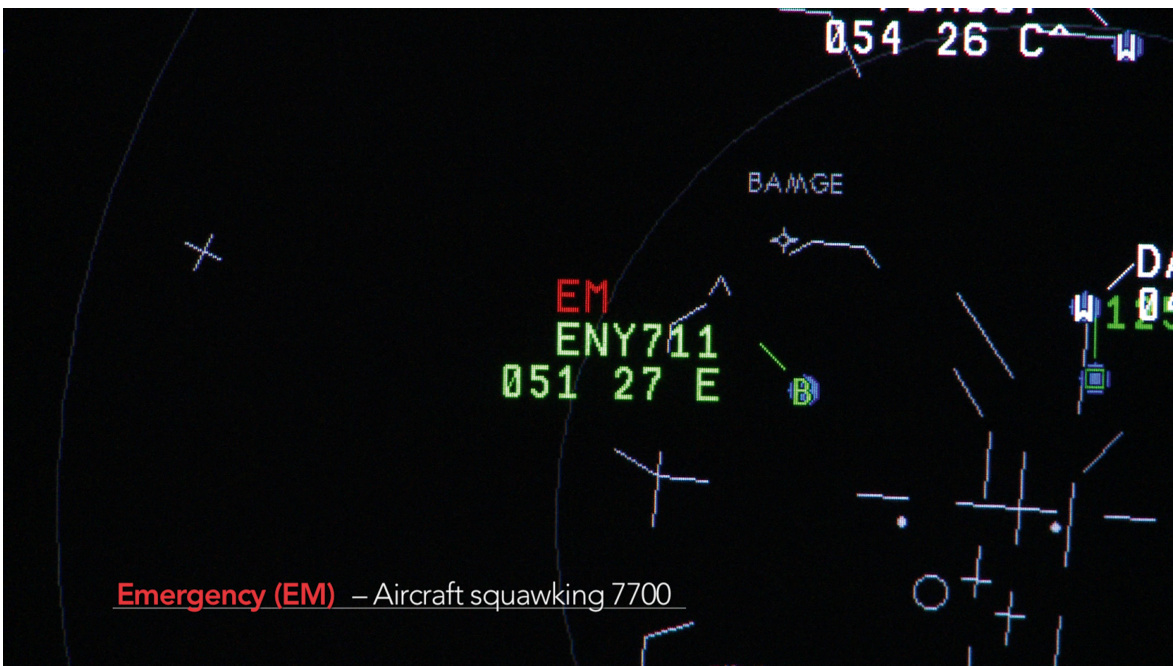

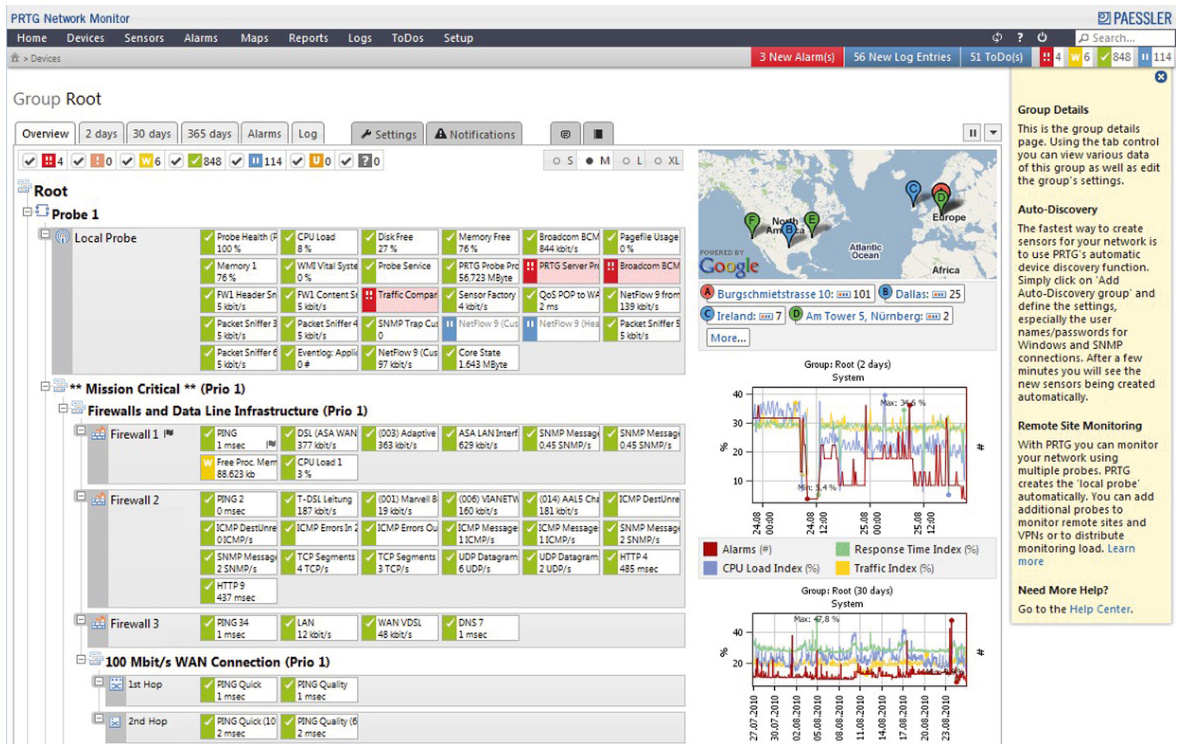

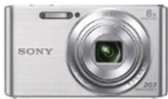

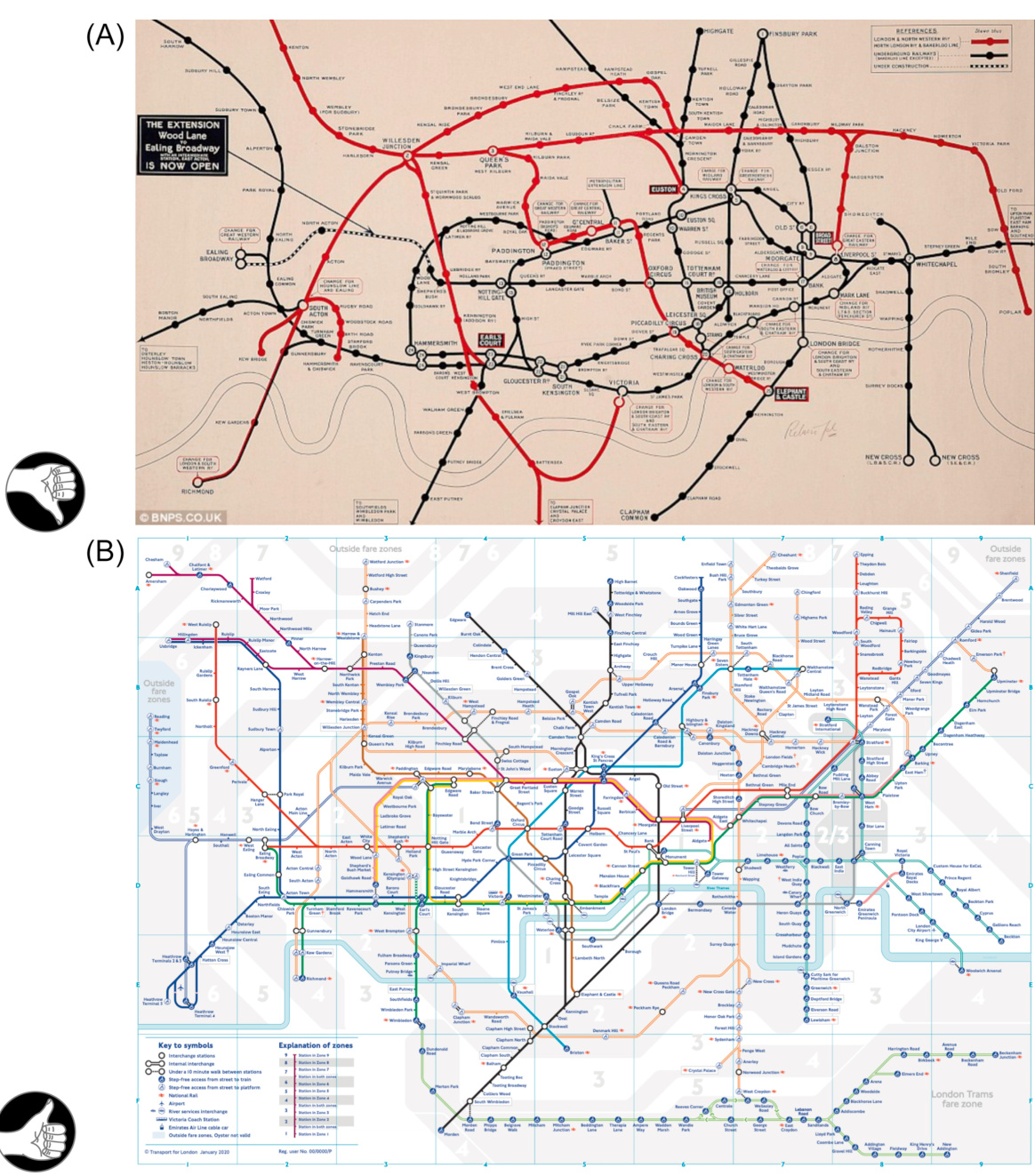

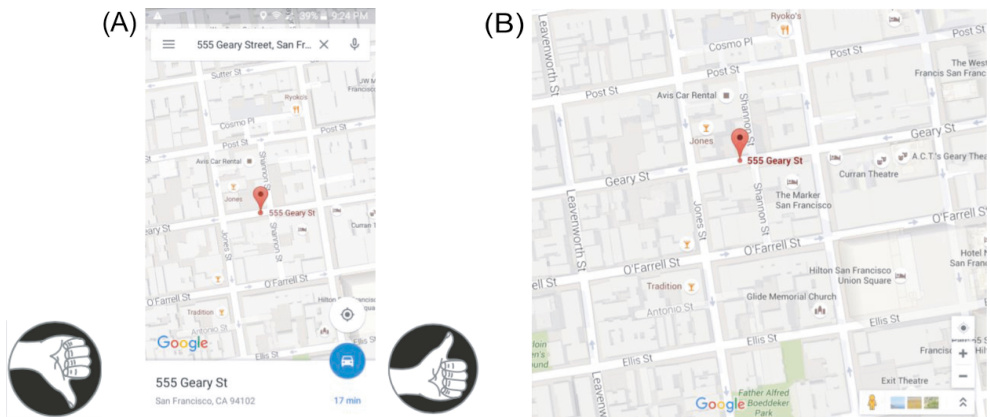

Many interactive systems use color to indicate status, usually reserving red for problems. Online maps and most vehicle GPS devices mark traffic jams with red so they stand out (see Fig. 5.19). Systems for controlling air traffic mark potential collisions in red (see Fig. 5.20). Applications for monitoring servers and networks use color to show the health status of assets or groups of them (see Fig. 5.21).

许多交互式系统使用颜色来指示状态,通常将红色保留用于问题。在线地图和大多数车辆 GPS 设备用红色标记交通拥堵,以便突出显示(见图 5.19)。空中交通控制系统用红色标记潜在的碰撞(见图 5.20)。用于监控服务器和网络的应用程序使用颜色来显示资产或资产组的健康状况(见图 5.21)。

FIGURE 5.19 Google Maps uses color to show traffic conditions. Red indicates traffic jams.

图 5.19 Google 地图使用颜色显示交通状况。红色表示交通拥堵。

FIGURE 5.20Air traffic control systems often use red to make potential collisions “pop” out.

图 5.20 空中交通管制系统通常使用红色使潜在的碰撞“突出”。

FIGURE 5.21Paessler’s monitoring tool uses color to show the health of network components.

图 5.21 Paessler 的监控工具使用颜色显示网络组件的健康状况。

These are all uses of peripheral “pop” to make important information stand out and visual search nonlinear.

这些都是使用“弹出”效果来突出重要信息,并使视觉搜索非线性的用法。

When there are many possible targets

当有多个可能的目标时

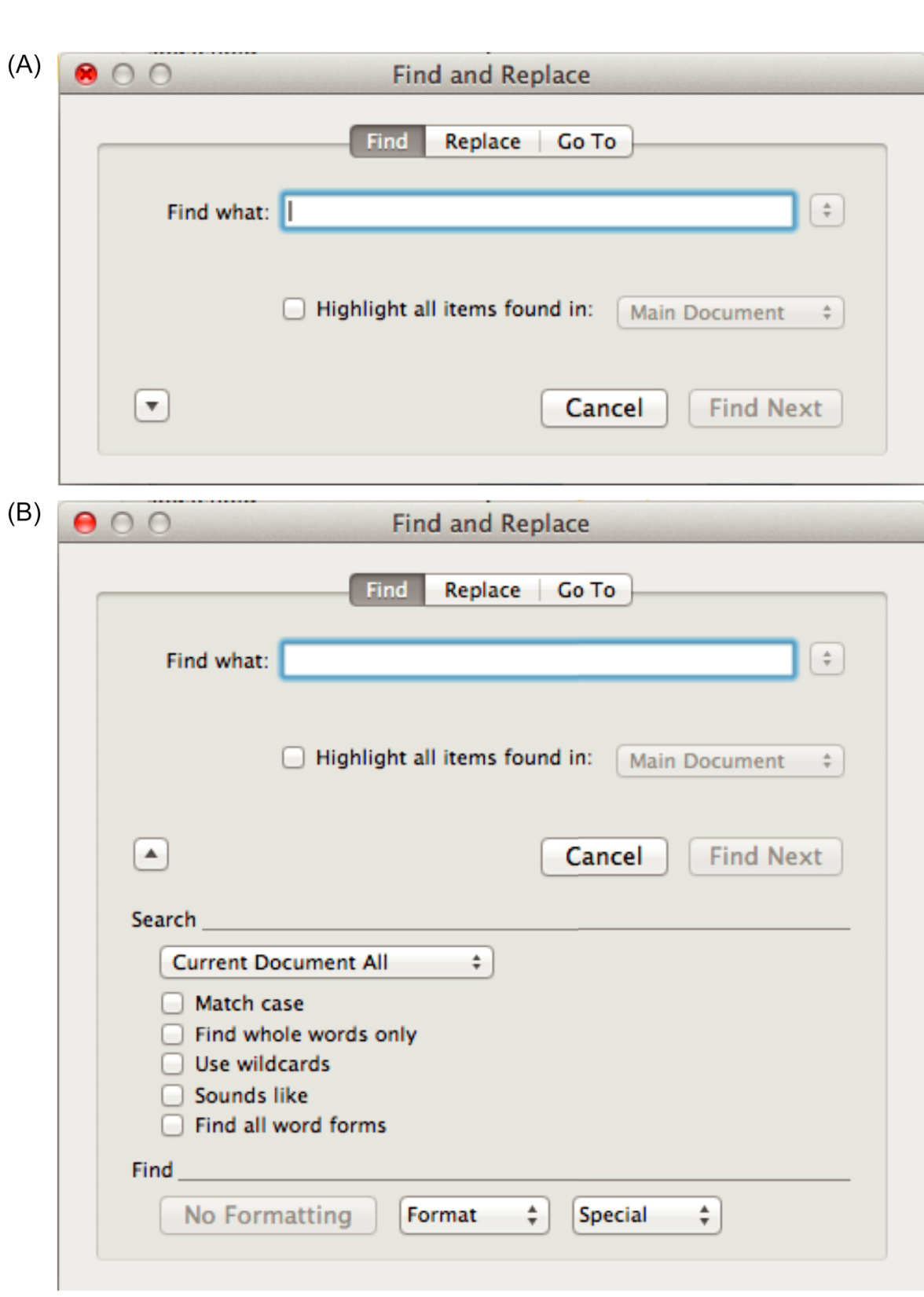

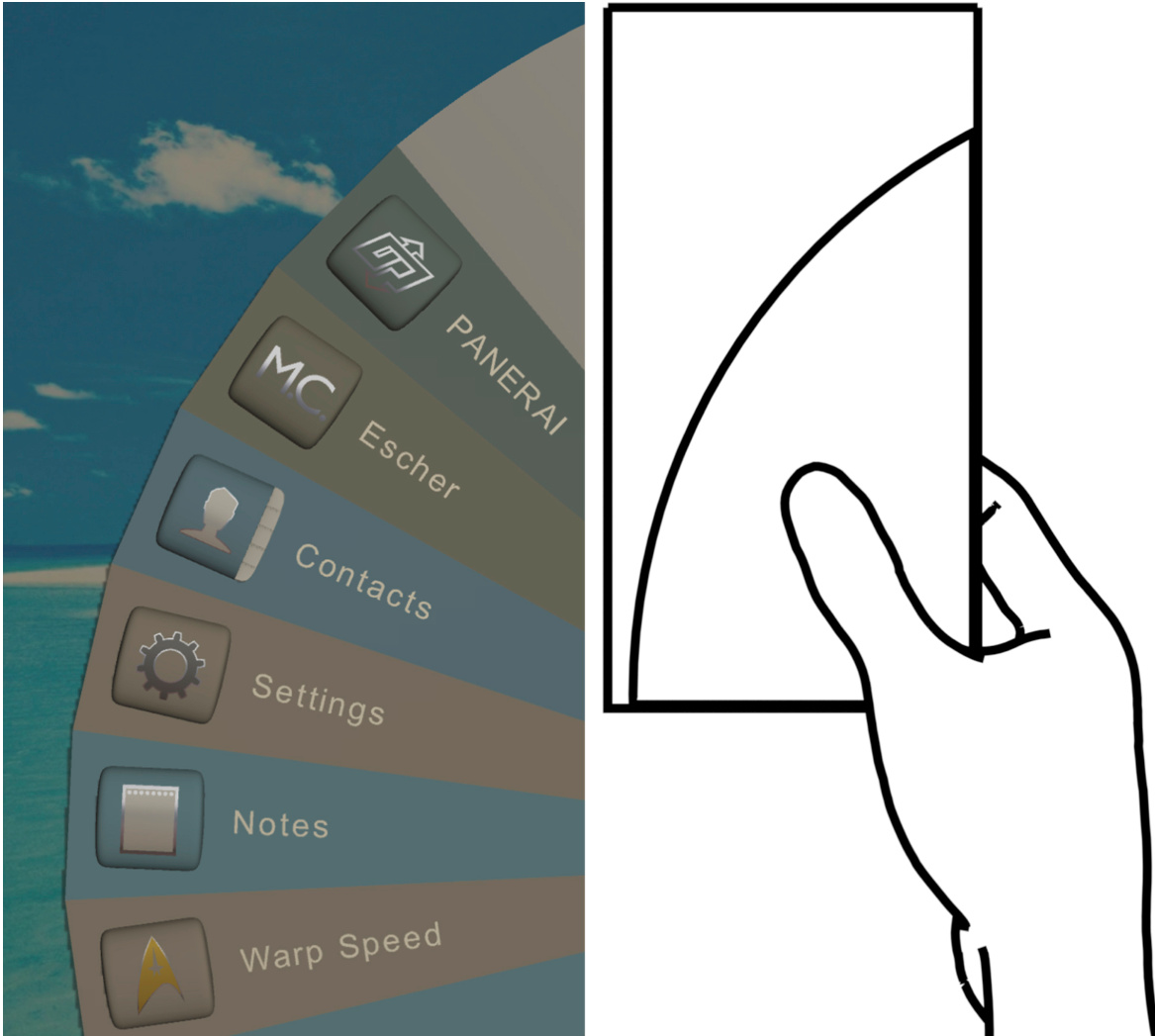

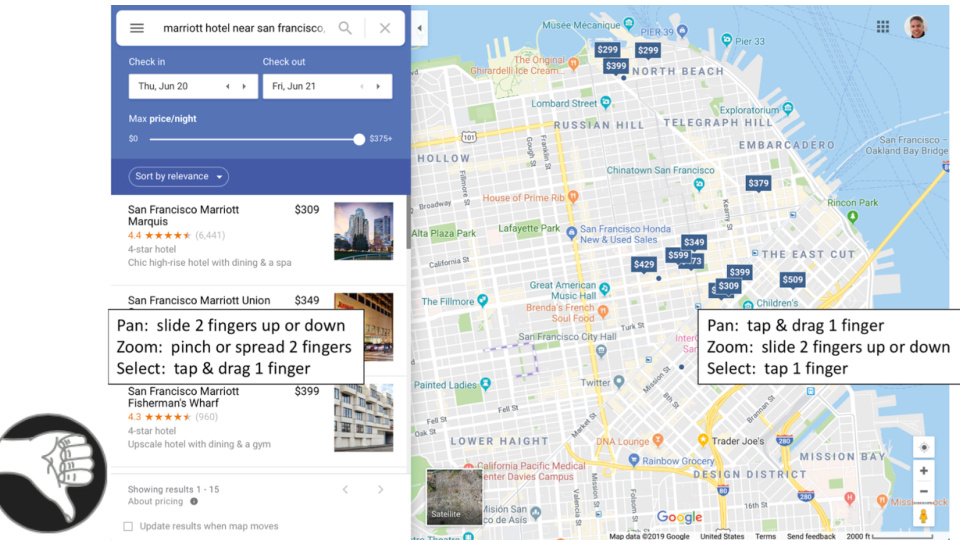

Sometimes in displays of many items, any of them could be what the user wants. Examples include command menus (see Fig. 5.22A) and app pallets (see Fig. 5.22B). Assume that the application cannot anticipate which item or items a user is likely to want and highlight them. That is a fair assumption for today’s applications. 5 Are users doomed to have to search linearly through such displays for the item they want?

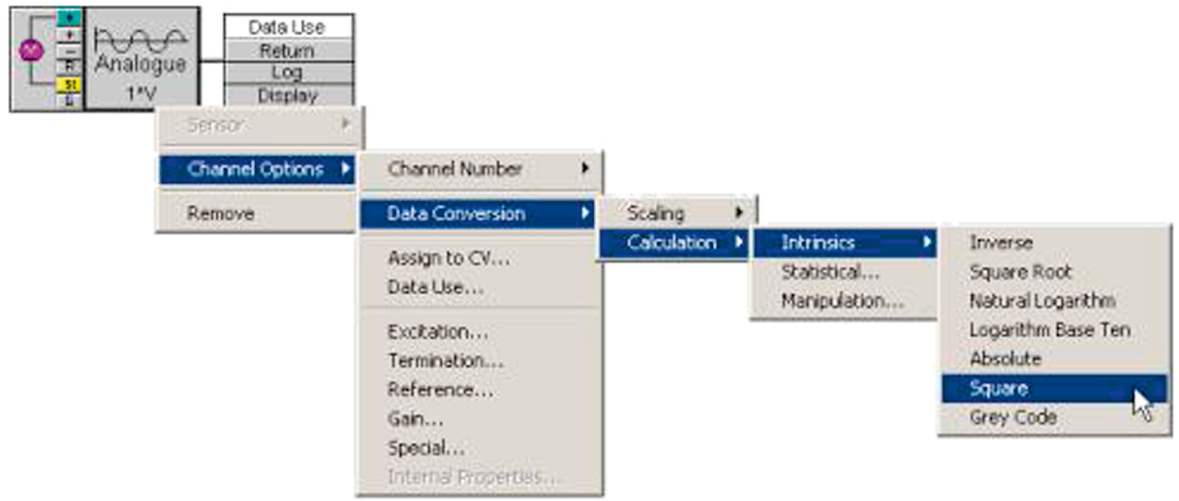

在显示许多项目时,任何一个都可能是用户想要的项目。例如命令菜单(见图 5.22A)和应用程序面板(见图 5.22B)。假设应用程序无法预知用户可能想要哪个项目或哪些项目并突出显示它们。这对于当今的应用程序来说是一个合理的假设。5 用户是否注定要在这种显示中线性地搜索他们想要的项目?

| Tools Table Window Spelling and Grammar工具表窗口拼写和语法 |

| Thesaurus... >;#R Hyphenation... Smart Lookup... >;#L Language...同义词库... >;#R 断言... 智能查找... >;#L 语言... |

| Word Count... AutoCorrect...自动更正...字数统计... |

| Check Accessibility检查可访问性 |

| Track Changes Combine Documents...跟踪修订合并文档... |

| Block Authors Unblock All My Blocked Areas Protect Document...屏蔽作者解除所有屏蔽区域保护文档... |

| Envelopes... Labels...信封...标签... |

| Macro Templates and Add-ins... Customize Keyboard...宏模板和插件...自定义键盘... |

That depends. Designers can try to make each item so distinctive that when a specific one is the user’s target, the user’s peripheral vision will spot it among all the other items. Designing distinctive sets of icons is hard—especially when the set is large—but it can be done (see Johnson et al., 1989). Designing sets of icons so distinctive that they can be distinguished in peripheral vision is very hard, but not impossible. For example, if a user goes to the macOS application pallet to open his or her calendar, a white rectangular blob in the periphery with something black in the middle is more likely to attract the user’s eye than a blue circular blob (see Fig. 5.22B). The trick is to not get too fancy and detailed with the icons—give each a distinctive color and gross shape.

这取决于。设计师可以尝试让每个项目都足够独特,以至于当用户的目标是特定项目时,用户的周边视觉能在所有其他项目中识别出它。设计独特的一组图标很困难——尤其是当这组很大时——但它可以完成(参见 Johnson 等人,1989 年)。设计一组能在周边视觉中区分的图标非常困难,但并非不可能。例如,如果用户去 macOS 应用程序面板打开他们的日历,一个在周边视觉中呈白色矩形块,中间有黑色东西,比一个蓝色圆形块更有可能吸引用户的眼睛(参见图 5.22B)。诀窍是不要让图标太花哨和详细——给每个图标一个独特的颜色和大致形状。

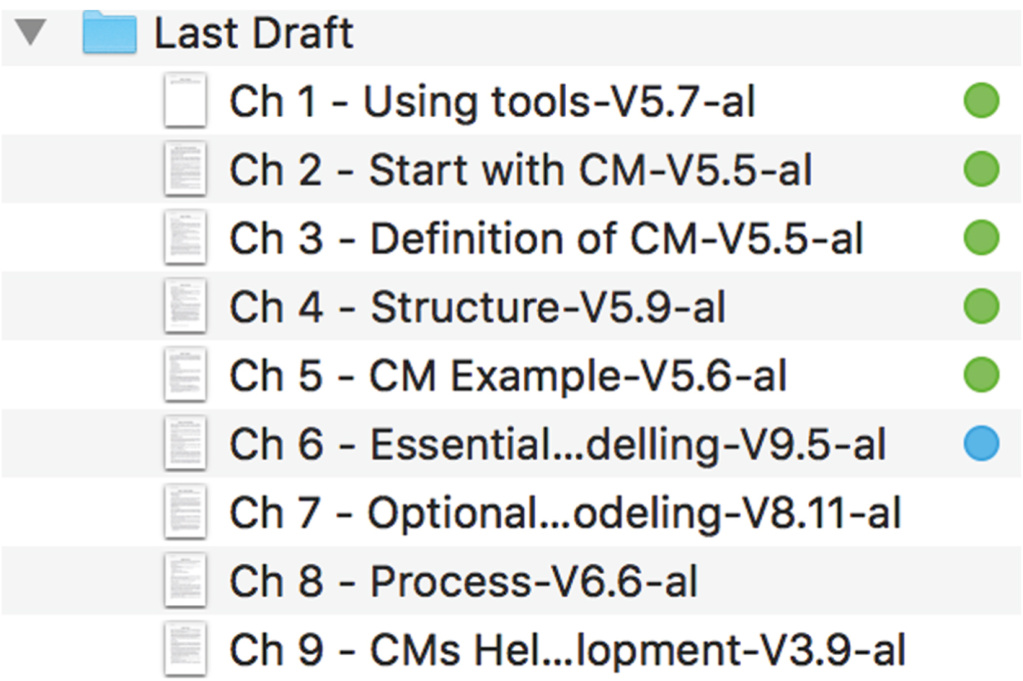

On the other hand, if the potential targets are all words, as in command menus (see Fig. 5.22A), visual distinctiveness is not an option. In textual menus and lists, visual search will be linear, at least at first. With practice, users learn the positions of frequently used items in menus, lists, and pallets, so searching for particular items is no longer linear.

另一方面,如果潜在目标都是单词,例如在命令菜单(见图 5.22A)中,视觉区分度不是一个选项。在文本菜单和列表中,视觉搜索将是线性的,至少一开始是这样。通过练习,用户学会了菜单、列表和调色板中常用项目的位置,因此查找特定项目不再是线性的。

That is why applications should never move items around in menus, lists, or pallets. Doing that prevents users from learning item positions, thereby dooming them to search linearly forever. Therefore, the use of “dynamic menus” is considered a major userinterface design mistake (Johnson, 2007).

正是如此,应用程序绝不应该在菜单、列表或面板中移动项目。这样做会阻止用户学习项目位置,从而注定他们永远线性搜索。因此,使用“动态菜单”被认为是主要的用户界面设计错误(约翰逊,2007 年)。

Important Takeaways

重要要点

• Unlike digital cameras, the resolution of human vision is much higher in a small area in the middle of our visual field than it is everywhere else. The small area is called the fovea, and it makes up only about

• 与数码相机不同,人类视觉在视野中央的小区域内的分辨率远高于其他地方。这个小区域称为中央凹,它只占我们视野的约

• Peripheral vision guides our eyes and attention toward bjects and events that either match our goals or represent possible threats. Peripheral vision can detect motion and ends to move our eyes toward whatever is moving even hough it cannot identify what is moving. eripheral vision is good in low-light situations. ome visual features “pop out” in peripheral vision, and ome do not. Font weight pops. Color pops. Motion pops. etter shape does not pop.

• 周边视觉引导我们的眼睛和注意力朝向符合我们的目标或代表可能威胁的物体和事件。周边视觉可以检测运动,并使我们的眼睛朝向移动的东西,即使它无法识别正在移动的是什么。周边视觉在低光情况下表现良好。一些视觉特征在周边视觉中会“突出”,而另一些则不会。字体粗细会突出。颜色会突出。运动会突出。形状不会突出。

• Designing based on the strengths and weaknesses of eripheral vision: • Place new, important, or changed information where users will be looking—in or near where their fovea is positioned. Information placed elsewhere may not be noticed. • Use color, motion, a distinctive shape, etc. to make important information “pop” in peripheral vision to attract users’ fovea and attention. Red is commonly used to attract attention to error messages. • Overuse of any stimulus causes people to habituate to it, diminishing its ability to attract attention. Pop-up messages can in principle force users to attend to them, but they are often overused, and therefore many experienced users of digital technology have learned to ignore them. • Sound can attract a user’s attention, but it can also be annoying, especially in environments shared with other people.

• 基于周边视觉的优势和劣势进行设计:• 将新的、重要的或更改的信息放置在用户注视的位置——即他们的黄斑所在位置。放置在其他位置的信息可能不会被注意到。• 使用颜色、运动、独特的形状等,使重要信息在周边视觉中“突出”,以吸引用户的黄斑和注意力。红色通常用于吸引对错误消息的注意。• 过度使用任何刺激会导致人们习惯于它,从而降低其吸引注意力的能力。弹窗消息原则上可以迫使用户注意它们,但它们通常被过度使用,因此许多有经验的数字技术用户已经学会了忽略它们。• 声音可以吸引用户的注意力,但它也可能令人烦恼,尤其是在与他人共享的环境中。

1Our brains also fill in perceptual gaps that occur during rapid (saccadic) eye movements, when vision is suppressed (see Chapter 14).

1我们的大脑也会填补快速(扫视)眼动期间出现的感知间隙,此时视觉被抑制(见第 14 章)。

4Although this example is old, it is still the best example of this issue I have found.

4尽管这个例子很旧,但它仍然是我找到的最佳例子。

5But in the not-too-distant future it might not be.

5但在不久的将来,情况可能就不是这样了。

Chapter 6: Reading is Unnatural

第六章:阅读是不自然的

Abstract

摘要

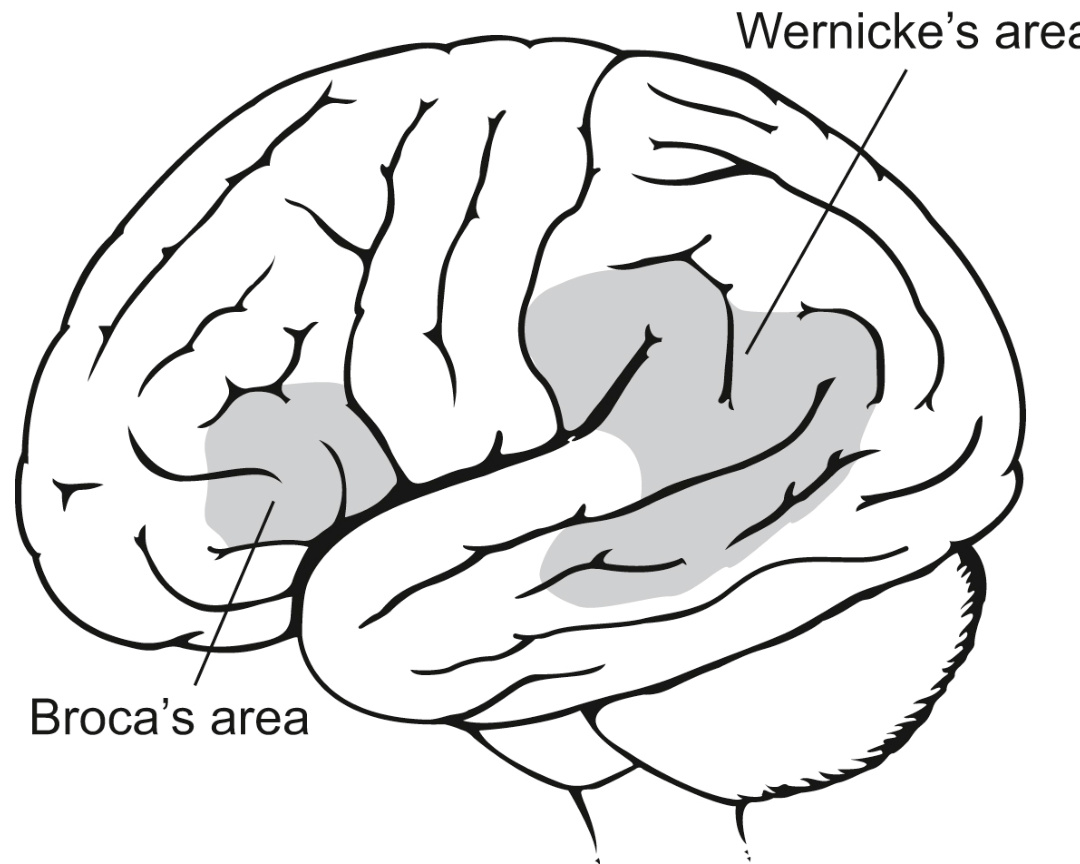

Humans are “prewired” to learn a spoken language but not to learn to read. This chapter reviews current research findings on how people read and learn to read, including how our eyes move as we read, how reading is primarily a function of fovea vision with a little help from peripheral vision, and whether reading is mainly a top-down or bottom-up process. It then shows that poor display of information can disrupt reading and that many user interfaces can be improved by reducing the reading required.

人类天生就适合学习口语,但不适合学习阅读。本章回顾了关于人们如何阅读和学习阅读的当前研究成果,包括阅读时眼睛的运动方式,阅读主要是 fovea 视觉功能,并辅以一点周边视觉,以及阅读主要是自上而下还是自下而上的过程。然后,它表明信息的展示不佳会干扰阅读,并且许多用户界面可以通过减少阅读量来改进。

Keywords

关键词

Background; Bottom-up; Broca’s area; Context; Contrast; Font size; Fovea; Jargon; Language; Patterns; Perifovea; Reading; Saccade; Temporal lobe; Top-down; Typefaces; Vocabulary; Wernicke’s area; Word frequency